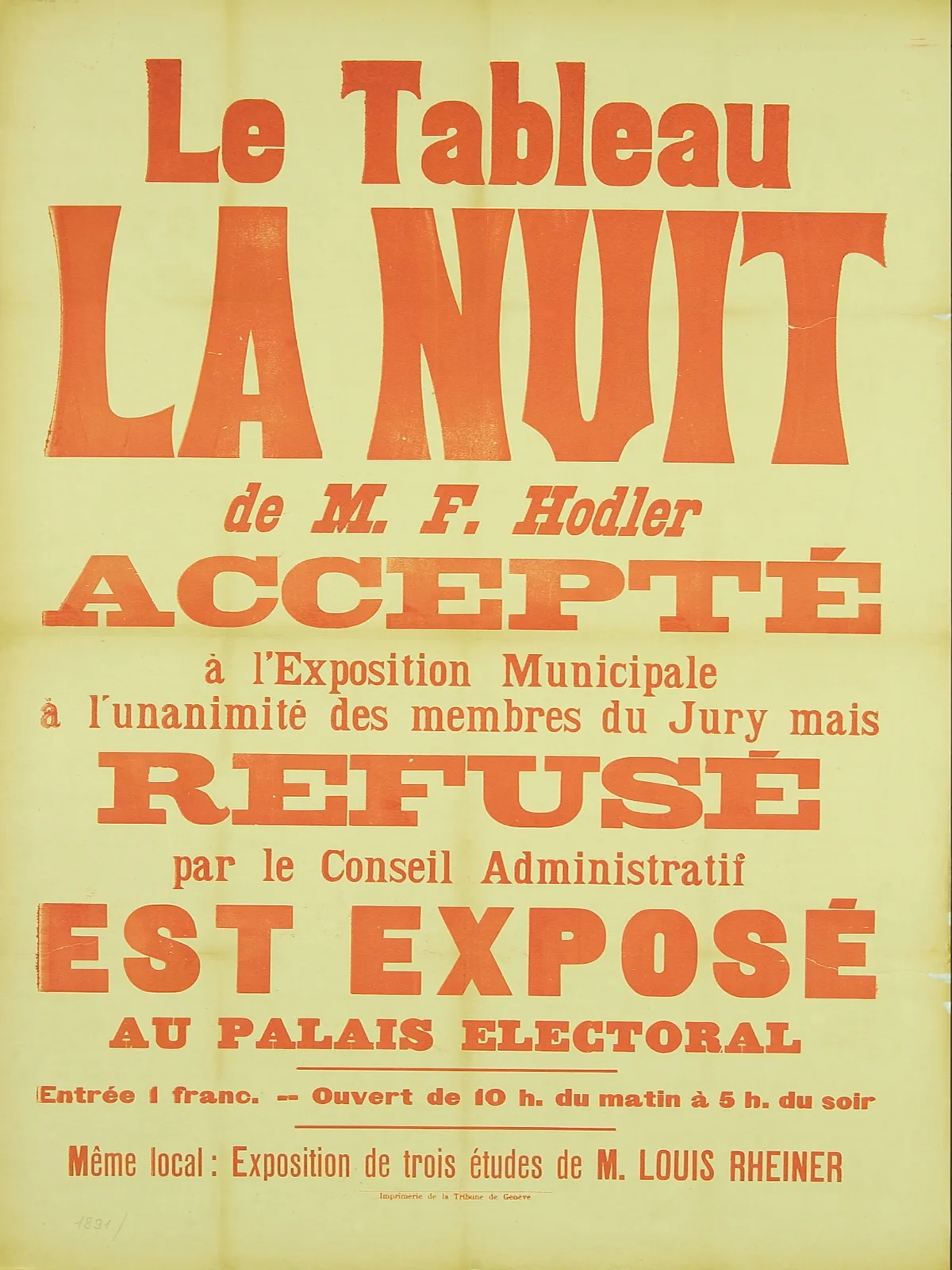

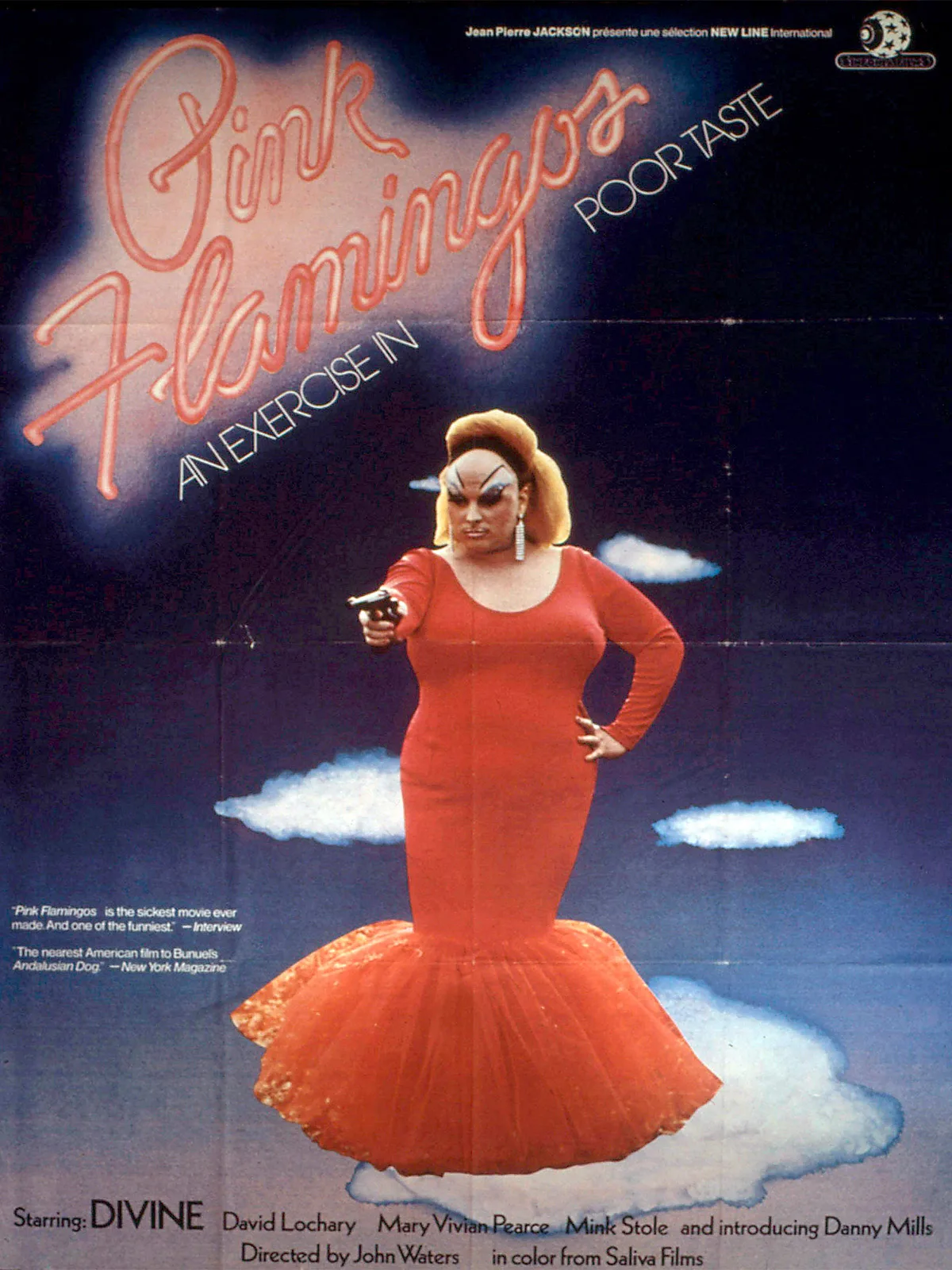

The right to a free press, free speech and artistic expression

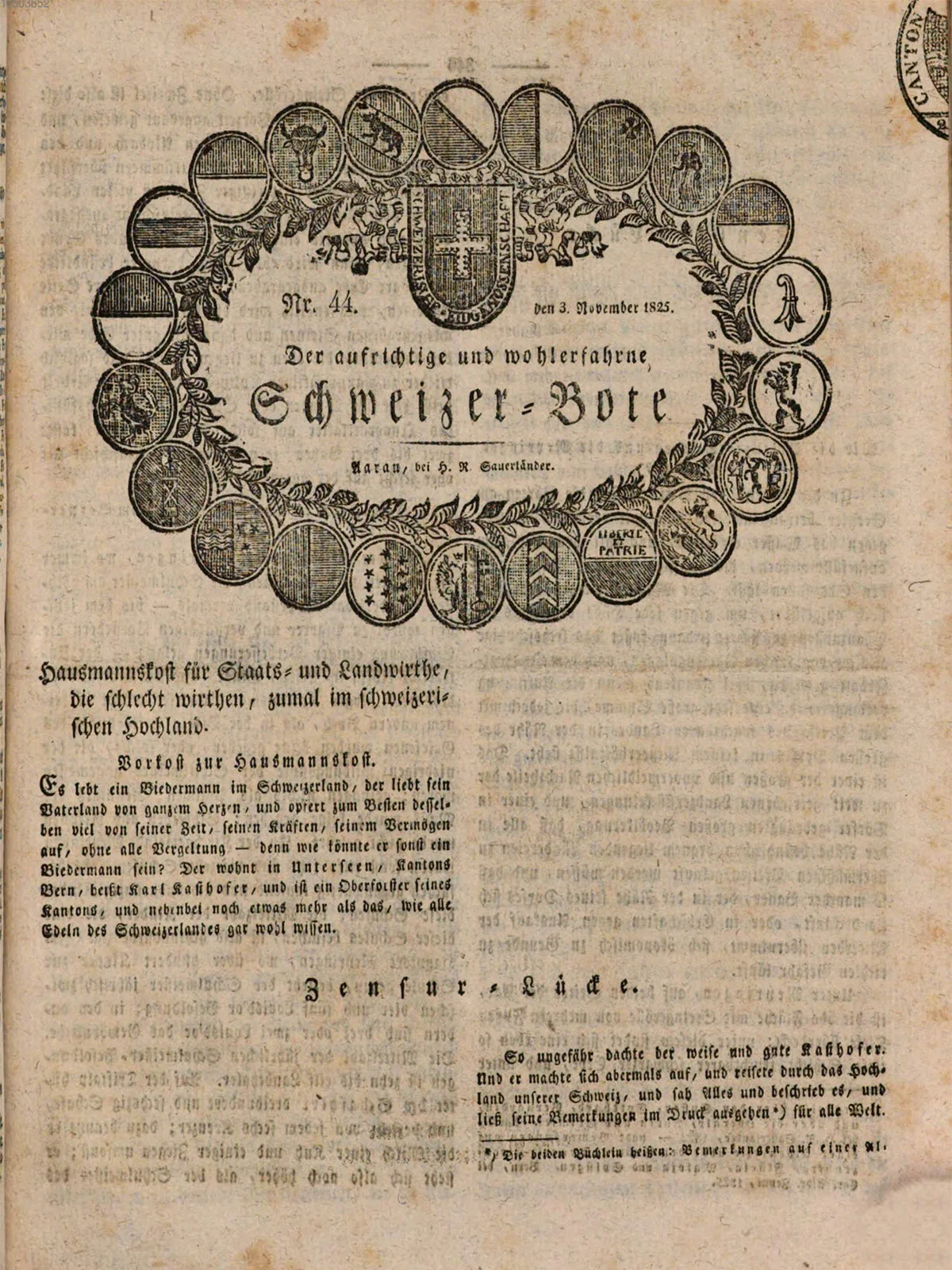

Freedom of expression is sometimes described as oxygen to democracy. Freedom of the press has been enshrined in the Federal Constitution since 1848. However, the right to free speech and artistic expression were only recognised as fundamental rights in the 20th century.

Every person has the right freely to form, express, and impart their opinions.