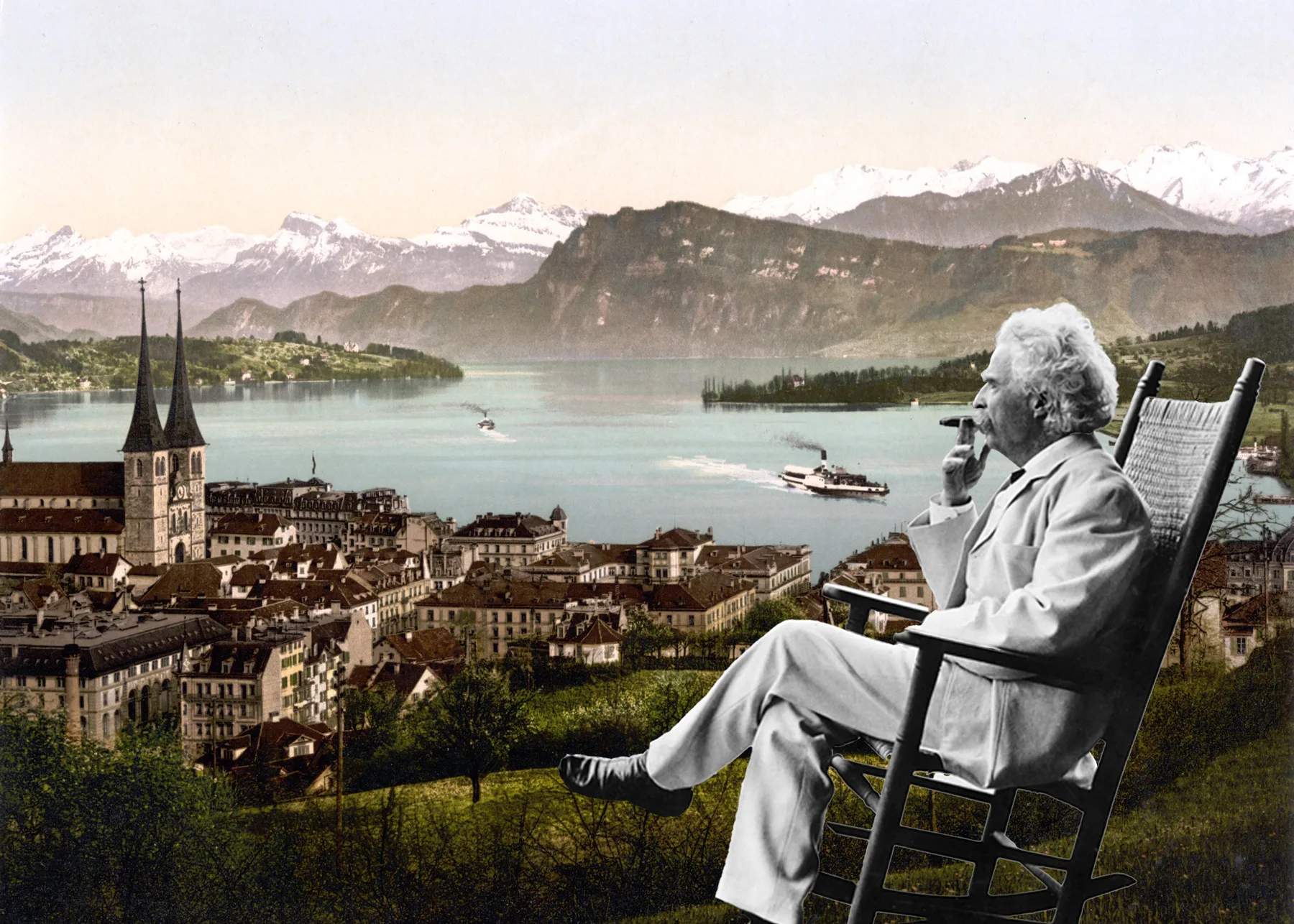

Amusing travel journal reveals Switzerland of 1837

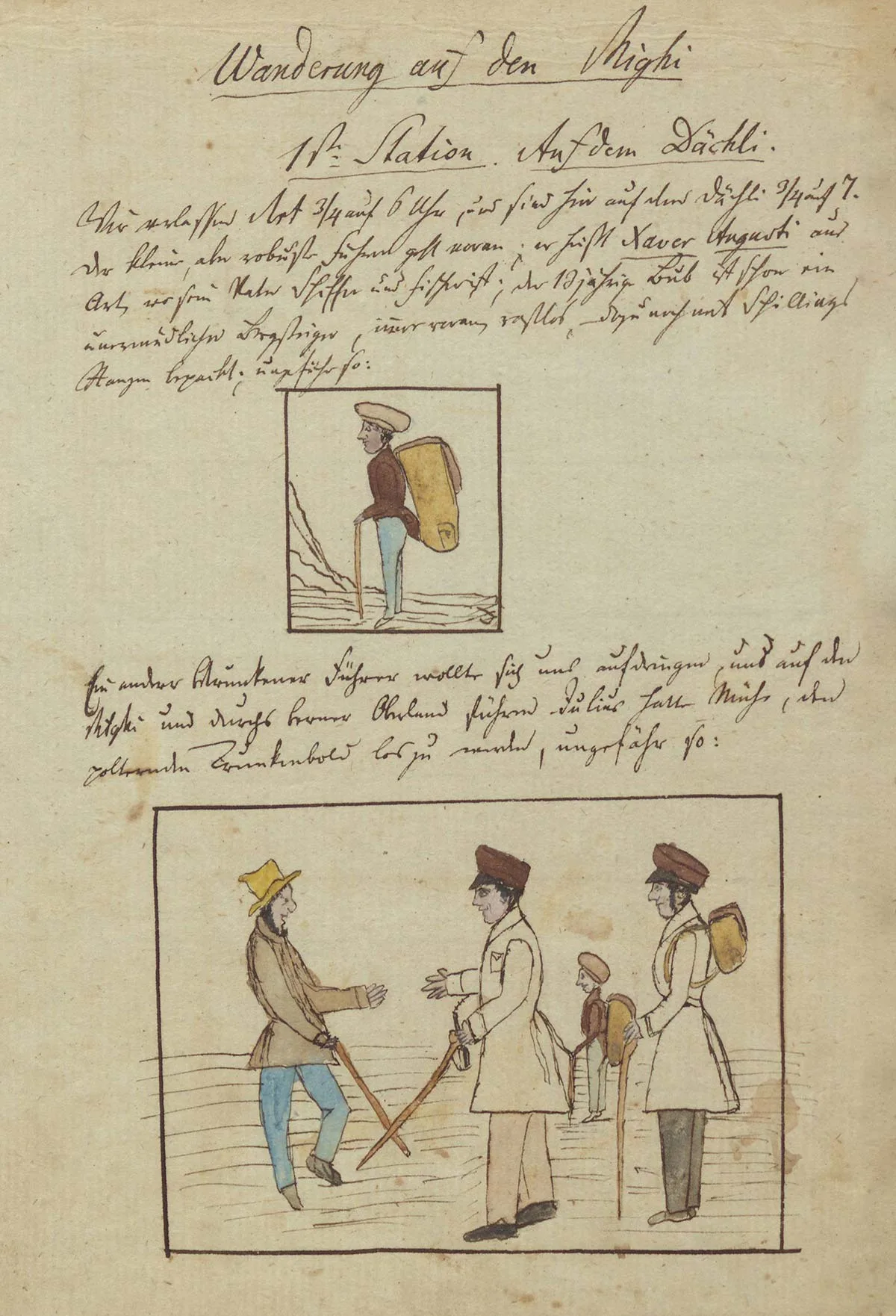

German theologian Carl August Wildenhahn documented his journey through 19th century Switzerland with humorous observations and comic strip-style pictures.

We were re-energised and within half an hour reached the summit (Rigi Kulm), where we got a friendly reception at the neat little inn. But there was little talk of the view – everyone was more interested in what was going on inside.”

