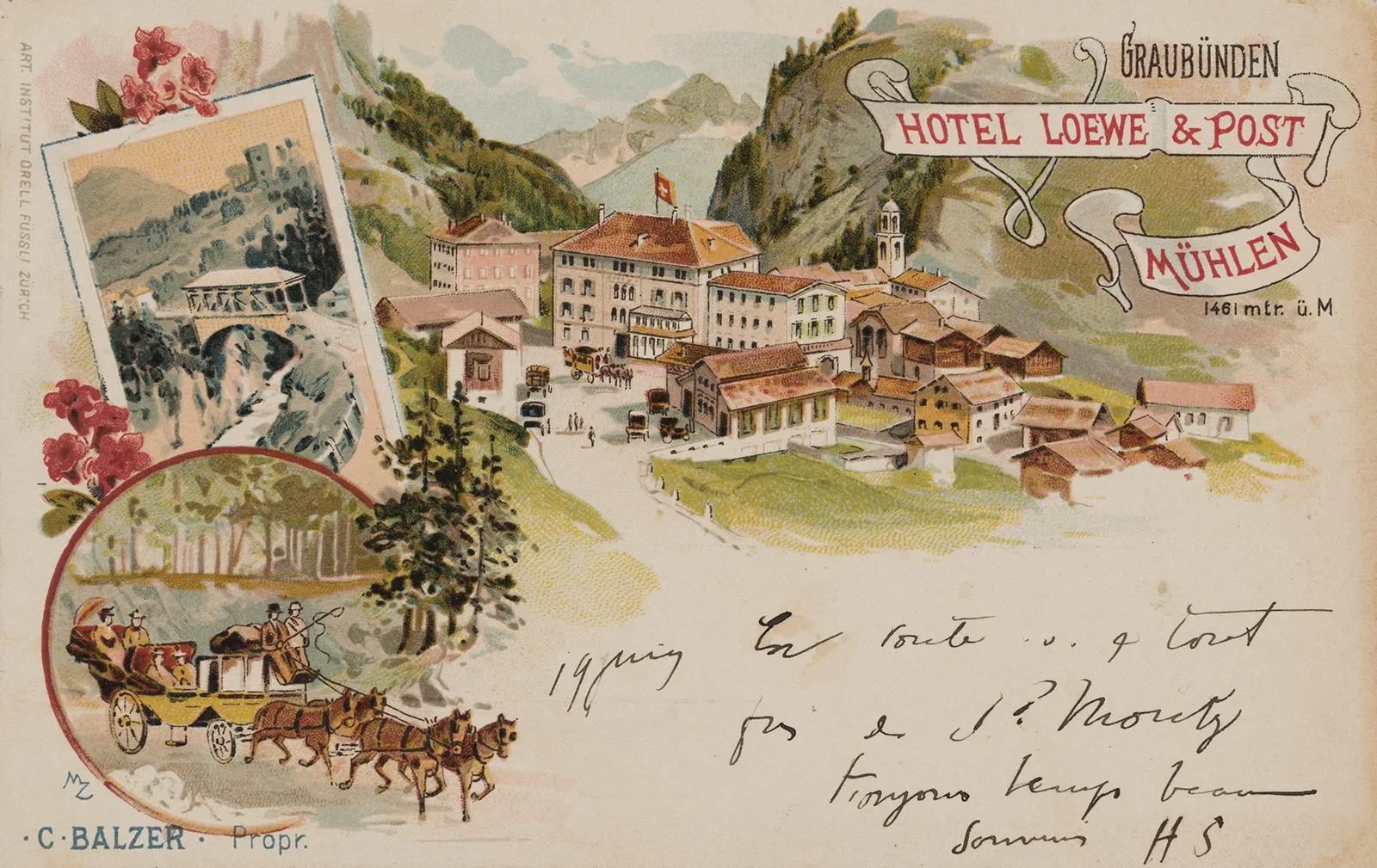

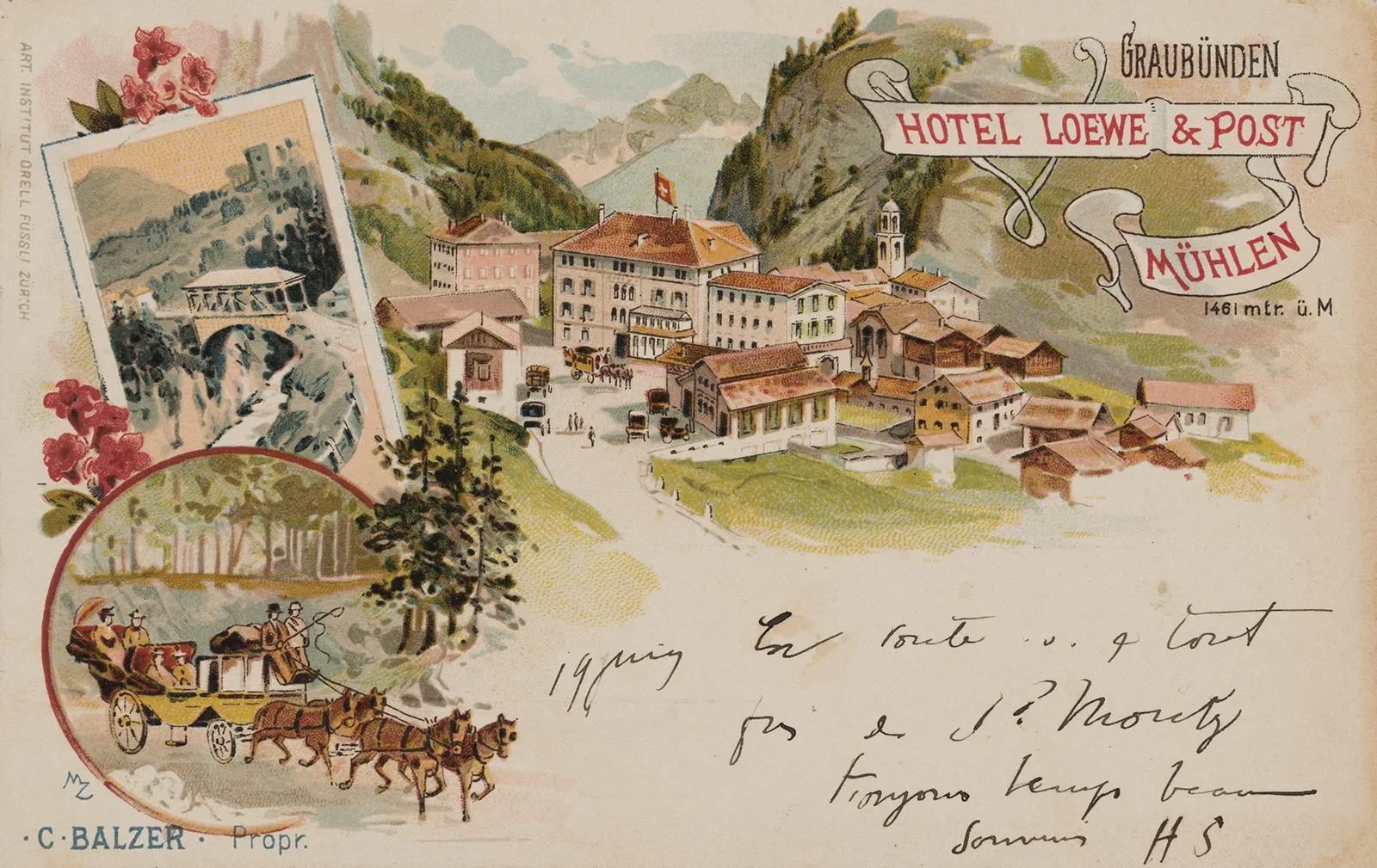

Emmanuel Schmid: coachman to the social elite during the Belle Époque

Coachman Emmanuel Schmid from Graubünden regularly drove his famous passenger Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen around the Alps in the late 19th century.

