Murder on Säntis

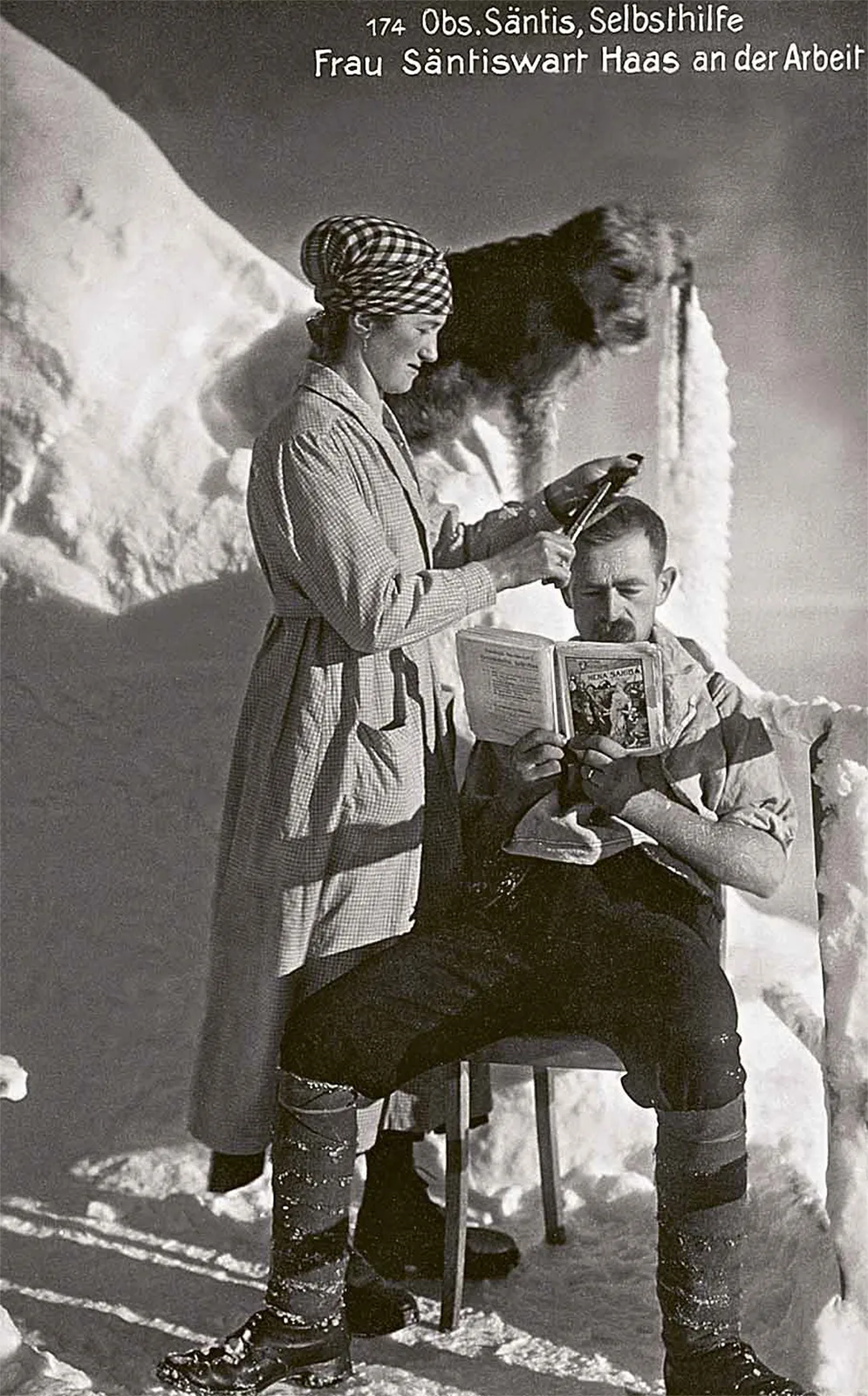

In February 1922, the operator of the Säntis weather station and his wife became victims of a crime. New findings are shining a light on the dark story behind this crime that caused widespread consternation.

