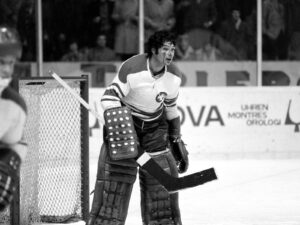

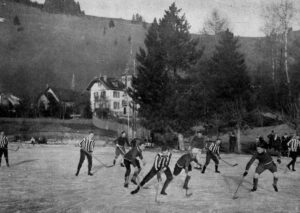

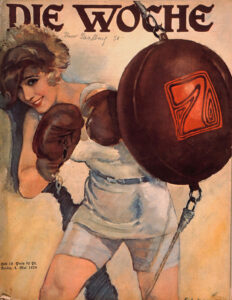

Ice hockey — a hard man’s sport?

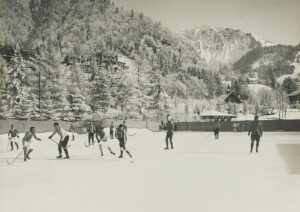

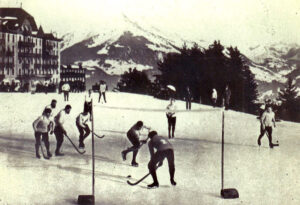

Sport always reflects gender roles and images. Ice hockey being a rather extreme example. This is largely due to the way in which the sport has evolved.

Programme on women in ice hockey from 3 December 2000. RTS

Swiss Sports History

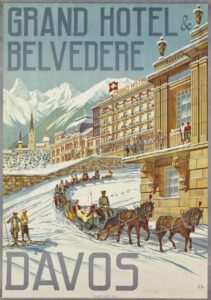

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch