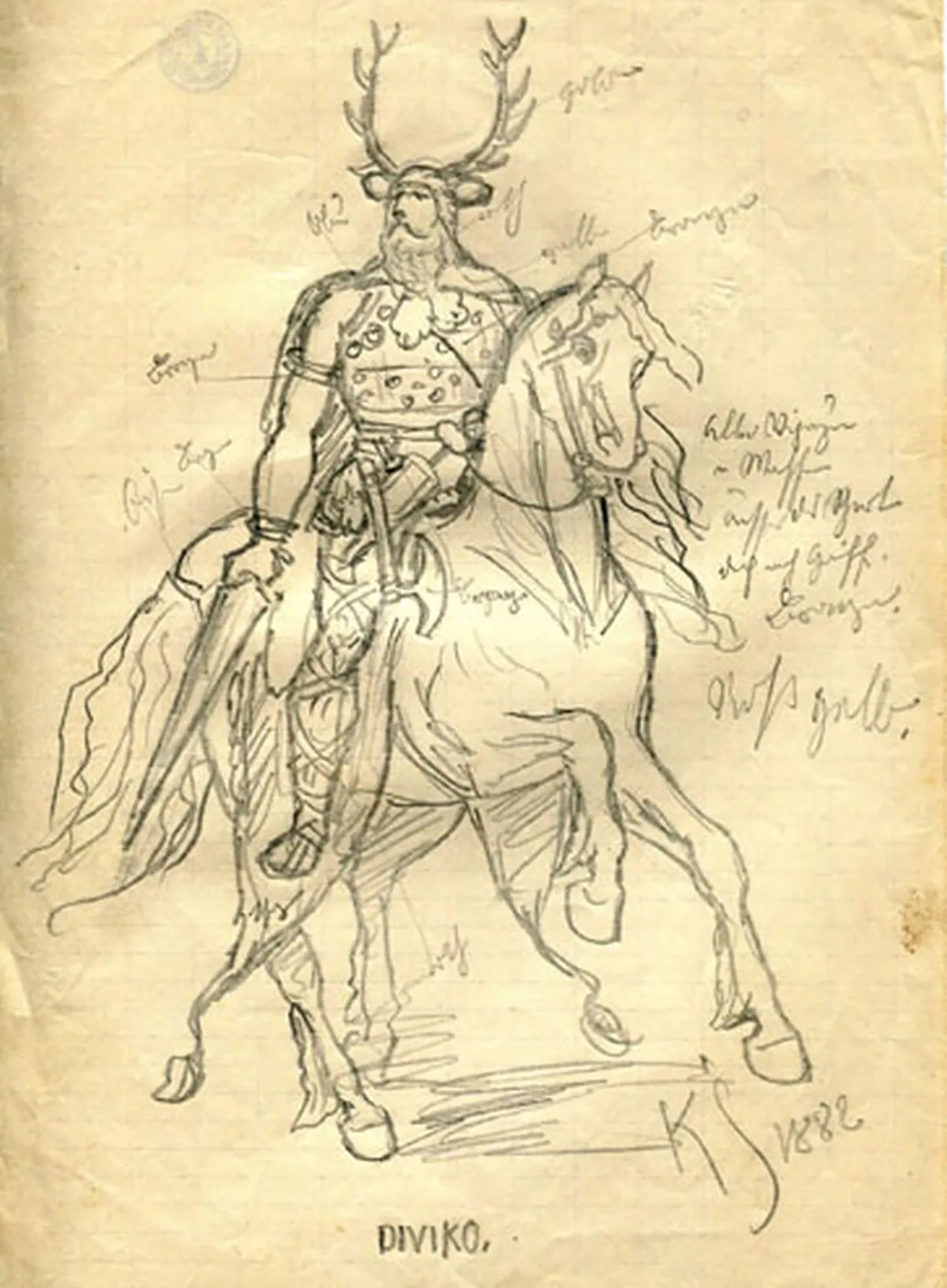

Divico – a forgotten national hero

Around 200 years ago, just when there was a shortage of heroes, the myth of Divico was born. As the chief of the Tigurini people of Helvetia, he made history on account of his brave deeds and the often disrespectful way he talked to Julius Caesar.