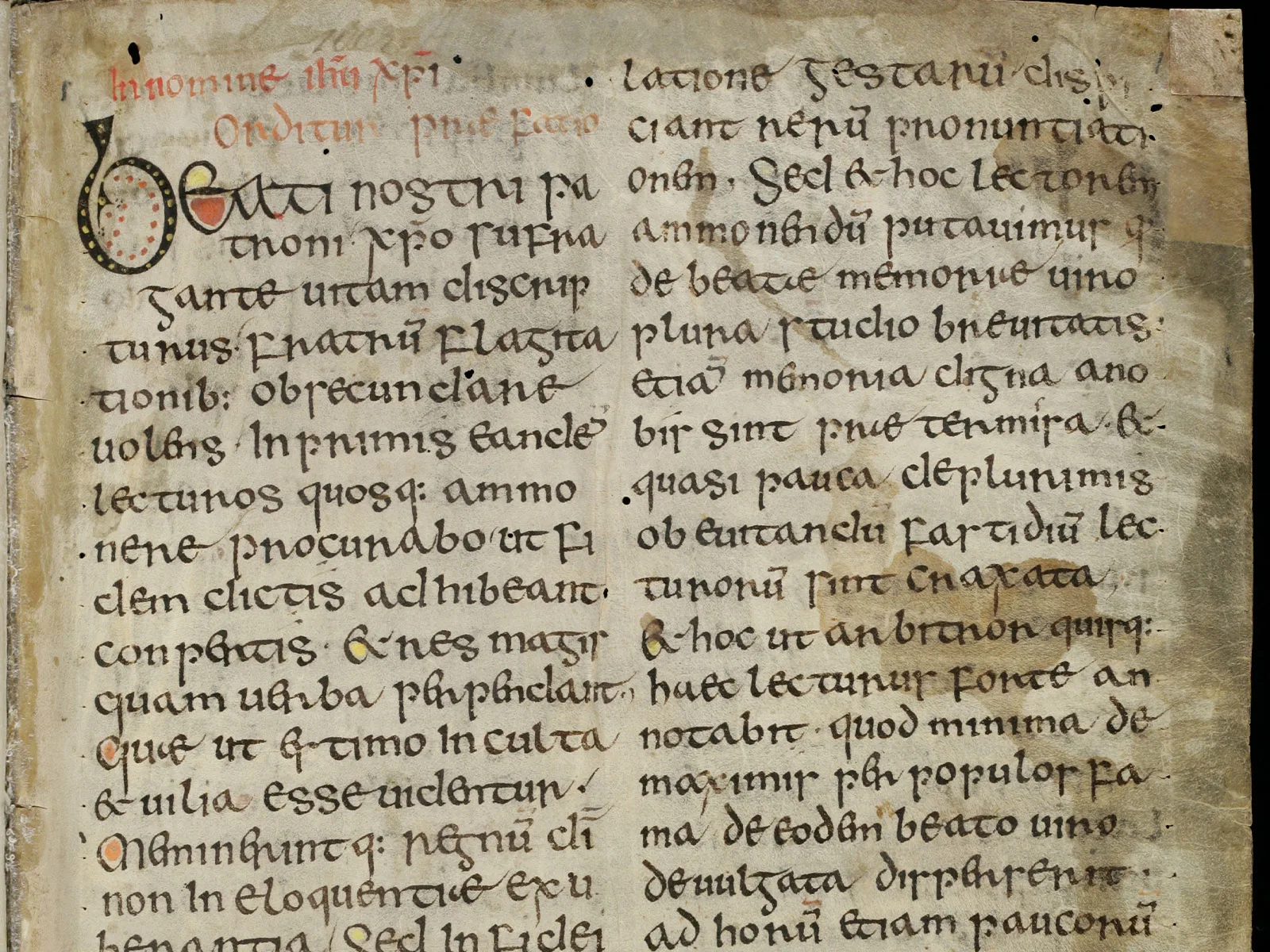

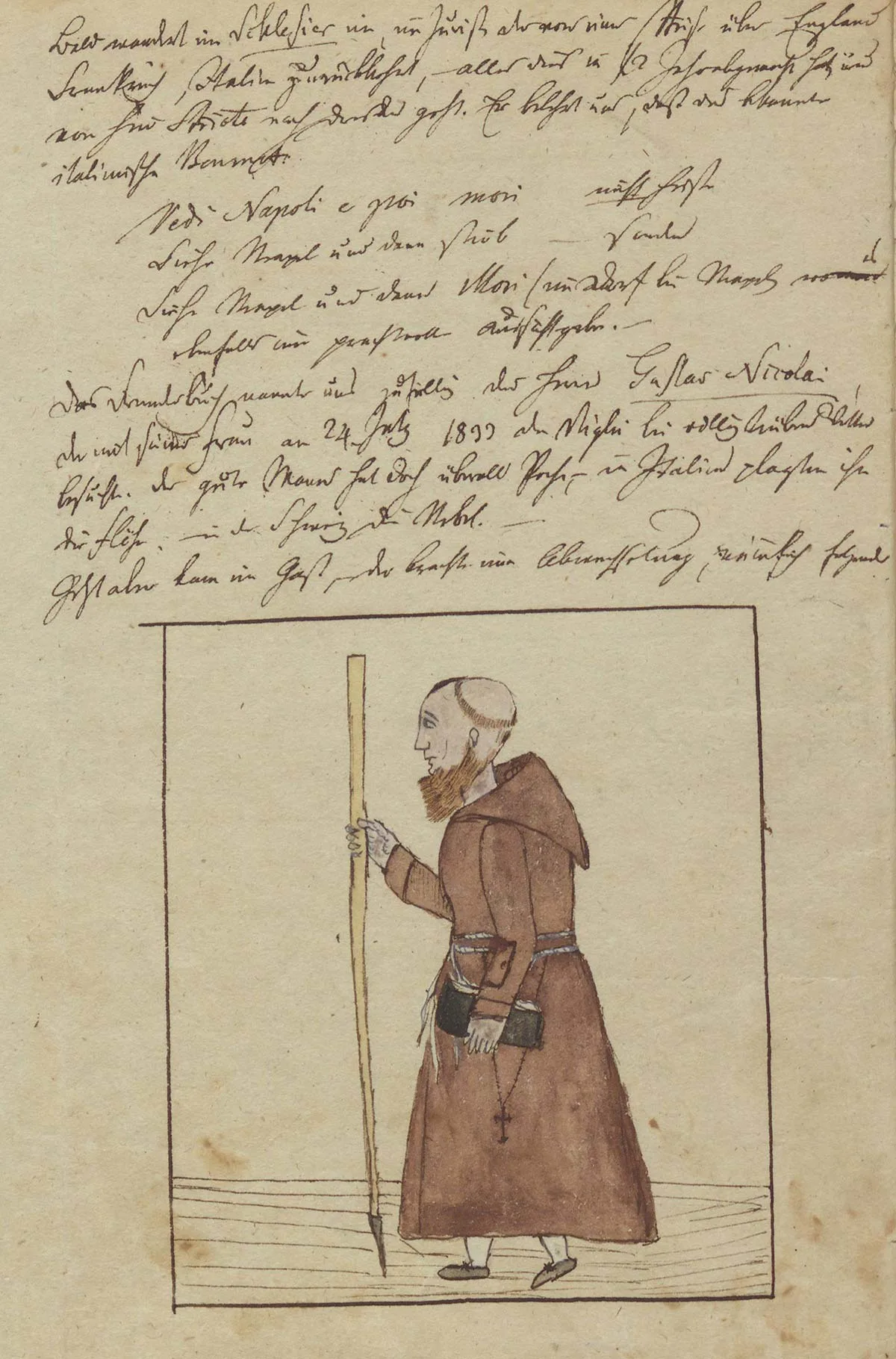

A Capuchin monk – a tall, thickset man wearing a brown robe, a white cord at his waist, a blue snuff handkerchief in his cowl, and in his sleeve pocket a tin of snuff which he busily inhaled without offering any around. He is the Father Superior at the monastery – he carries his Breviary around with him and enjoys the worldly pleasures of coffee, wine, bread and cheese that the Lord has bestowed upon him. I conversed with him in Latin, which he seemed to struggle with, but we managed. I offered him a cigar – which he refused. He told me nobody else in the monastery smokes either, although it’s not forbidden.

