Switzerland's role in deaf education

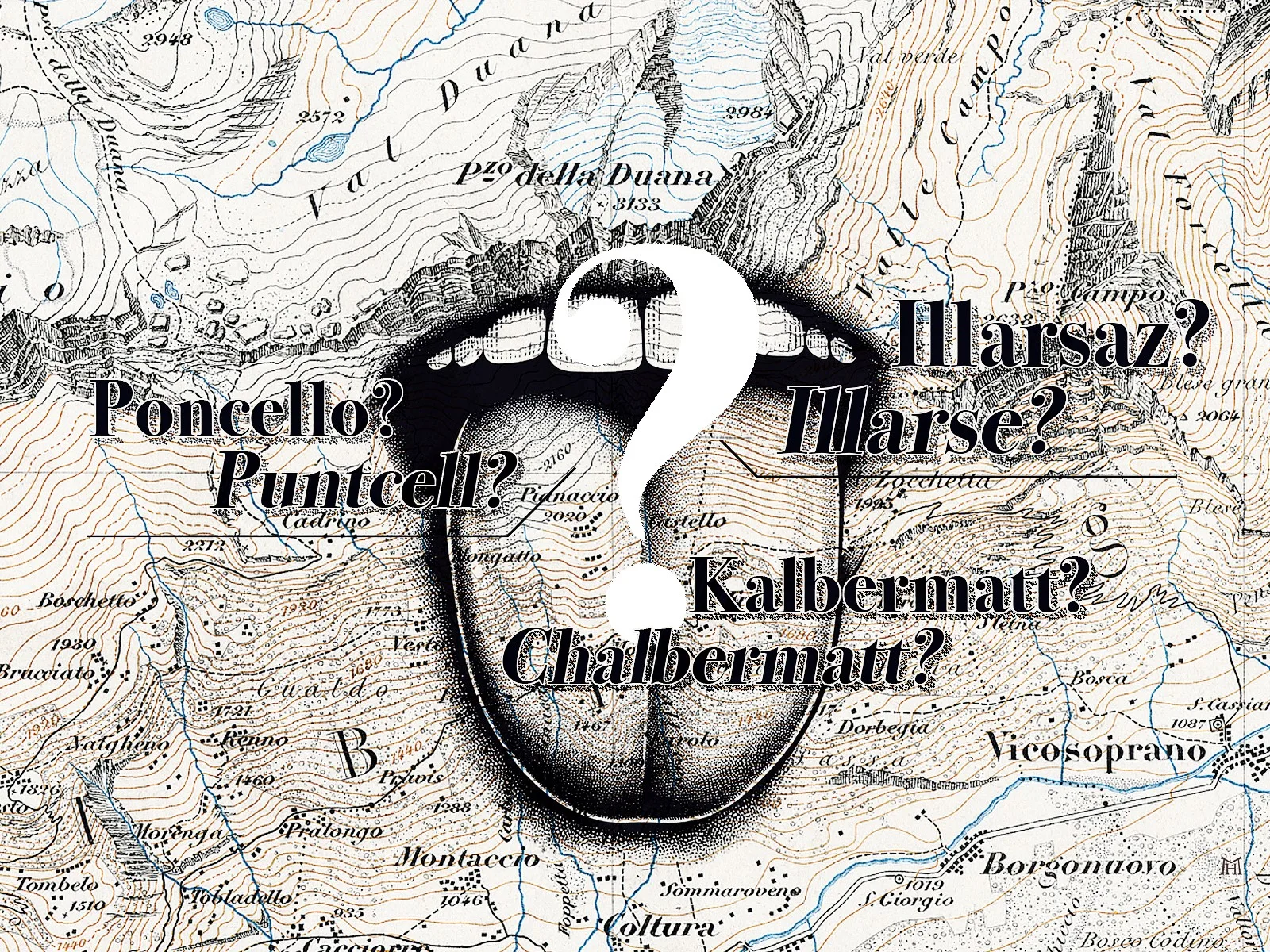

Around 400 years ago, scholars began to address the education of deaf people and developed sign language for the first time. Switzerland played an interesting, complex and perhaps outsized role in this process.

Those who are born deaf all become senseless and incapable of reason.

