Swiss National Museum

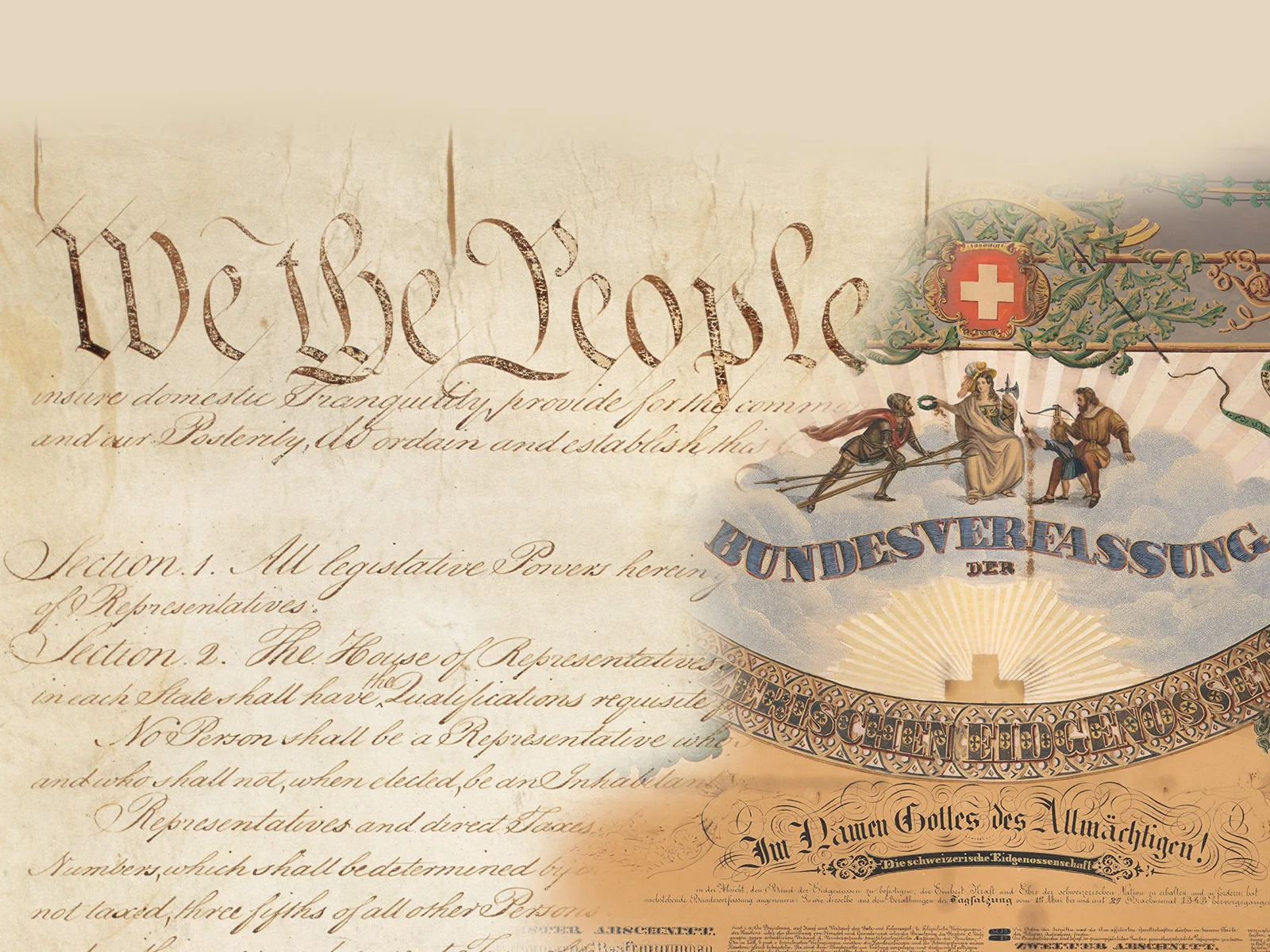

Agricultural revolutions in Switzerland

The modernisation of agriculture in Switzerland stretched over two centuries, from the systematic use of farmyard manure to harnessing working animals and the motorisation of many work processes.

The modernisation of agriculture is more akin to a process than an event, since the farming population has always sought to improve the soil-based exploitation of plants and animals. But the extent to which this was achieved depended on the constantly changing climatic, technical and institutional conditions in which all agricultural production is embedded.

