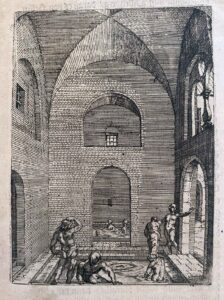

The “Kesselbad” and “Hell”…

In the Middle Ages and the early modern period, the thermal baths at Baden im Aargau played host to scores of distinguished visitors. These esteemed guests had access to exclusive baths and bathing areas with special amenities, and some of these areas are still preserved today.