Safien Valley’s roads: built by Polish soldiers

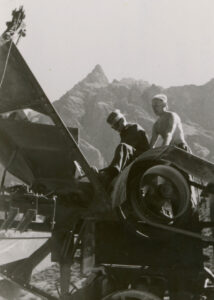

Polish and French internees built pathways and roads in many parts of Switzerland during the Second World War. They were especially busy in the Safien Valley – living under the most basic conditions.

French and Polish troops crossing the border. From the army film archives, June 1940. YouTube / Swiss Federal Archives

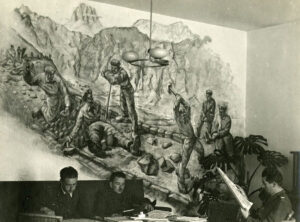

Working in the mountains was hard and required discipline. The Polish Museum, Rapperswil

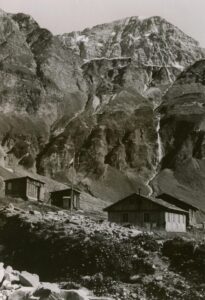

Lodging in a barn