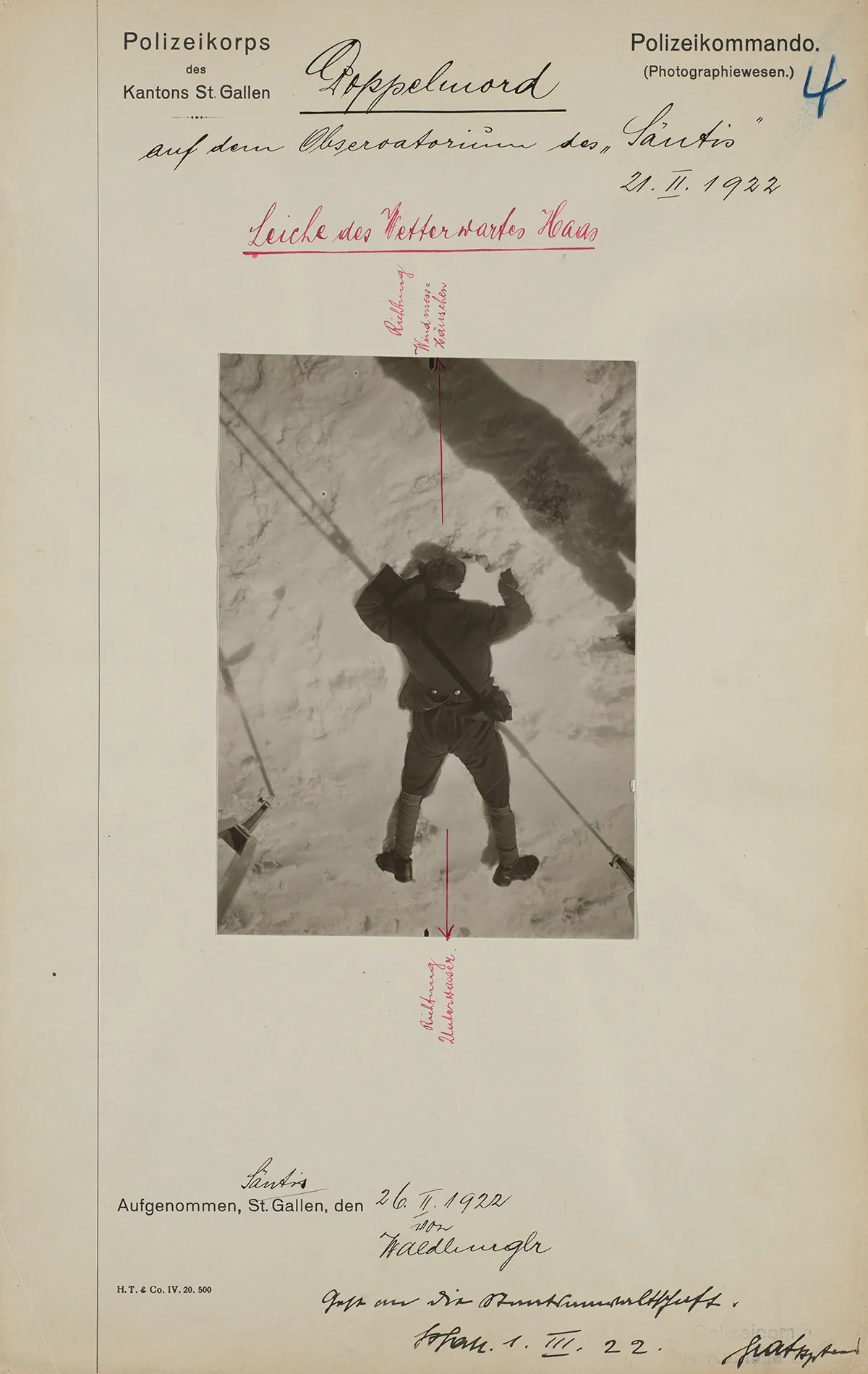

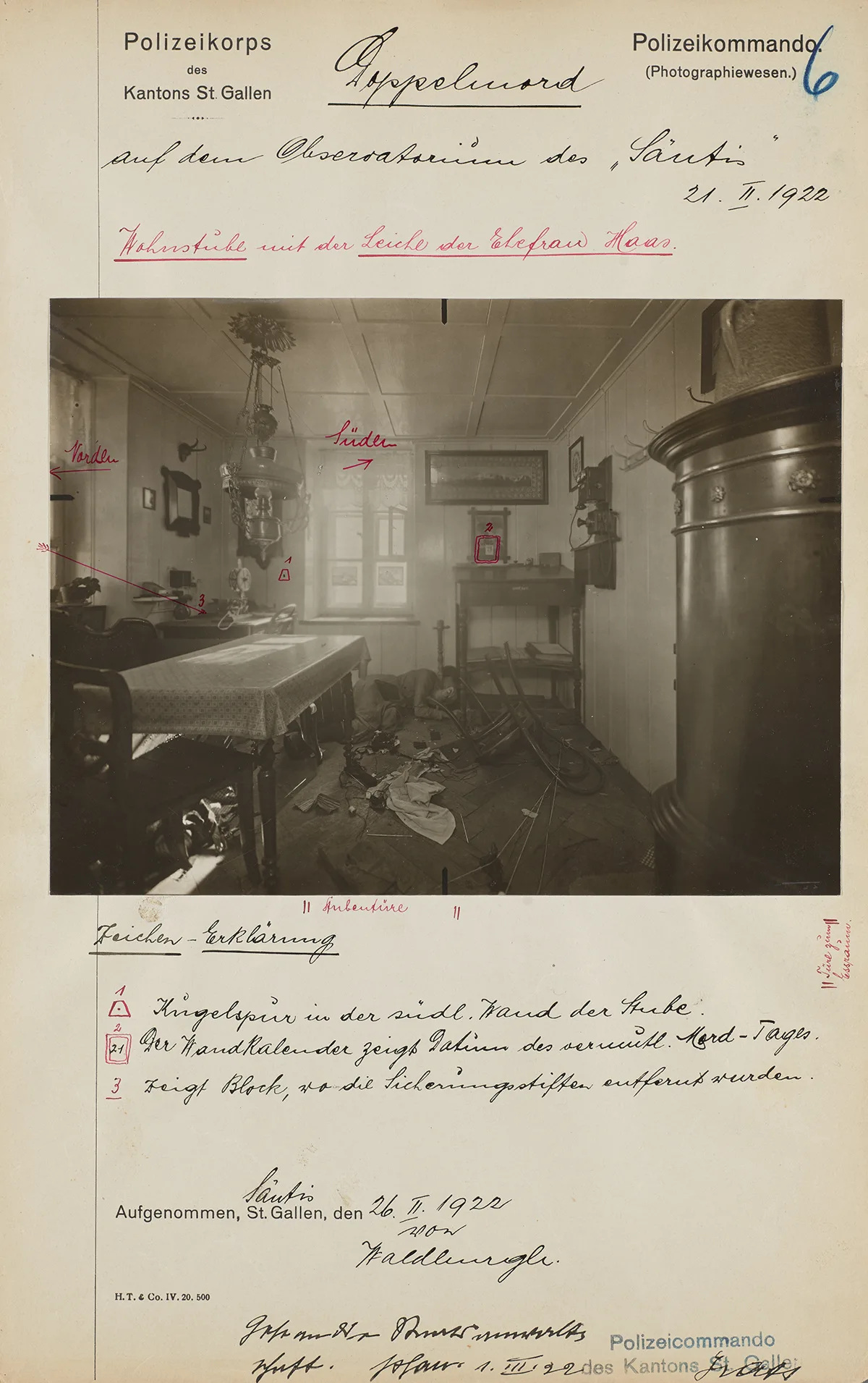

The door to the room was locked and the three men had to break it open. A dreadful sight met their eyes: next to the standing desk by the window lay the lifeless body of Magdalena Haas in a pool of blood. The room had been completely destroyed. Suspecting foul play, the three went in search of Heinrich. They climbed up to the second storey and, from there, passed through the tunnel that led to the summit plateau. There, they found Heinrich’s corpse lying face down.

The police concluded that the chaotic state of the office was not the result of a fight but rather the work of Storm, the family’s dog. The animal must have gone almost mad after being shut in the room without food or water for four days. Magdalena had also been shot at close range. The first bullet had missed her and smashed into the wall; the second hit her in the chest, killing her.

The murder weapon was identified by the bullets as a Browning pistol. Dumdum bullets were used, which act like an exploding grenade when entering the body and, in the event the victim survives, increase their suffering. These can only be obtained illegally or by tampering with and filing the ends of legally obtained ammunition. The tear-off calendar showed 21 February, thus confirming the day of the double murder.

