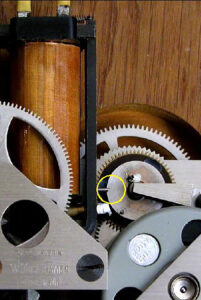

The iconic Swiss station clock

The Bundeshaus in Bern, Lucerne’s Kapellbrücke bridge, Geneva’s Jet d’eau: Switzerland has a whole host of landmarks. And yet there’s one of them to which we never give a second thought, even though we see it every day: the Swiss railway station clock.

At the full minute, the sweep hand on the SBB clock takes a short break. Swiss National Museum