Vital but, generally speaking, hardly revolutionary changes in food production occurred during the period which has long been referred to in the literature as the ‘agricultural revolution’, from around 1700 to 1850. This is related to the fact that in the era of the economic enlightenment sections of the elite began to take an interest in agricultural issues. Often building on practices in use by peasants like Jakob Gujer for a long time, economic patriots like Johann Rudolf Tschiffeli in Bern campaigned throughout Europe for the privatisation of the common lands hitherto used collectively by villagers, for keeping the animals in stables all year round, and for the cultivation of ‘new’ plants such as potatoes and clover which, as it grows, can bind nitrogen from the air and fix it in the soil.

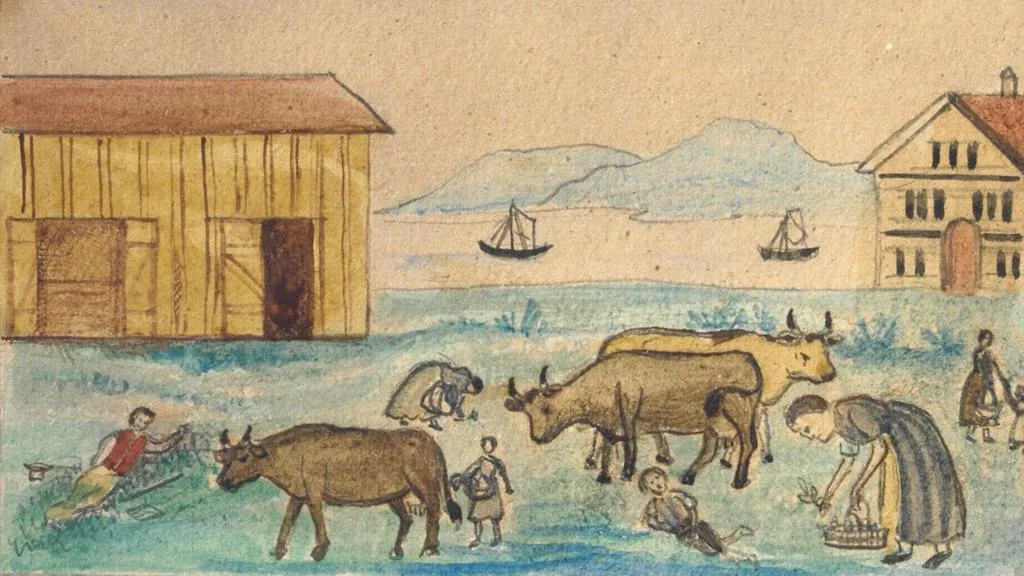

Women planting out potatoes. The picture was taken in the late 19th century.

Swiss National Museum

With livestock being kept indoors also in summer, the organic manure could be collected and more systematically applied to the areas of land used for crop cultivation. As a result, grain yields increased, meaning larger areas were now available for producing fodder for more animals. The growing livestock population, in turn, provided not only more milk and meat, but also more manure and slurry. For the first time in history, the nutrients taken out of the soil in the process of plant-growing could systematically be returned back to it. Fallow, therefore, in many places became obsolete.

Characteristic for the expansion of agricultural production during the first agricultural revolution is, that it took place without having access to the resources inside the Earth (the lithosphere). Expansion therefore remained limited, within the constraints that distinguishes the use of living resources from the consumption of fossil provisions. Extraordinary weather- and climate-related setbacks, therefore, still resulted in contraction processes so that even in Western Europe scarcity and hunger persisted into the mid-19th century.

Although production was expanding in the 18th century already, hunger crises persisted up to the middle of the 19th century. Painting of the famine of 1817, the ‘year without a summer’. People in Toggenburg eating grass in the fields.