The victims and perpetrator knew each other

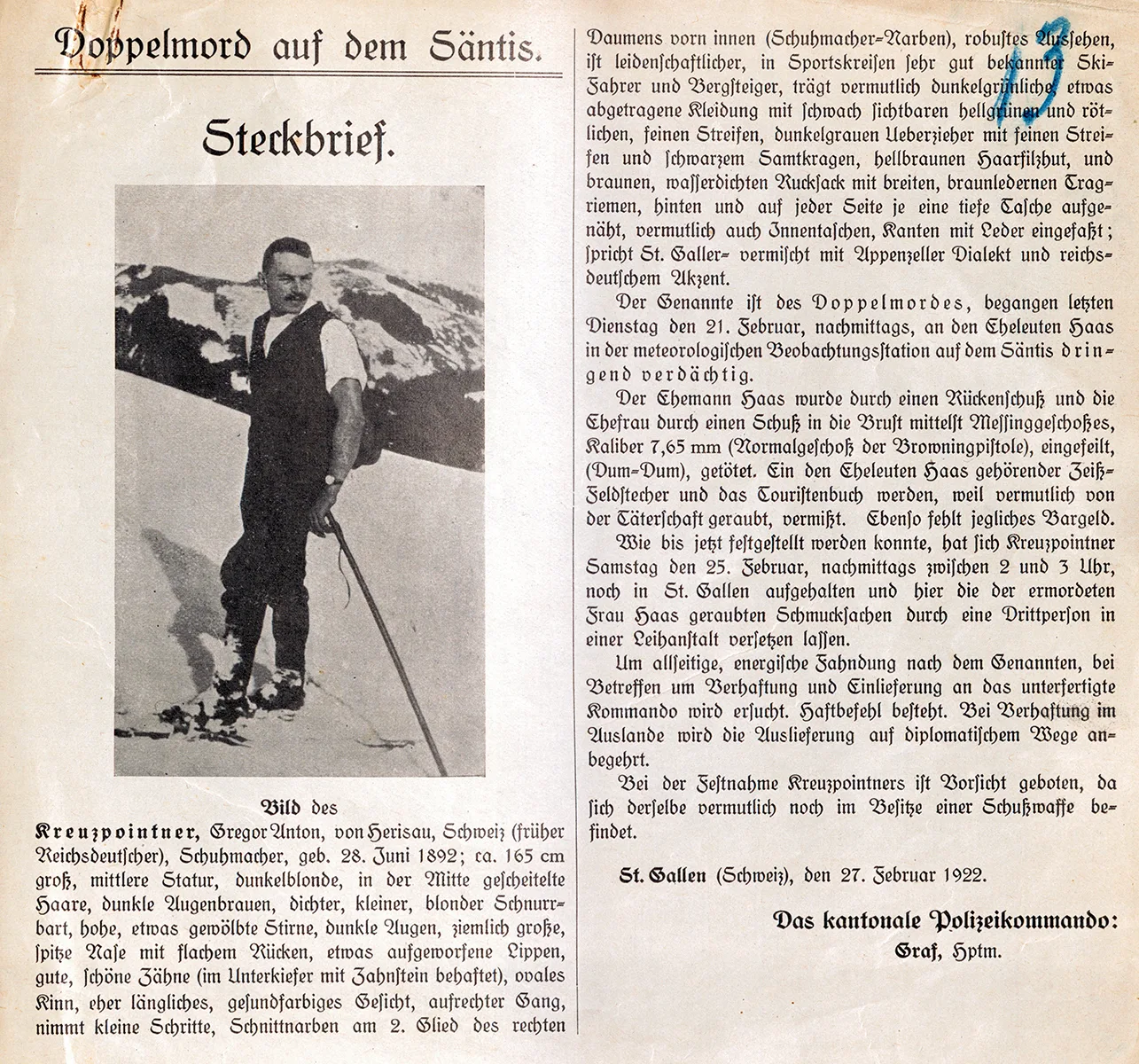

On 26 February, a wanted notice was issued giving the double murderer’s name, description and photo. In the four days before the corpses were discovered, Kreuzpointner would have had enough time to make his escape. Yet he stayed in the region and was spotted on a number of occasions, as was later evident. Since nobody was as yet aware of his crime, nobody reported him to the police. He moved Magdalena’s jewellery to another location and handed the weapon under mysterious circumstances to a third party, who then passed it to the police.

To die for…

The history to this tragedy begins in 1919, when the former weather station operator, who had lived on the mountain with his wife for 30 years, retired. There had been a simple guest house – ironically nicknamed the Grand Hotel Thörig by the first visitors – on Säntis since 1846. From 1882 onwards, one of its rooms was used as a weather station. From 1887, the weather station operator was able to use the stone building specially constructed for this purpose.

