When sport was a pawn in the Cold War

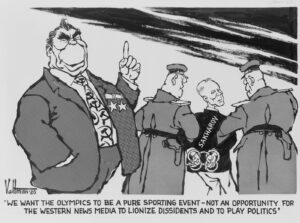

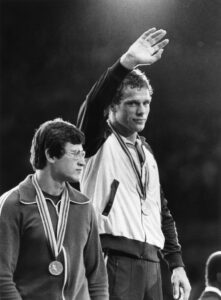

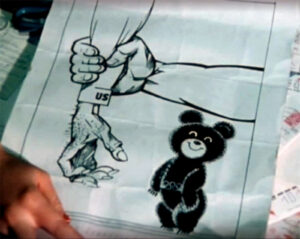

Should athletes participate in events held in countries at war or governed by authoritarian regimes? That is the perennial question. Politicians have no qualms about recommending that their sporting associations impose a boycott. However, sport is per se apolitical. That was the backdrop to the West’s boycotting campaign in the run-up to the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

US President Carter's Speech to Olympic Representatives on 21. March 1980. Jimmy Carter Presidential Library / YouTube

Rundschau programme from the Soviet Union on the Olympic boycott, 8 May 1980. SRF

Swiss Sports History

This text was produced in collaboration with Swiss Sports History, the portal for the history of sports in Switzerland. The portal focuses on education in schools and information for the media, researchers and the general public. Find out more at sportshistory.ch