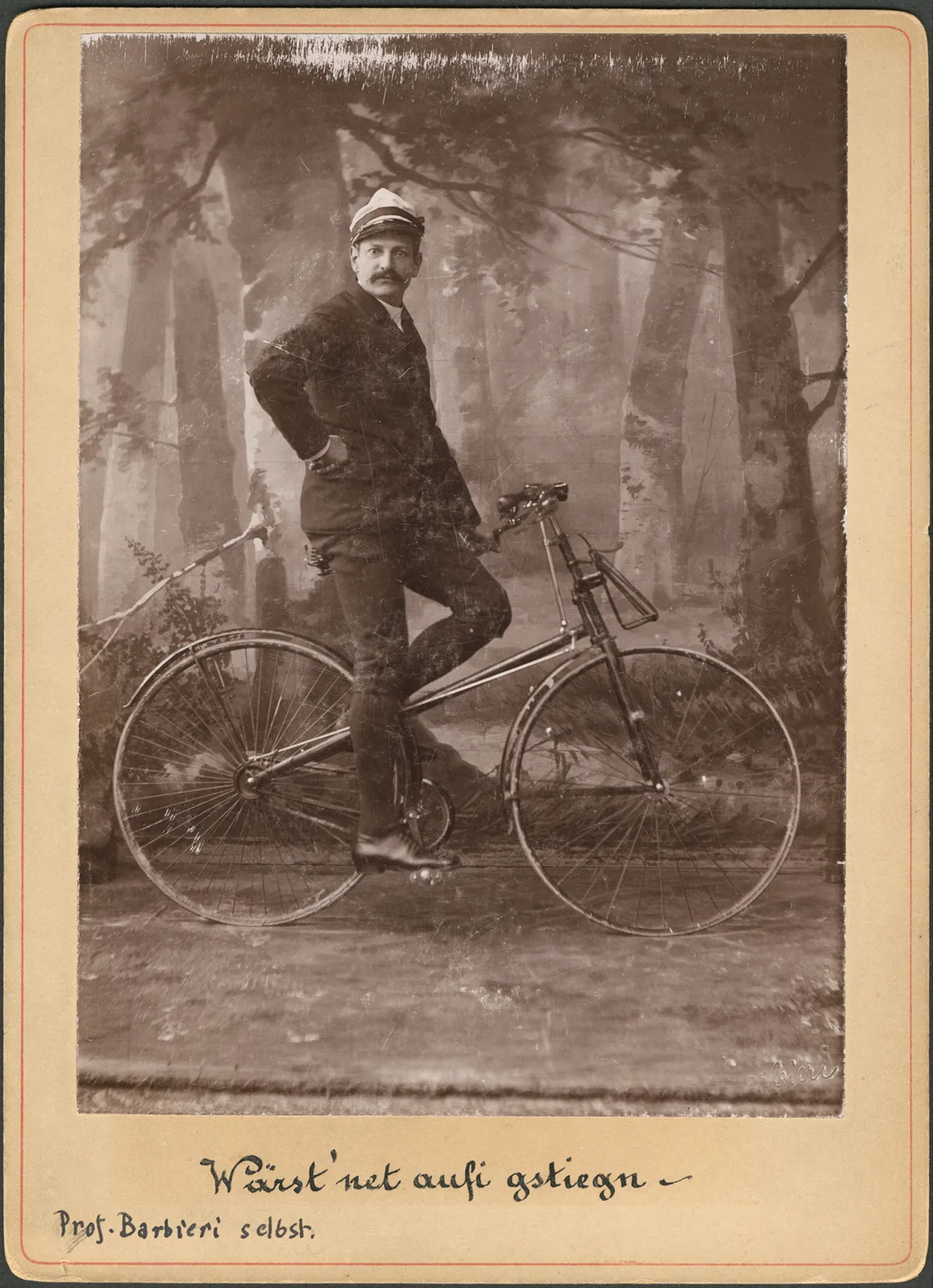

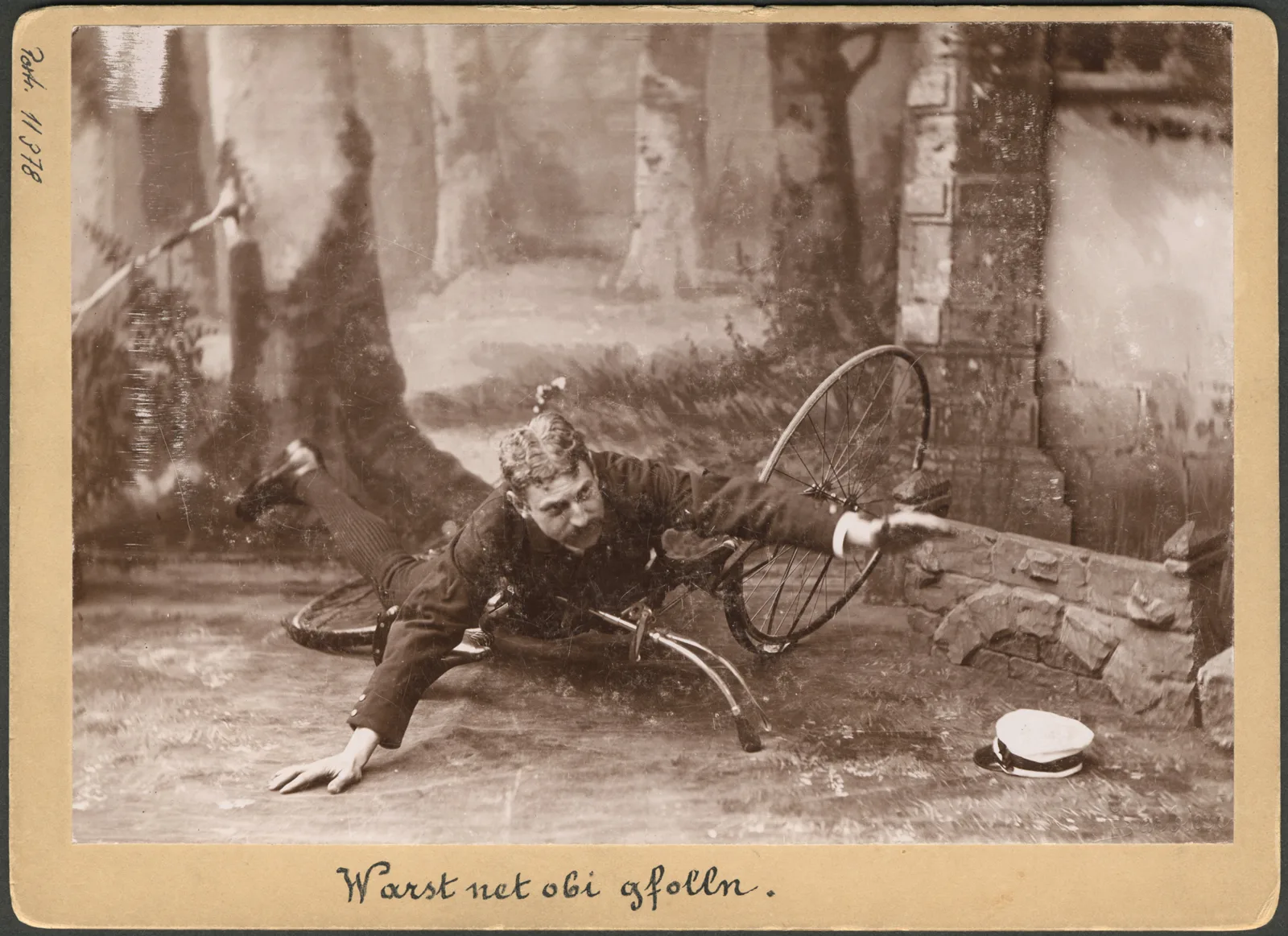

When the bicycle was the public’s darling

Cycling is booming, thanks to coronavirus and e-bikes. But the height of the cycling craze was in the early decades of the 20th century. Back then, the bicycle ruled the streets, and in fact in 1913 the view in the Federal Parliament was that: “The world today would not be able to manage without the bicycle.”

Extensively used in day-to-day life

Enormous social radiance

The battle for legislative regulation

Cycle associations capable of launching referendums

Promoting cycling is now a constitutional mandate