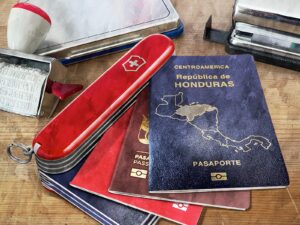

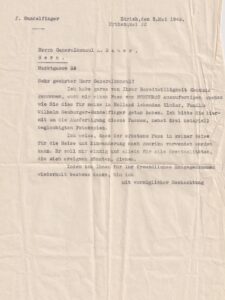

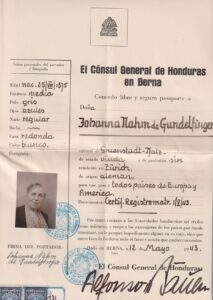

A passport for every eventuality

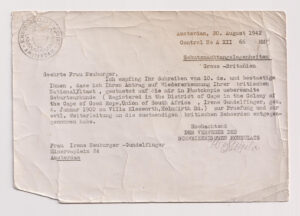

In the 1940s, Jews in Europe found themselves in increasing danger. This situation benefited a number of individuals who issued false passports for exotic countries such as Honduras and Paraguay.

“My heartfelt thanks go to Dina Wyler and her family (Winterthur / Zurich) for the items on loan and for the information.”

Naomi Lubrich

Anne Frank and Switzerland

The diary of Anne Frank is world famous. It’s less well known that the journey to global publication began in Switzerland. Anne, her sister and her mother all died in the Holocaust. Otto Frank was the only family member to survive. After the war, he initially returned to Amsterdam. In the 1950s, he moved in with his sister in Basel. From there, he made it his task to share his daughter’s diary with the world whilst preserving her message on humanity and tolerance for the coming generations.