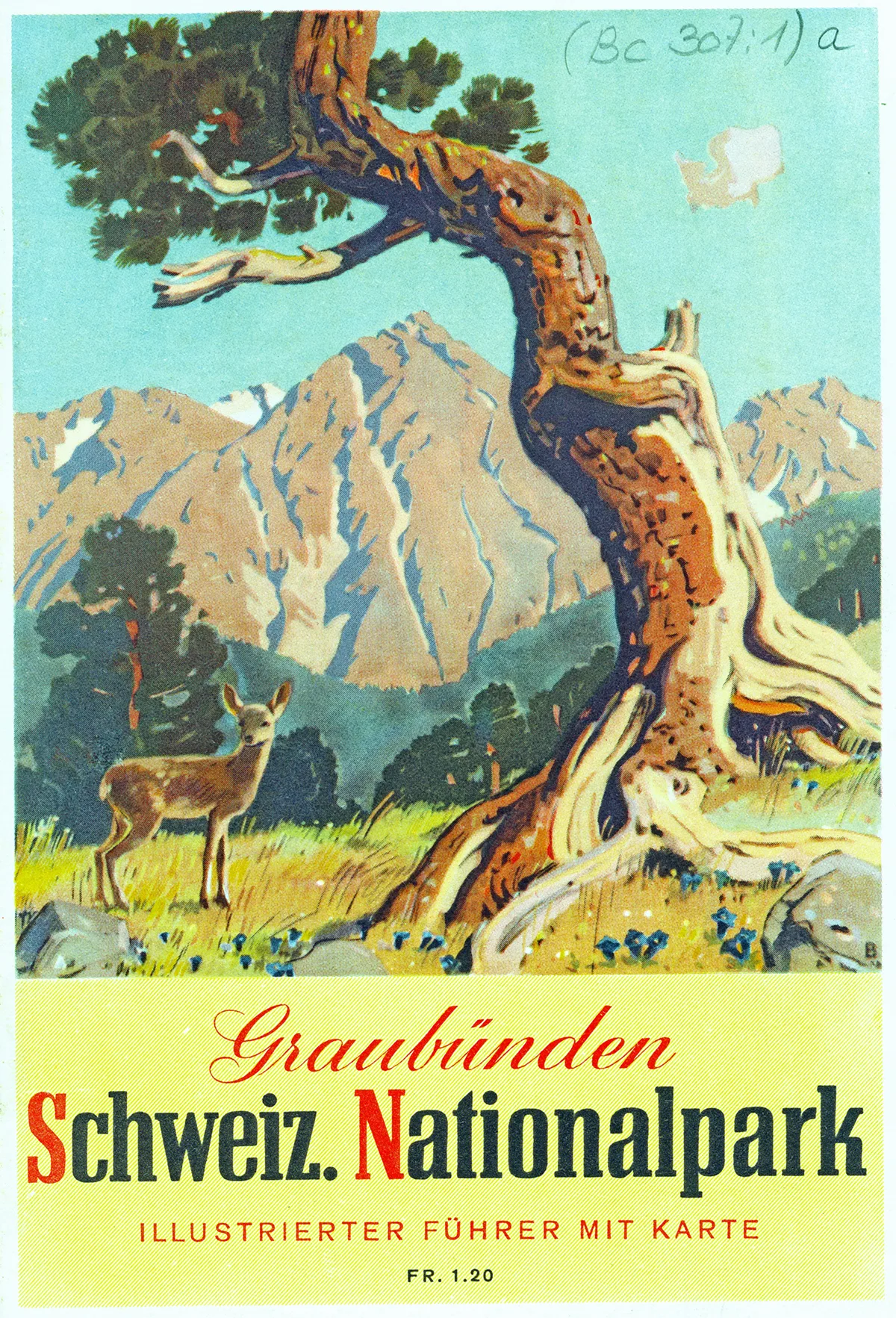

The birth of the Swiss National Park

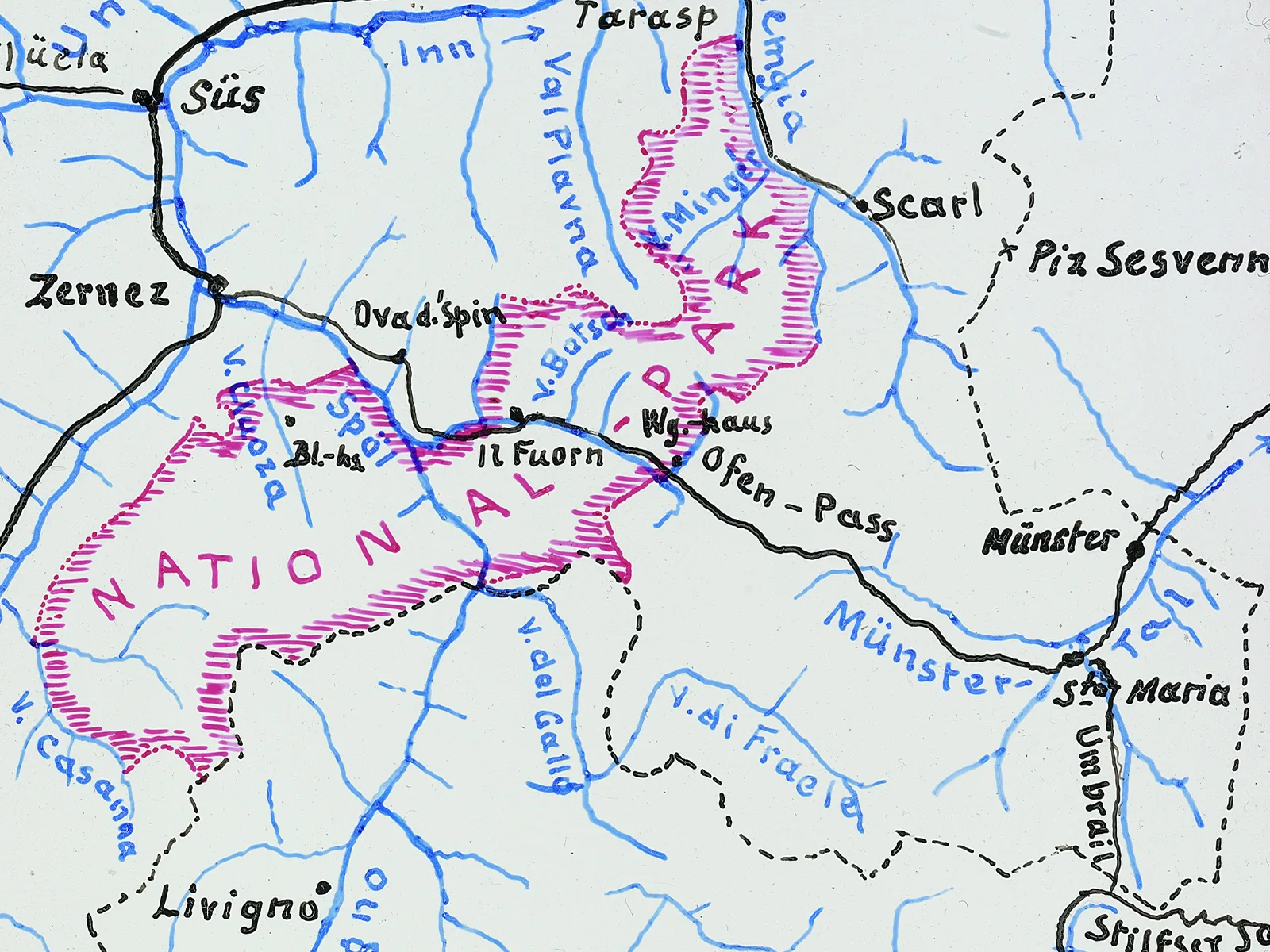

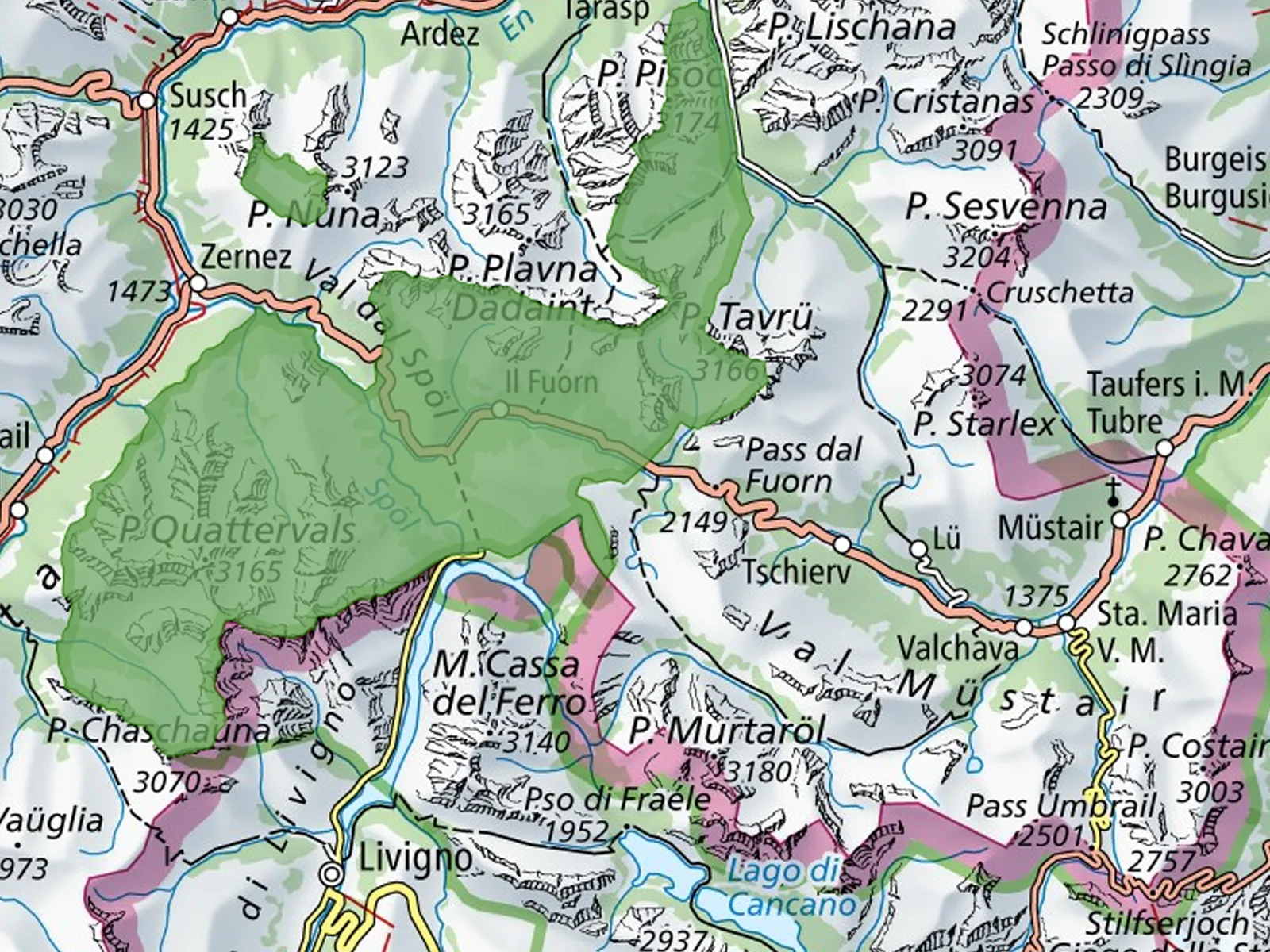

Around 150 years ago, things were looking grim for Switzerland’s flora and fauna. Then two Basel academics seized the initiative, and set about bringing to life their vision of an unspoiled, primordial landscape in the Engadin. In 1914, the first national park in Central Europe was opened in the Val Cluozza.