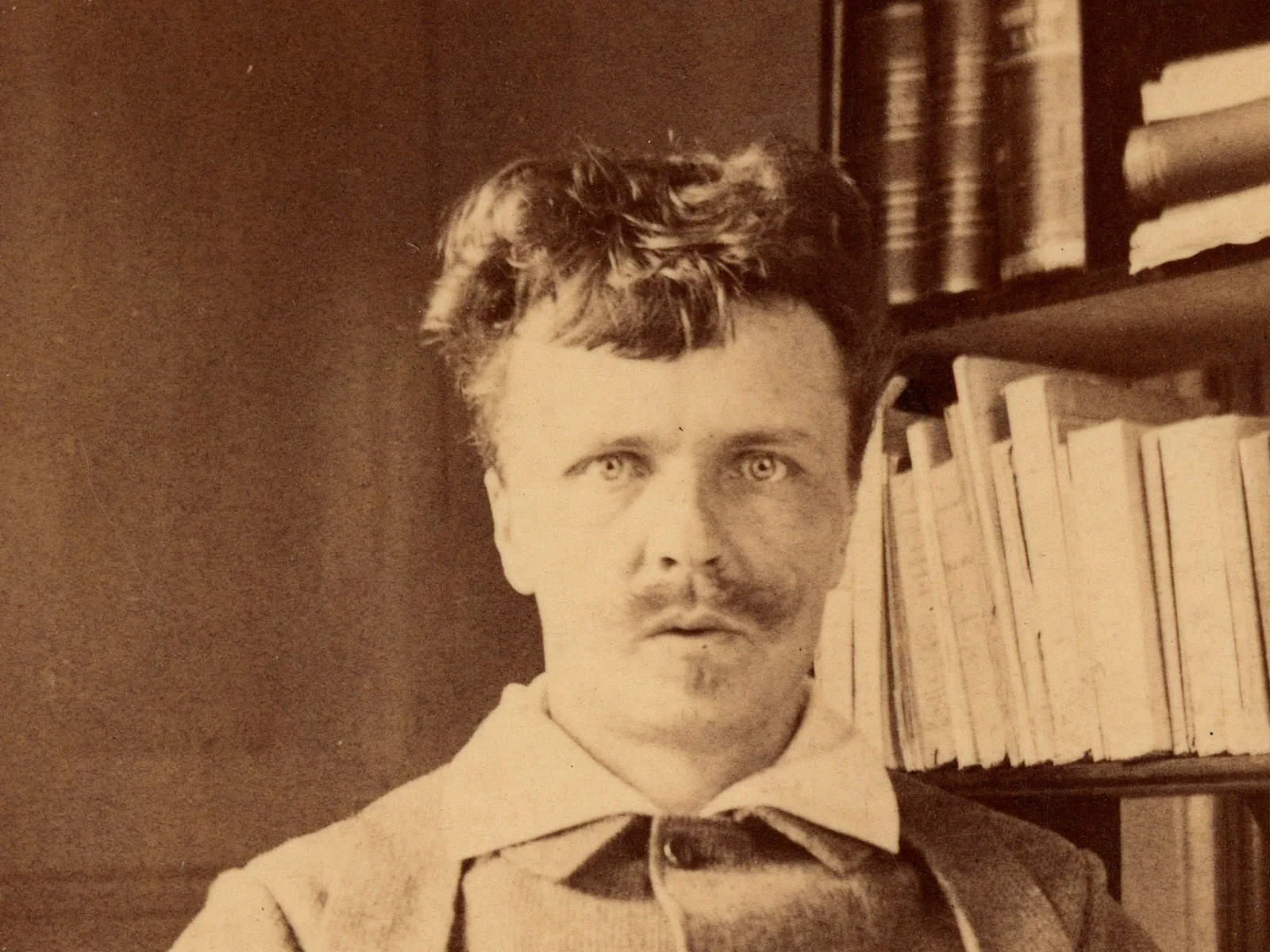

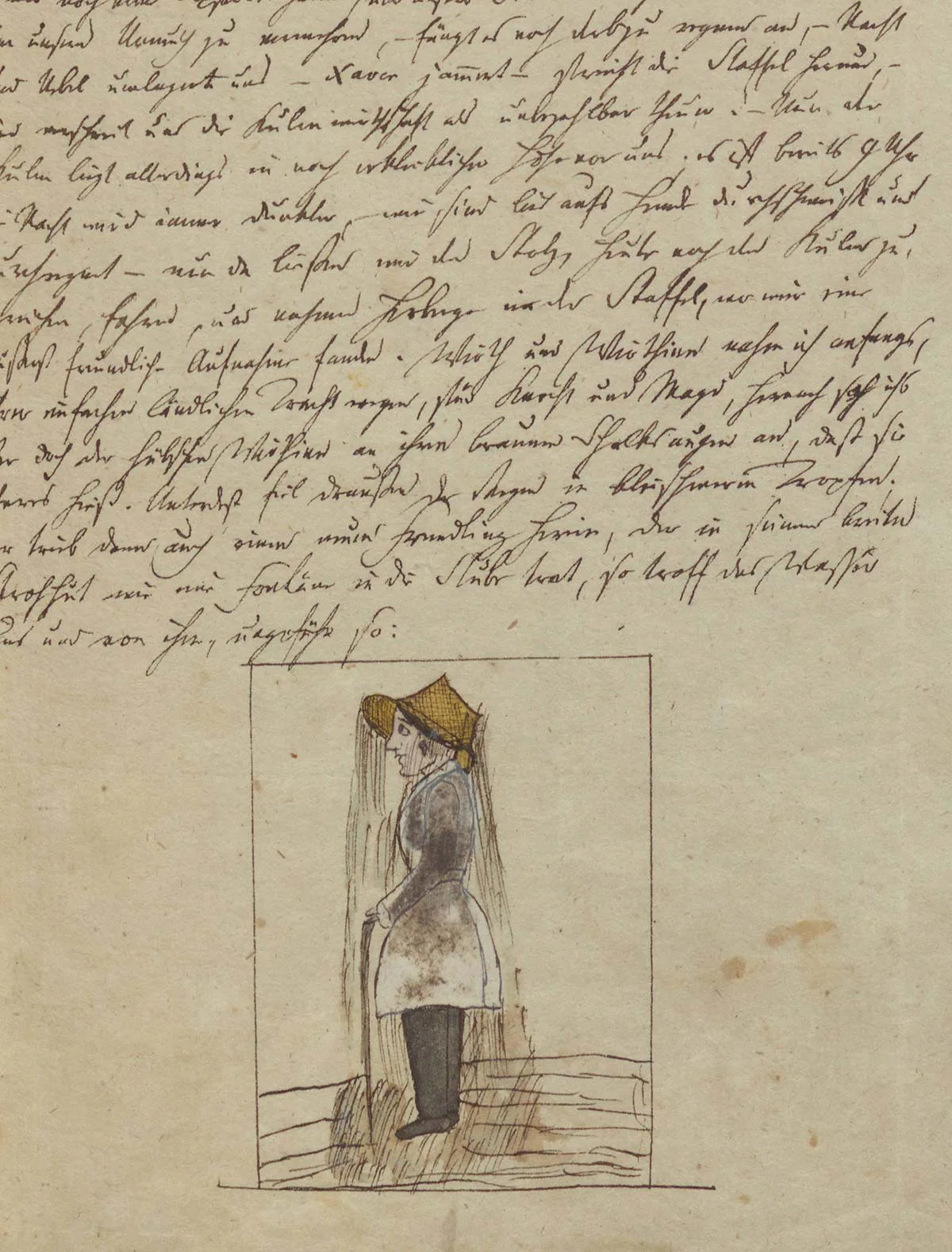

He tells us how in the winter there are only two monks left in the monastery, while in summer there are six to eight. The innkeeper here is called Bürgi – a quiet, rather squat man, while his wife Lisette is a pretty young thing wearing traditional Swiss dress. She had previously lived for some time in Dresden – where she had long been deceived by an unfaithful husband – and now lives happily at the top of the Rigi, although by all accounts she is happier in her waking hours than at night. I initially mistook the waitress here – a pretty young girl – for the landlady, to which she replied, blushing: “Forgive me, sir, but I’m not the boss”. – Now an Englishman appears with his wife. They have been here for three days waiting for good weather; he has a proper ruddy English complexion and wears a long Mackintosh with silver coin-like buttons and carries a guidebook.”

I’m filled with terror – what will Mylady do? She smiles and returns to the inn with the guide. Finally, after half an hour, Mylord crawls back up. I couldn’t wait to see their joy at being reunited. I accompany him into the building, where Mylady is sitting on the sofa, reading. Mylord comes in, no greetings, no questions. No one looks at each other. The guide shakes his head. What strange people, the English!

Like everywhere in Switzerland, the coffee here is bad, but the milk is better, which is why coffee is always served so milky. The library at the summit comprises most of the best French and German classics of fiction.”

Why the Jungfrau is called Madame Meyer

Next to us stands the Englishman, the wide flaps of his fur cap folded down, map in hand, and next to him the guide, who has to accompany the Englishman everywhere to explain everything as he gesticulates into the air with his umbrella. Mylady stands nearby, shivering with cold. She clutches at her hat with both hands, pacing back and forth as a strong, cold wind blows, while carrying her alpenstock under her arm.”

The excitement about seeing the sunrise got me out of bed at 3 o’clock the next morning. Before long, Mylord and Mylady who – as we discovered last night are actually American English, appeared with their guide, chatting away cheerfully as they walked, despite the cold. I can’t overstate the beauty of the scene that awaited us: the sun appeared in all its glory, its rays illuminating the silver white Alps of the Bernese Highlands. The sublime Jungfrau and its vast neighbours looked calmly into the sun’s face until their snowy cheeks blushed with shame. How fortunate we are – more so than Mylord, who despite the guide’s explanations, is still trying to make out the Jungfrau.”