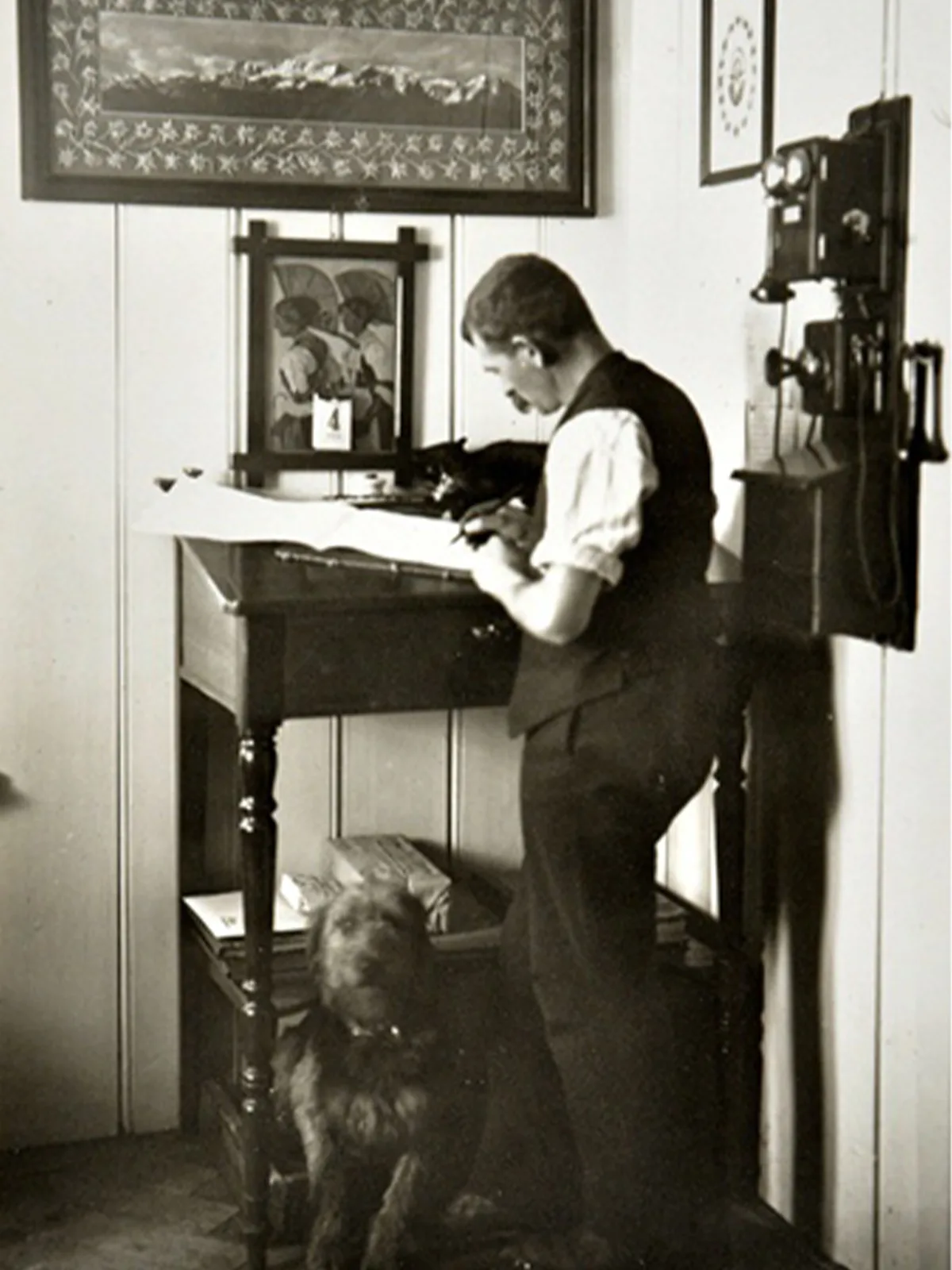

Over 50 applicants were said to have applied for the unusual post. Born in Appenzell and a keen alpinist, Heinrich Haas stood head and shoulders above the competition. He had actually trained as a baker, but at that time was working as a conductor in Zurich. The 33-year-old was accepted for the post, thereby obtaining his dream job. On climbing Säntis for the first time he even exclaimed with enthusiasm: “The view up there is to die for.”

