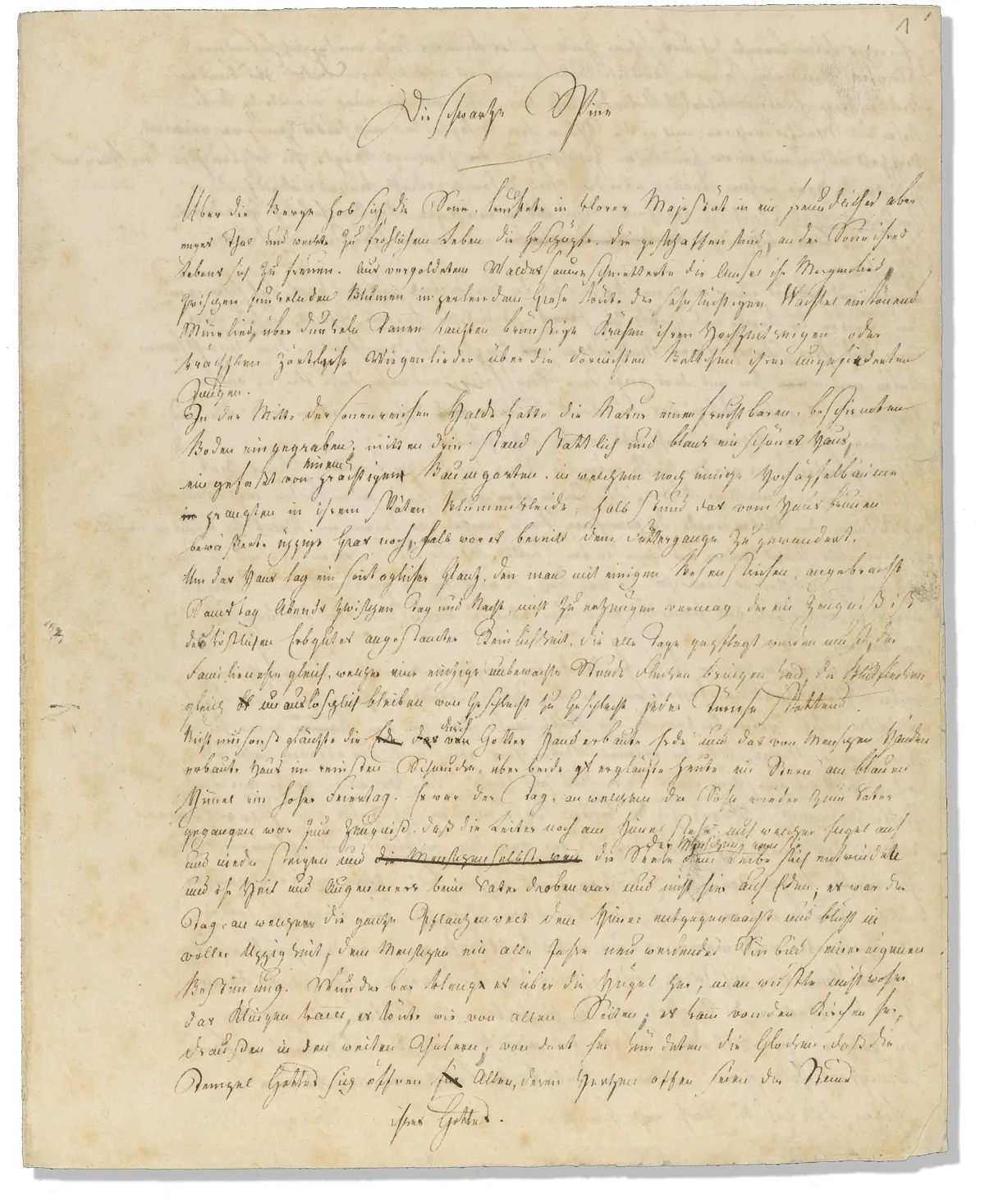

The forest of the Black Spider

Gotthelf’s novel “The Black Spider” explores themes of greed, conflict and the power of the plague. But the author also voices his frustration over unchecked forest clearance in his home canton of Bern.

My castle is ready, but one thing is still missing: summer is coming and there is no shady path out there. In one month you are to plant me an avenue of trees; you are to take a hundred full-grown beeches from the Münneberg, with branches and roots, and you are to plant them for me on Bärhegen, and if a single beech is missing, you shall pay for it with your property and your blood.

Trailer for the Swiss feature film "Die Schwarze Spinne", 2022. AscotElite / YouTube