Beer as a mirror

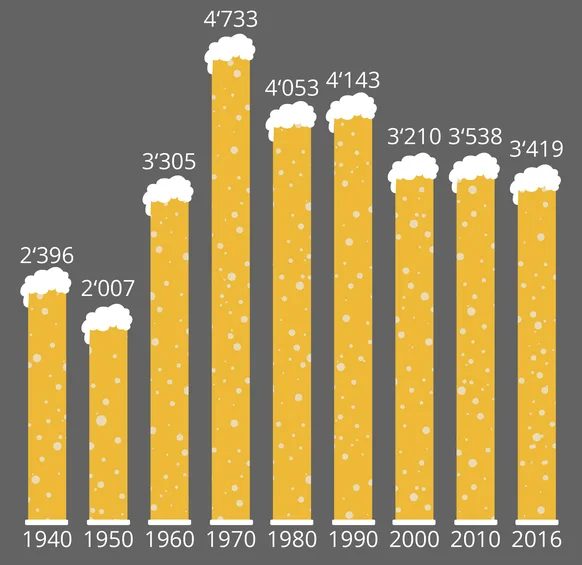

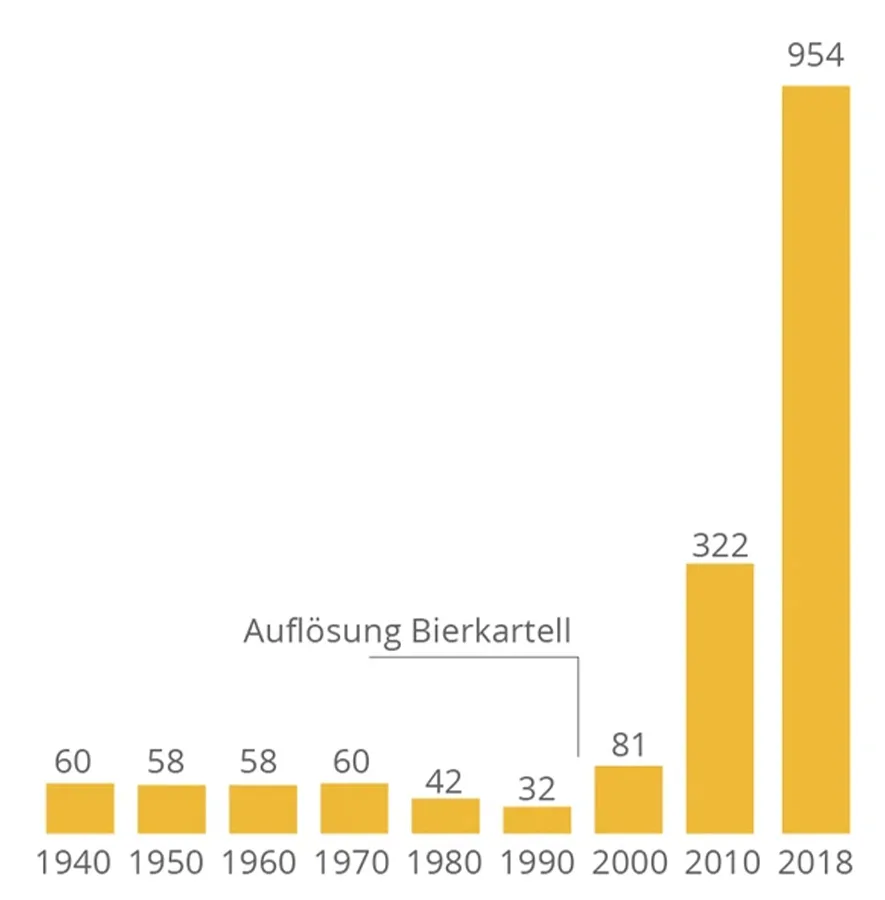

With the fall of the beer cartel, Switzerland’s breweries entered a new era. The way was clear for foreign corporations, alternative business models and smaller competitors. This phenomenon reflects the history of an entire national economy.

Lost protection

Survival strategies

Localness, for the few