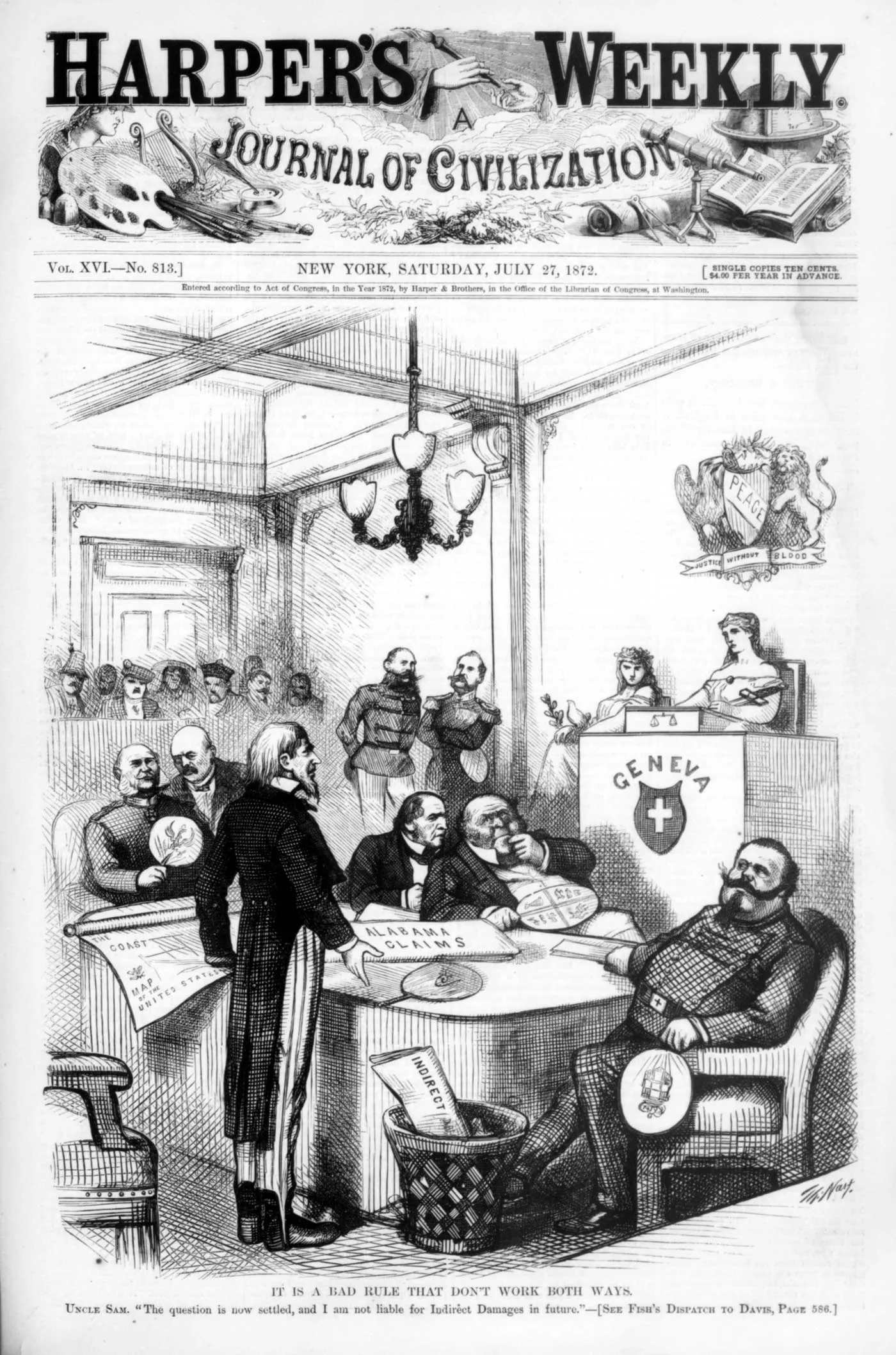

Impartial? Refereeing through the ages

Referees are ostensibly portrayed as impartial. At the same time they attract controversy. It’s time for a look back at how the idea of arbiters applying the letter of the law, whether in the courtroom or on the sports ground, all began.

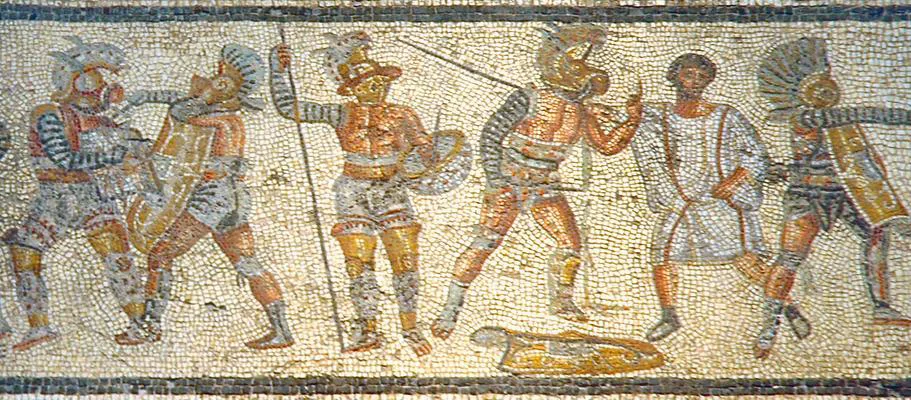

From gladiatorial contests to ensuring fair play

From captain to referee: the evolution of officiating in football

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch