The healing waters business

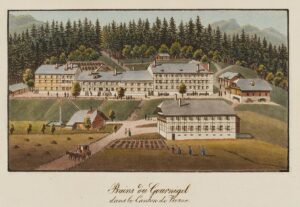

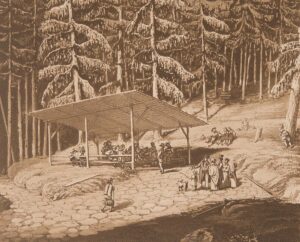

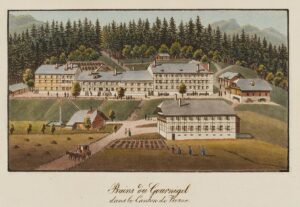

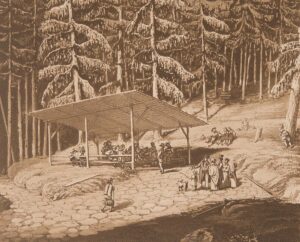

Water cures, a programme of activities and amusements, meeting place of the wealthy and the beautiful... In the 19th century, Gurnigelbad in the canton of Bern was a chic spa resort in the centre of the province...

Water cures, a programme of activities and amusements, meeting place of the wealthy and the beautiful... In the 19th century, Gurnigelbad in the canton of Bern was a chic spa resort in the centre of the province...