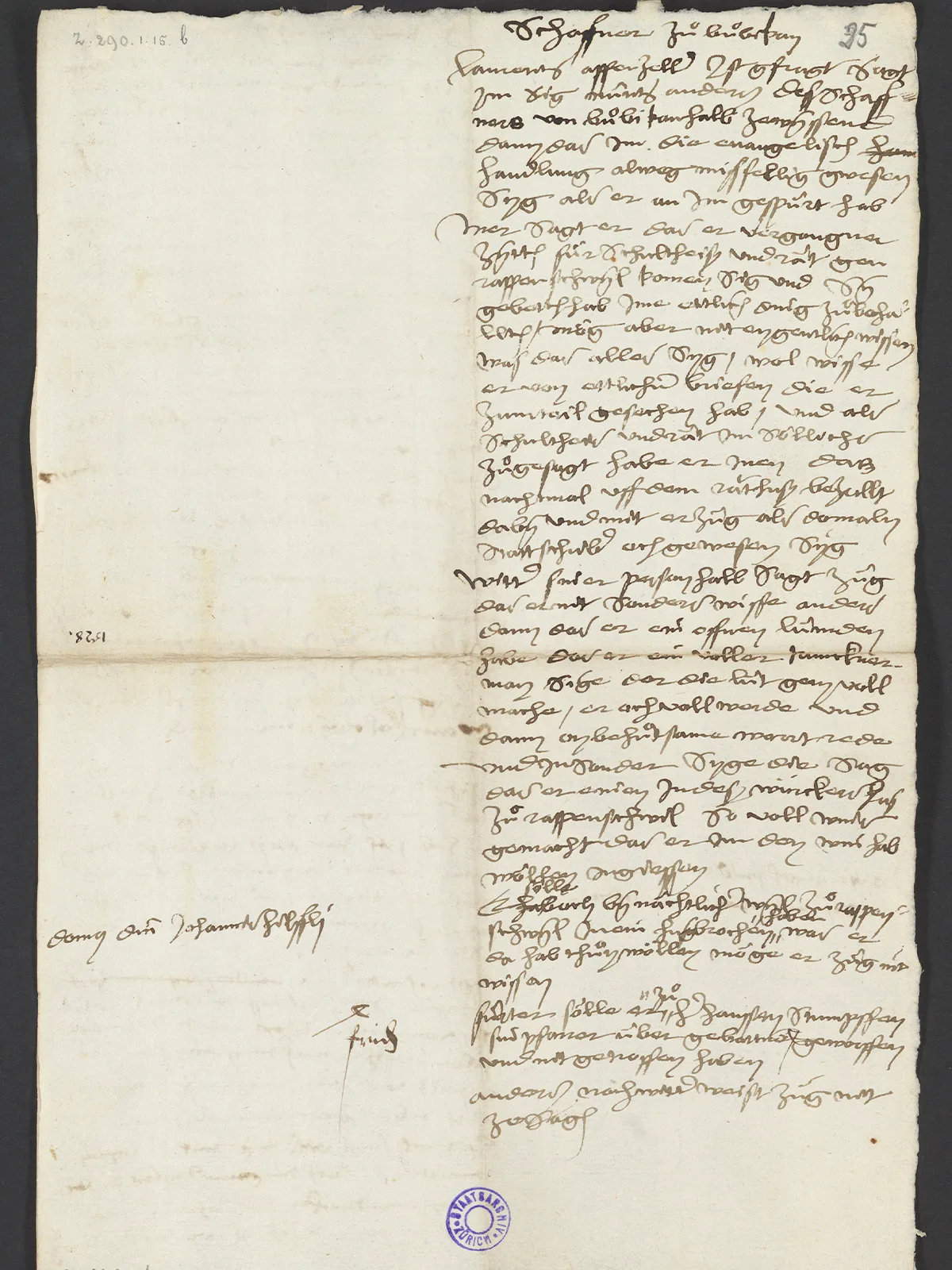

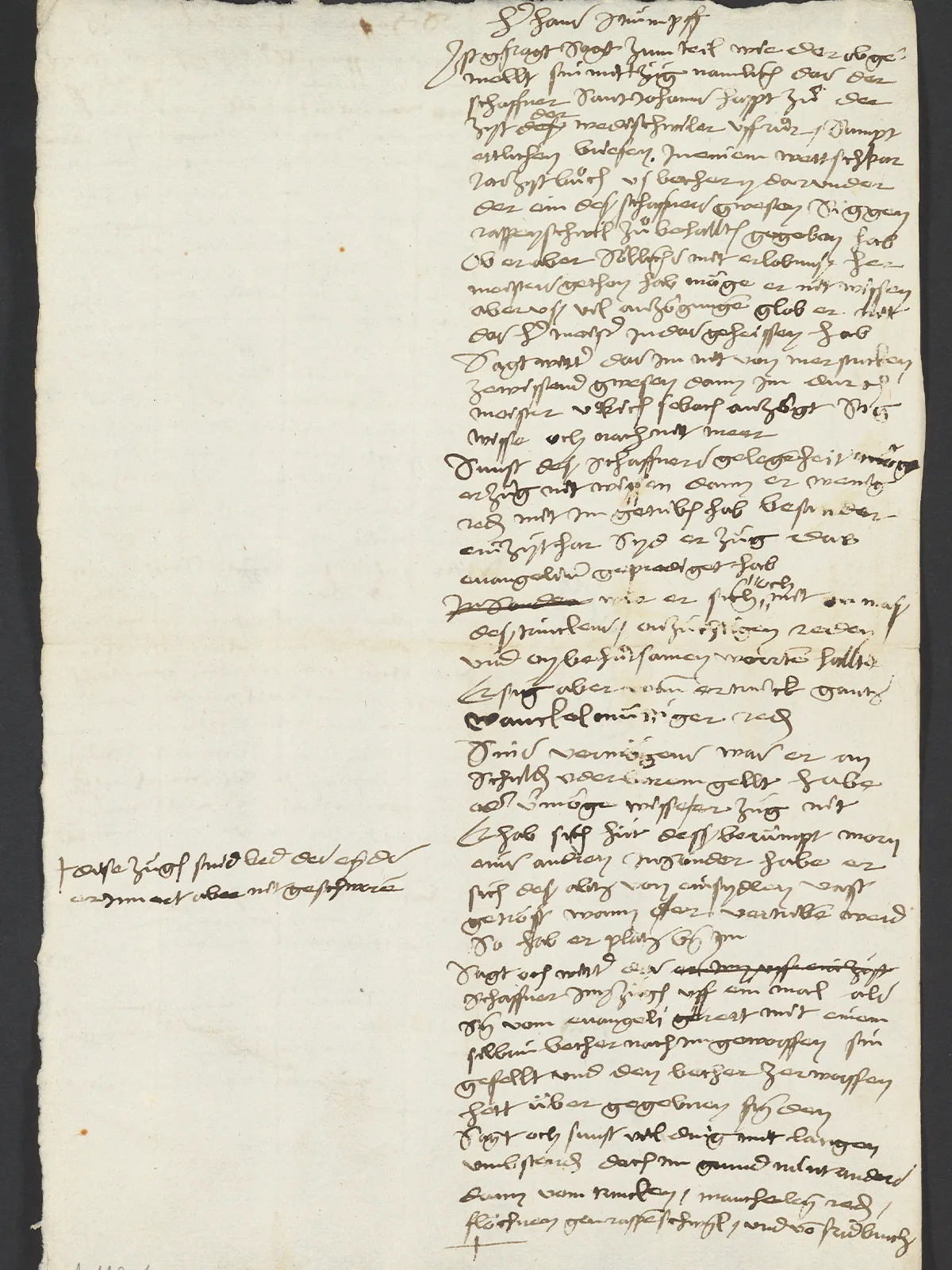

Bringing in the new faith by subterfuge

Not even the Order of Saint John was immune to quarrelling and intrigues. In 1528, the Zurich authorities succeeded in imposing the new Protestant faith through an intentionally wrongful arrest at the Bubikon Commandery.