Baroque: love it or hate it?

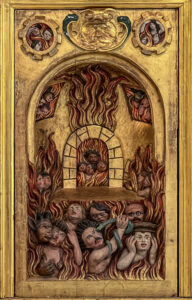

Here is a simple test. The pilgrimage church of Hergiswald at the foot of Mount Pilatus contains a visually stunning depiction of biblical scenes from the baroque period, circa 1650. What response does this cultural-historical cosmos elicit from you?

Dramatic impact

Stepping into a completely different world

Taken to the limits

Pointing the finger

A glimpse of life four centuries ago

Illusions

The ultimate in dramatic art

Baroque: love it or hate it?

All the photos in this blog were taken by Hermann Lichtsteiner, Lucerne: helifo.ch