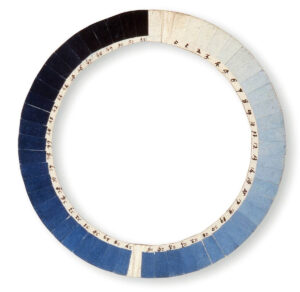

The blue of the sky…

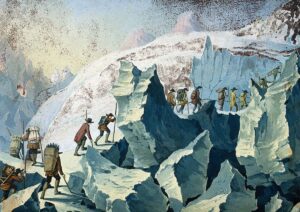

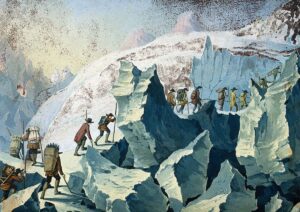

In August 1787, Genevan naturalist Horace Bénédict de Saussure climbed Mont Blanc with the aim of answering a seemingly childish question: why is the sky blue?

In August 1787, Genevan naturalist Horace Bénédict de Saussure climbed Mont Blanc with the aim of answering a seemingly childish question: why is the sky blue?