Minor language, monumental work

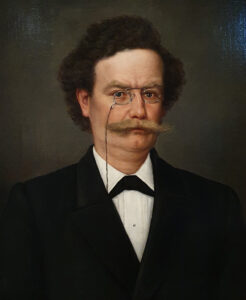

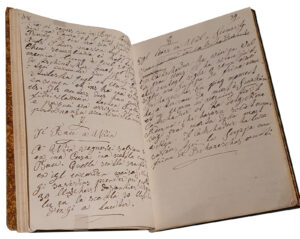

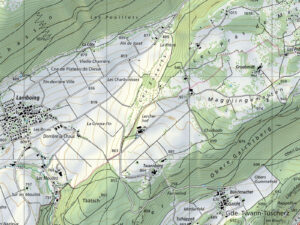

In his ‘Rätoromanische Chrestomathie’, unconventional Graubünden politician and cultural scholar Caspar Decurtins (1855-1916) created the most important older source text on the Romansh culture of his home canton. And did so while accomplishing a great deal more.