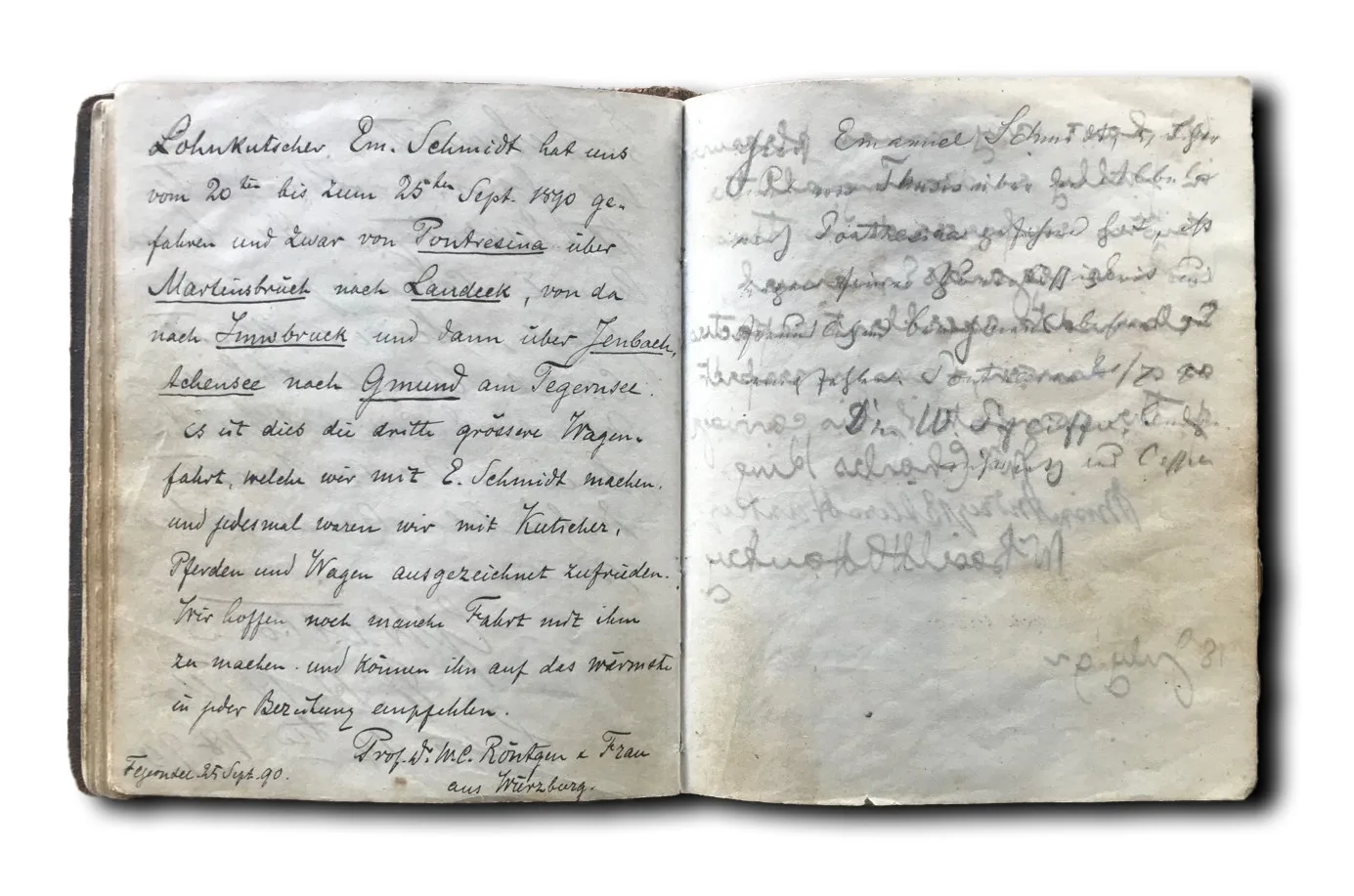

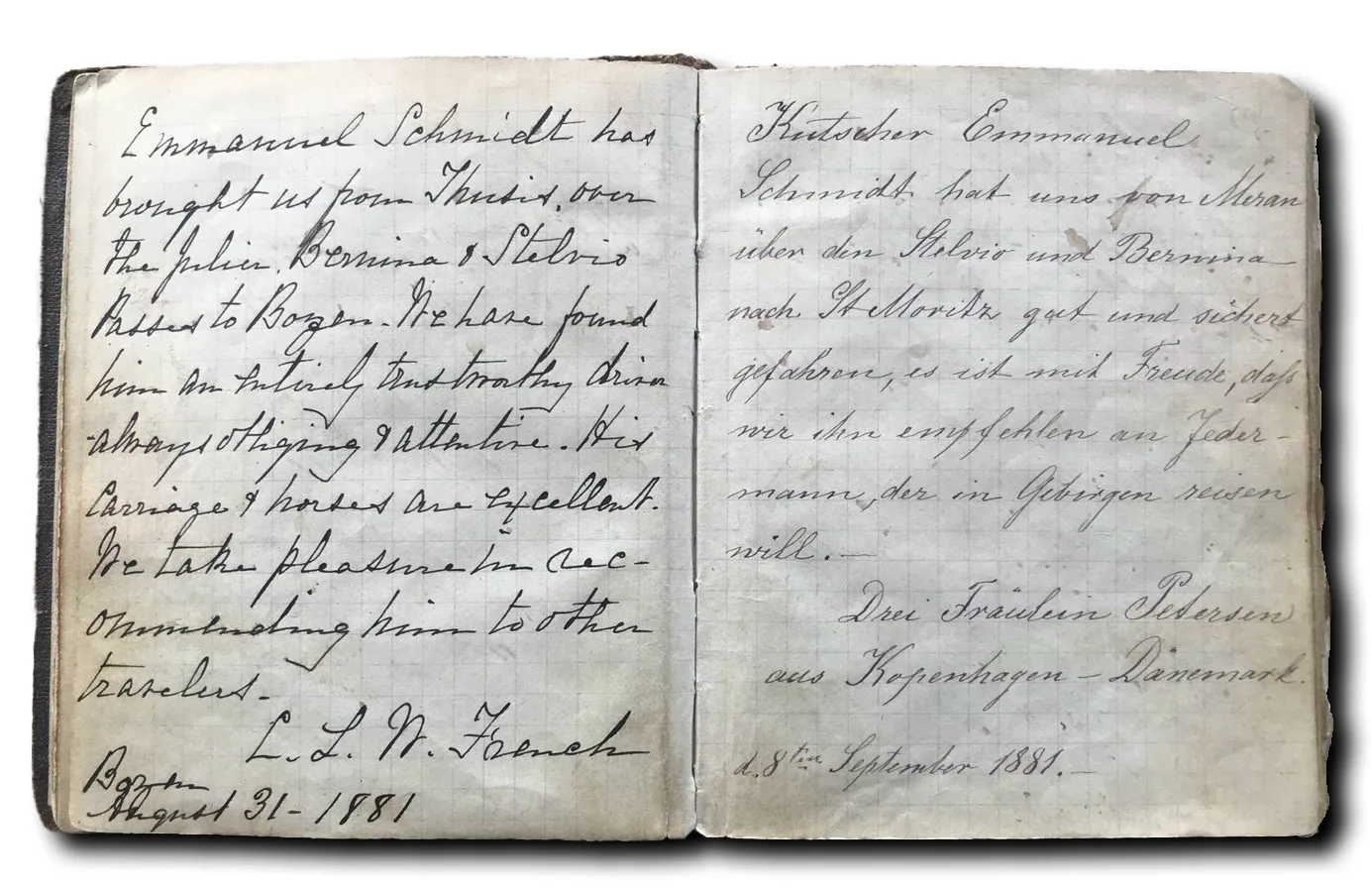

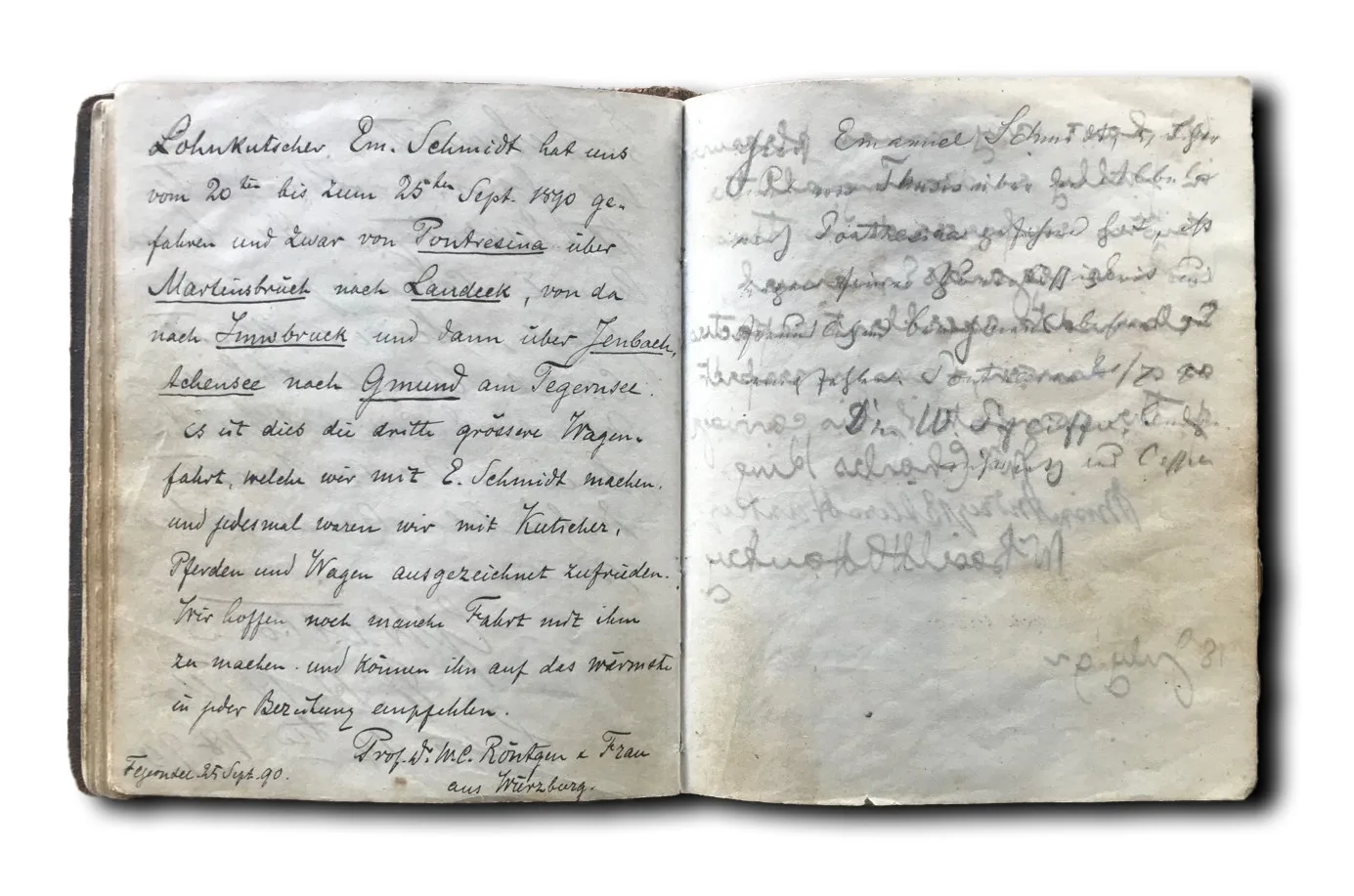

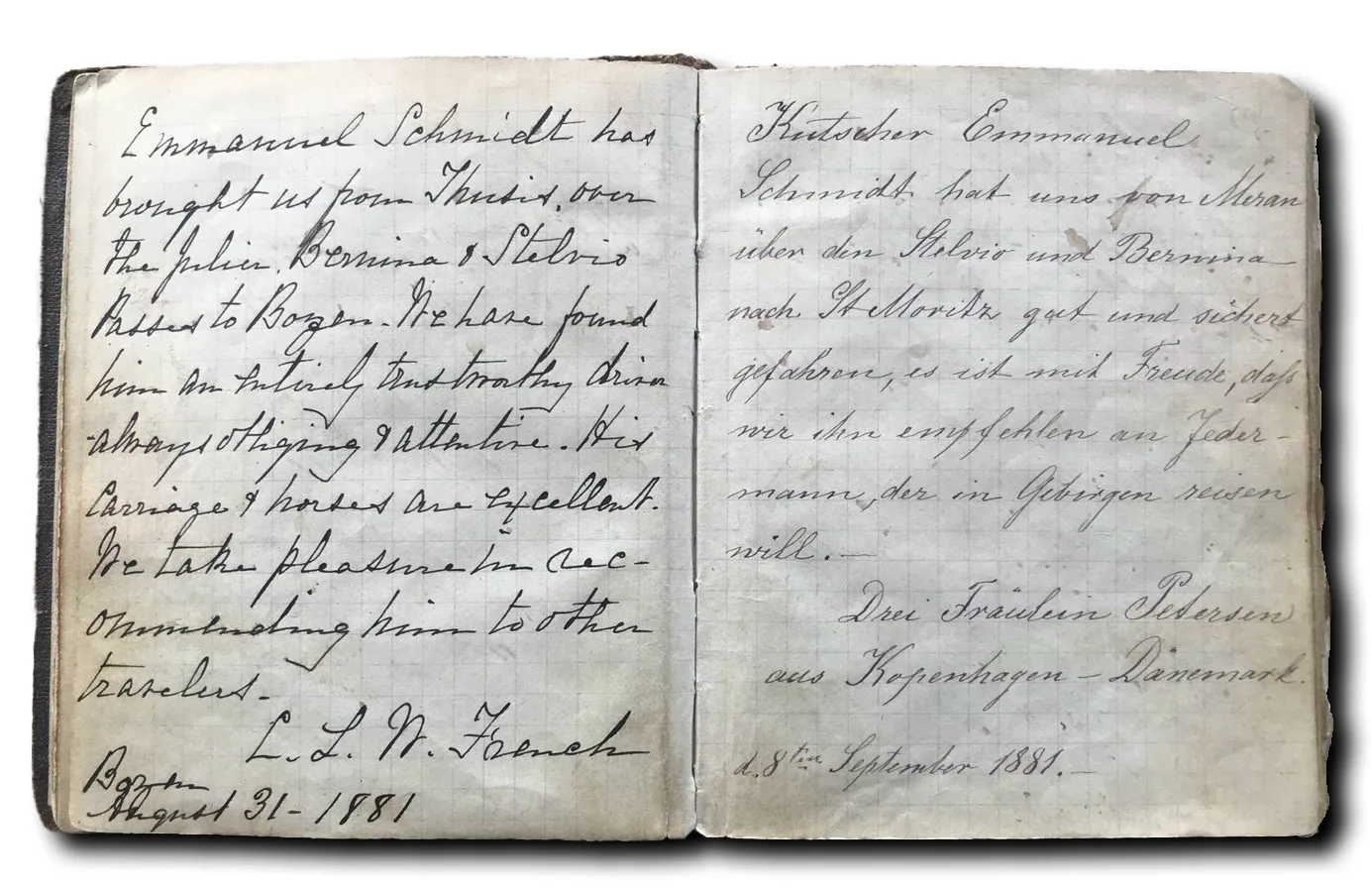

![Left-hand side: “Emanuel Schmid drove me and my family from Chur to Biasca, and I would like to express my complete satisfaction with the carriage and horses, Mr Schmid’s talent as a coachman, and his courteous and friendly manner. Biasca 31 Aug [18]82, Leopold Iklé from St. Gallen”.](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/ikle-lohnkutschrei-1882.webp)

Coachman Emmanuel Schmid from Graubünden regularly drove his famous passenger Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen around the Alps in the late 19th century.

![Left-hand side: “Emanuel Schmid drove me and my family from Chur to Biasca, and I would like to express my complete satisfaction with the carriage and horses, Mr Schmid’s talent as a coachman, and his courteous and friendly manner. Biasca 31 Aug [18]82, Leopold Iklé from St. Gallen”.](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/ikle-lohnkutschrei-1882.webp)