Illustration: Marco Heer

A nut of the world

Up to the early modern era, the coconut was considered an exotic rarity from the New World. It was believed not only to protect against poisoning, but also to show sophistication.

Nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cramps, colic and internal bleeding – these are symptoms of arsenic poisoning. Kidney failure and circulatory collapse eventually lead to death within a few hours or days. Because arsenic has no taste or odour and is easily dissolved in liquids, it’s an especially insidious toxin – and perfect for attempted assassination by poisoning. It is lethal even in small quantities.

So in the late Middle Ages, what could you do to protect yourself against arsenic poisoning? Use a coconut, of course! Up to the modern era, the coconut was claimed to have magical curative powers. It was thought to indicate the presence of pathogenic ingredients or poisons by frothing or changing colour. In a best-case scenario, it would even neutralise the poison. The owner of a coconut thus had on hand an ‘aid against unseen poisoners’.

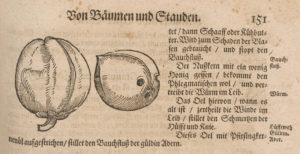

In Adam Lonitzer’s 1557 Kreuterbuch (Book of Herbs), the coconut is hailed as a remedy for bladder problems, hip and knee pain, worms and phlegm.

ETH Bibliothek, e-rara

EXOTIC RARITY

So anyone who could call a coconut their own counted themselves extremely lucky. With the discovery of new sea trade routes, the volume of imports of this exotic fruit into our part of the world increased. In addition to coconuts, other exotica brought to Europe during this period included coral branches, ostrich eggs, rhinoceros horns, turtle shells, elephant tusks, narwhal tusks (presented as the horn of the mythical unicorn), porcupine fish and buffalo horns, which were thought to be griffin claws. For the ‘civilised’ world, these exotic curiosities represented the spoils of colonialism.

In Europe these oddities were embellished with valuable precious metals, transforming them into unique handcrafted treasures. This created the perfect fusion of nature and art: naturalia, God’s creations, and artificialia, human creations, were combined in one object.

Many of these treasures found their way into the private ‘cabinets of curiosities’ of wealthy aristocrats and rulers. They were shown to visitors to impress them, and to convince them of the affluence, knowledge and sophistication of those who owned such riches. Such collections were supposed both to represent the world in miniature, and to reflect the place of humankind in the universe. With their accumulations of exotic objects, the assemblers of these cabinets of curiosities sought to gain the admiration and respect of their guests.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, elaborate coconut trophies were found in the cabinets of arts and curiosities kept by Europe’s wealthy elite.

Swiss National Museum

Thanks to new overseas trade routes, the prosperous middle classes could also afford exotica, and bought up precious, unusual and rare things, as attested by inventories of inheritances and bequests. When Elsbeth Burger married in 1546 her dowry included, along with 26 different cups, a ‘muscat nut’, as coconuts were called, fashioned as a drinking vessel. And on his death in 1572, the distinguished Zurich guild master Jakob Sprüngli left behind a trove of silver treasures that included a decorative coconut. One can only speculate as to its purpose. But it certainly served as an ornament and as a status symbol. Whether these coconuts ever actually saved an owner from an attempted poisoning has never been documented, unfortunately. But merely believing in the protective potential of the coconut probably made its owner feel better.