The changing face of football fandom

What a party! Chanting fans, fireworks, cheering and applause coalesce in a sea of flags – for many people, these scenes are rowdy, intimidating, uncivilised and uncouth. For others this is the highest of highs, an eruption of fan euphoria representing a cultural phenomenon that is now widespread, but about which very little is known.

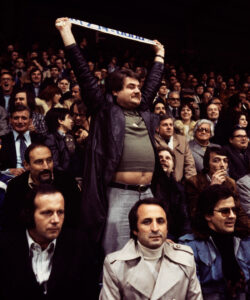

From Sunday best to denim vest

The ultras come, bringing culture

A study by the University of Neuchâtel shows that militant football fans are not out for violence; they’re there for the emotions. SRF Tagesschau piece on the subject of “Ultras”, 6 May 2008 (in German). SRF

Choreography of FC St Gallen fans in a game against BSC Young Boys. YouTube / Michael Weigl

Outside the stadiums

“Kämpfe bis zum Schluss” (Fight to the finish) by Basel rapper TripleNine, 2013. YouTube / FetchOnFire Bonvinvant

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch