King, servant, coral diver

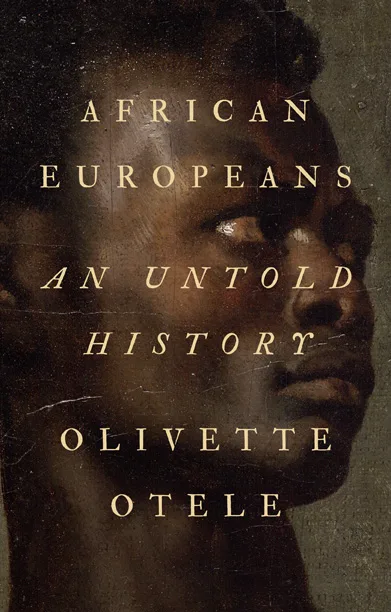

Africans have been present in Europe for centuries. If you keep your eyes peeled as you stroll around the art museums of Europe, you’ll encounter them depicted in a wide variety of roles.

People of colour in European art collections

Black gondolieri

Colonial history(ies) in oil