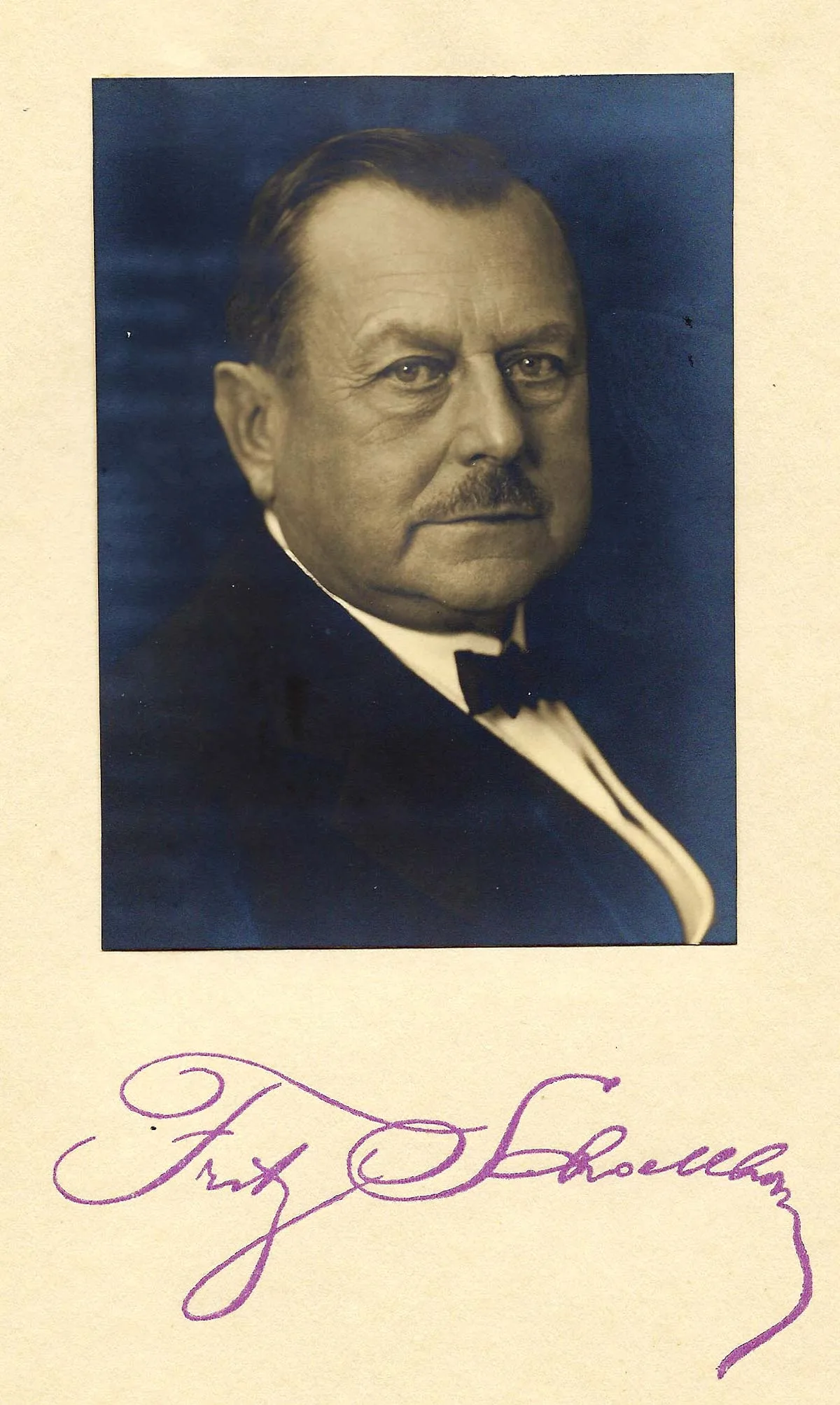

The pioneering brewer with an honorary doctorate

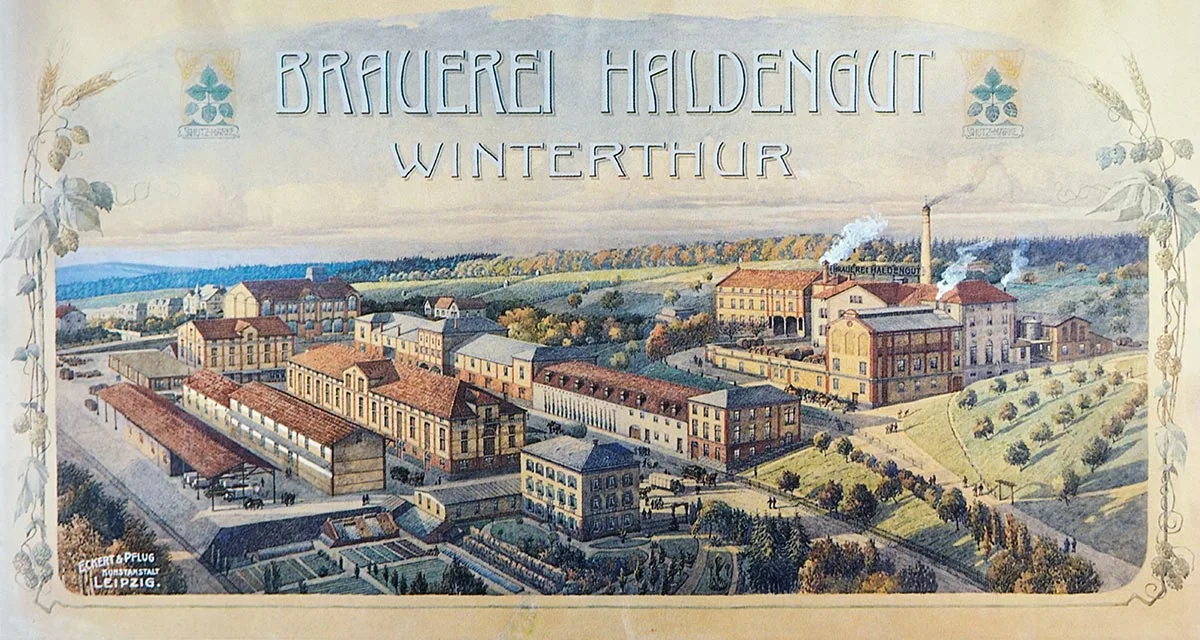

Fritz Schoellhorn was a successful businessman, brewer and owner of Haldengut Brewery in Winterthur. He was even awarded an honorary doctorate from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH) for his technical and scientific achievements.