Toggenburger Museum Lichtensteig

Big changes in agriculture

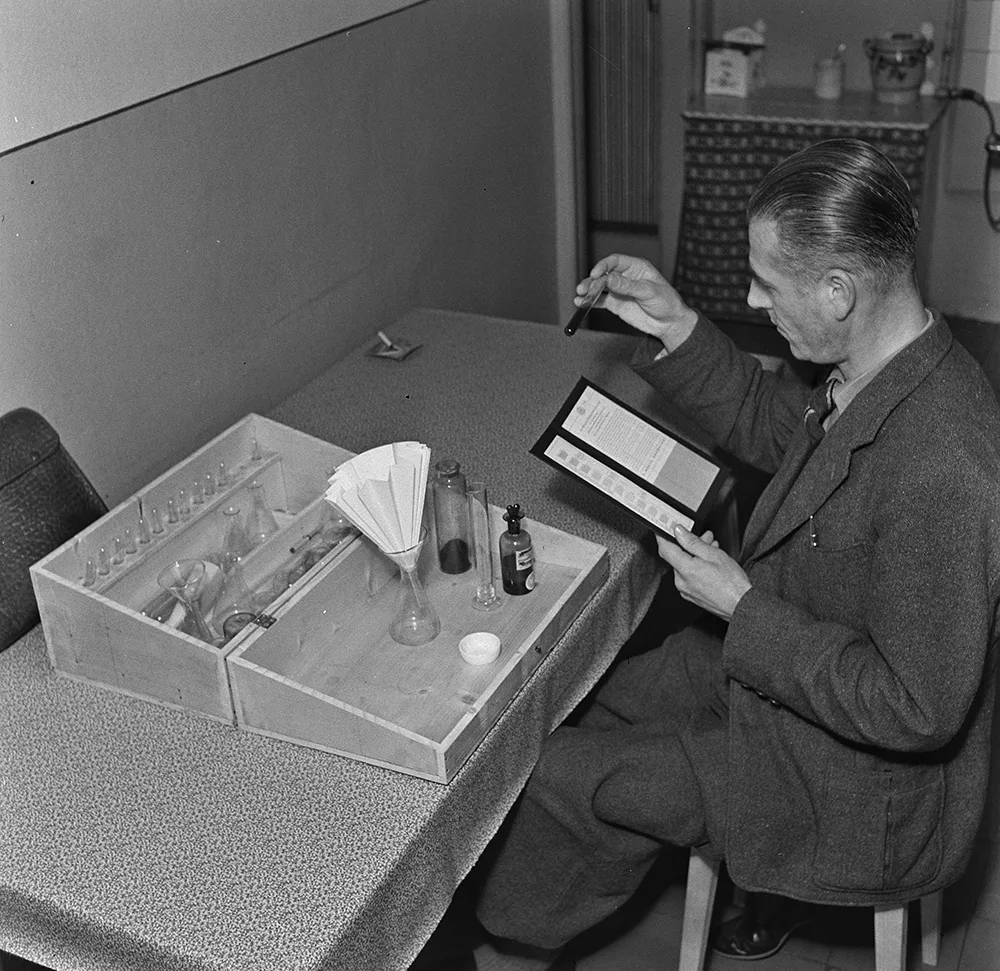

That didn’t change until the second agricultural revolution, which lasted roughly from 1850 to 1950. While the limited agricultural growth during the first agricultural revolution had contributed a great deal to the industrial revolution and the increase in population, key achievements of the industrialised societies such as chemical fertilisers and reaping machines now made an impact on agricultural production. Reciprocally agricultural commodities such as milk, meat and leather became important staples for the food and clothing industries. From the 1880s onwards, this mutual exchange of goods at national and transnational levels was primarily organised by cooperatives. The main producers cooperative was the Verband Ostschweizerischer Landwirtschaftlicher Genossenschaften (association of agricultural cooperatives), or VOLG, for the consumers it was the Verband Schweizerischer Konsumvereine (association of Swiss consumer societies) or VSK, now known as Coop. In 1898, the VSK and the VOLG affiliated to form the Schweizerische Genossenschaftsbund (Swiss cooperative alliance). The systematisation and ‘scientification’ of animal and plant breeding also contributed towards a significant growth in agricultural production which in the period of the second agricultural revolution merely lagged slightly behind that of industry.

Fertiliser dosing test, 1941.

Swiss National Museum/ASL

It was only during the third agricultural revolution, in the latter half of the 20th century, that growth in agricultural production matched that of the production of goods in industry. The motorisation and chemicalisation of agricultural production now made this extraordinary development possible. It was based on the consumption of resources from the lithosphere, the basis of industrial production since the early 19th century. The fact that between 1950 and 1985 alone agricultural production increased more than in the preceding 150 years, is also linked to the availability of pesticides such as those produced by the firm Dr. Rudolf Maag AG. In addition, those areas of land which had hitherto been needed for the production of fodder for the countless working animals now contributed substantially to the hitherto undreamt-of expansion of food production. The mechanisation of agricultural production which took place during the second agricultural revolution had still been based to a large extent on the use of working animals (horses, donkeys, cows, oxen, bulls, dogs), whose food, like that of humans, had to be produced on soil in the biosphere.