Bertha later described her stepmother as modest, kind-hearted and someone who liked order. She spoke of her father as a supporter, advisor and philanthropist who had always been cheerful and kind. The couple had a happy marriage and led a life largely free of conflict. Heinrich was an enthusiastic amateur photographer and documented life on the mountain with a wealth of photographs. These also included glass plate stereoscopic images.

A passionate climber and skier, he often visited the mountains in his free time. Most members of the SAC Säntis alpine skiing club were gentry, yet they welcomed this sporty, lower-class newcomer. Evidently, he could be very engaging. There are also less flattering characterisations of him, however. A fellow mountaineer described him as outspoken, “self-centred and cold”. Kreuzpointner was once claimed to have said that inexperienced mountaineers who got into trouble shouldn’t be helped but rather “left to die a miserable death”.

When, on 31 July 1914, the German Emperor declared a state of war, Kreuzpointner immediately applied for naturalization to avoid being conscripted, and quickly received his Swiss passport. In February 1919, he moved within the half-canton of Ausserrhoden to Trogen, where he opened a cobbler’s workshop. After failing to obtain the post of Säntis weather station operator, in December 1919 he moved to the city of St Gallen, where he tried a second time to set up an independent shoemaking business. The specialist in climbing shoes and ski boots was declared bankrupt in December 1921 on account of earlier debts. He nonetheless found a job as a cobbler at a shoe shop in Romanshorn, which he started on 30 January 1922. However, he threw in the towel after just one week.

On the morning of 21 February, Magdalena telephoned again to say that, given the good weather, Kreuzpointner had eventually got ready to leave. This was the last sign of life from the summit. The contents of the stomach and intestines during the post-mortem showed that Magdalena had been killed no more than two hours after lunch and Heinrich half an hour or one hour earlier.

Since Kreuzpointner had a pistol on him, his plan from the start had been to shoot them. He appears to have held them responsible for his failure to obtain the post of Säntis weather station operator that he had so coveted, and which was also very well remunerated. He makes no mention of the act in his short farewell letter to his girlfriend.

Macabre back and forth over the corpses

At the time, there was disagreement between the experts over cantonal responsibility for the crime: the borders of the Canton of St Gallen and the two half-cantons of Appenzell Ausserrhoden and Appenzell Innerrhoden meet at the summit of Säntis. The body of Magdalena Haas was clearly found on Innerrhoden territory, since the weather station is situated squarely within this. Heinrich’s body, however, lay in an area for which the border between St Gallen and Innerrhoden was drawn too imprecisely on the map for it to be clearly assigned. For this reason, the police and anatomical investigative work was divided between Innerrhoden and St Gallen.

Kreuzpointner’s body was found in the Ausserrhoden municipality of Urnäsch. Despite this, he was denied a grave in the cemetery there because this would have led to “the cemetery being desecrated”. Herisau, where he was a citizen, and the city of St Gallen, where he was last registered, were likewise unwilling to have the evildoer on their soil or land. In doing so, all three violated the Federal Constitution. According to this, it is the authorities’ responsibility to ensure that “every deceased person is able to be buried as is fitting”. The corpse was sent to the Institute of Anatomy at the University of Zurich for research purposes. All three municipalities paid for its transport there.

Kreuzpointner’s body was found in the Ausserrhoden municipality of Urnäsch. Despite this, he was denied a grave in the cemetery there because this would have led to “the cemetery being desecrated”. Herisau, where he was a citizen, and the city of St Gallen, where he was last registered, were likewise unwilling to have the evildoer on their soil or land. In doing so, all three violated the Federal Constitution. According to this, it is the authorities’ responsibility to ensure that “every deceased person is able to be buried as is fitting”. The corpse was sent to the Institute of Anatomy at the University of Zurich for research purposes. All three municipalities paid for its transport there.

“We cannot understand it,

we don’t want to believe it

and just keep asking ourselves

how could this happen?

It could almost rip away our

faith in the Lord above!

Why, O Creator,

would You permit this crime to be committed?”

This outpouring of sympathy also extended to the couple’s two orphaned daughters. Many donated to a fund-raising campaign and this, in addition to the financial support from the survivors’ insurance, ensured that the two girls were well provided for afterwards. Both girls were assigned a guardian who would safeguard their interests until they reached maturity. Initially, they both stayed with relatives, and subsequently with foster parents. The files even mention the whereabouts of the dog, Storm: he was taken in by Heinrich’s brother.

This article appeared in the Bieler Tagblatt. It was published in that newspaper on 19 February 2022 under the title “The view up there is to die for”.