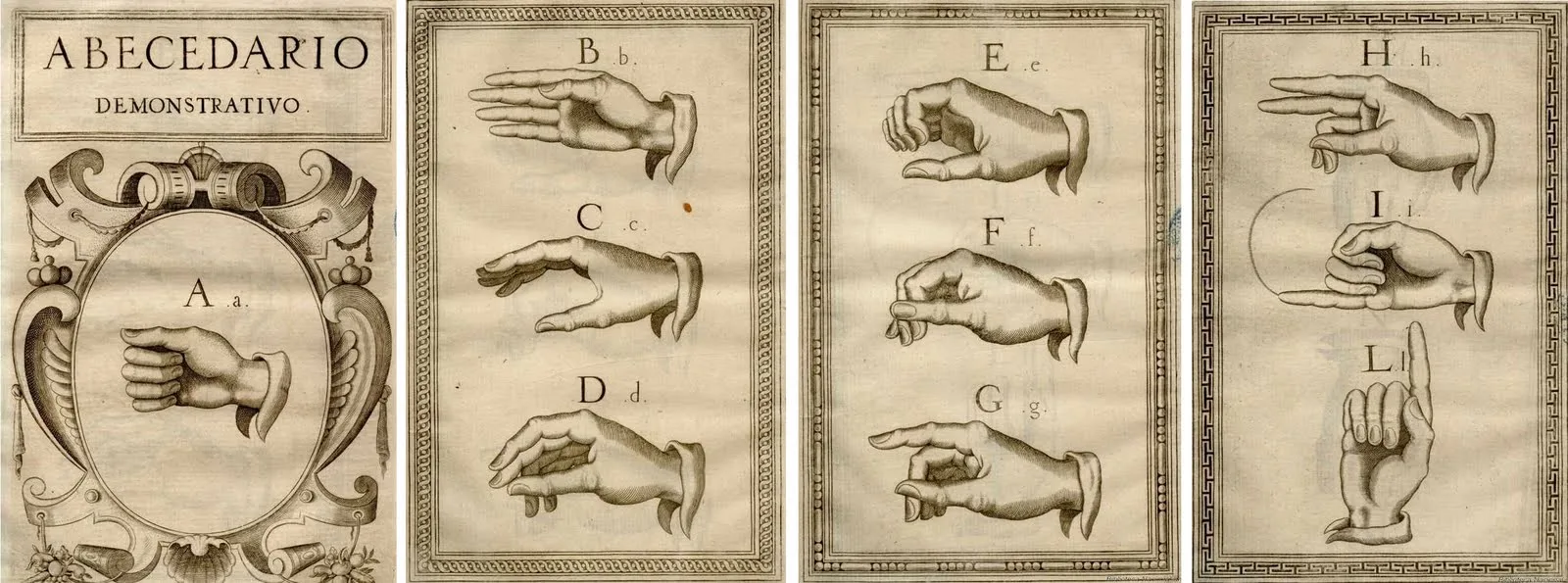

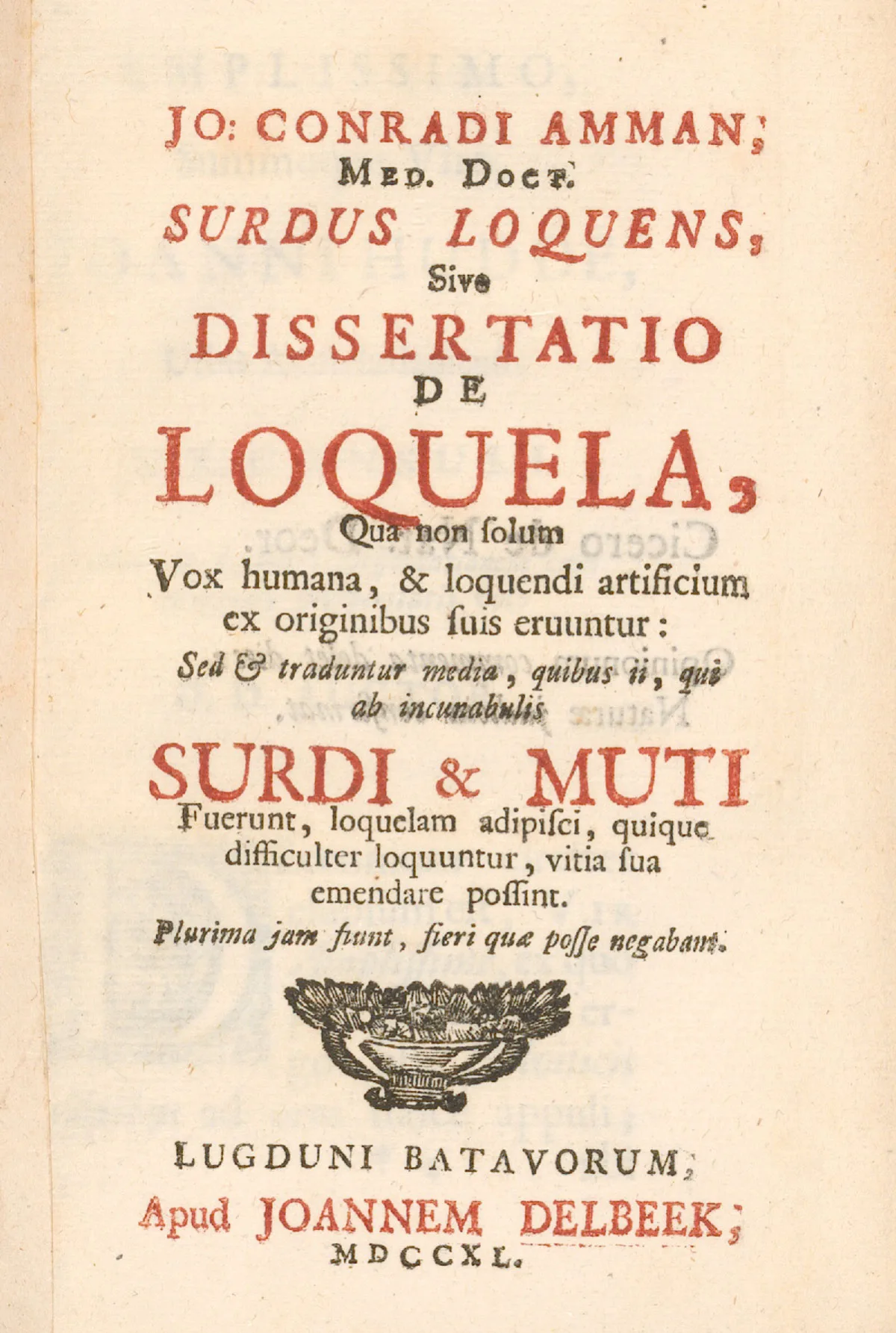

A Swiss Godfather of Deaf Education

I first put his hand on my larynx. Then I put his hand to his own throat and, by means of signs, urged him to produce the same shaking of the larynx that he had perceived in me. It is usually possible to elicit a sound from the student on the first try. Now I teach him to form the mouth opening in such a way that it is necessary for speaking the individual vowels.

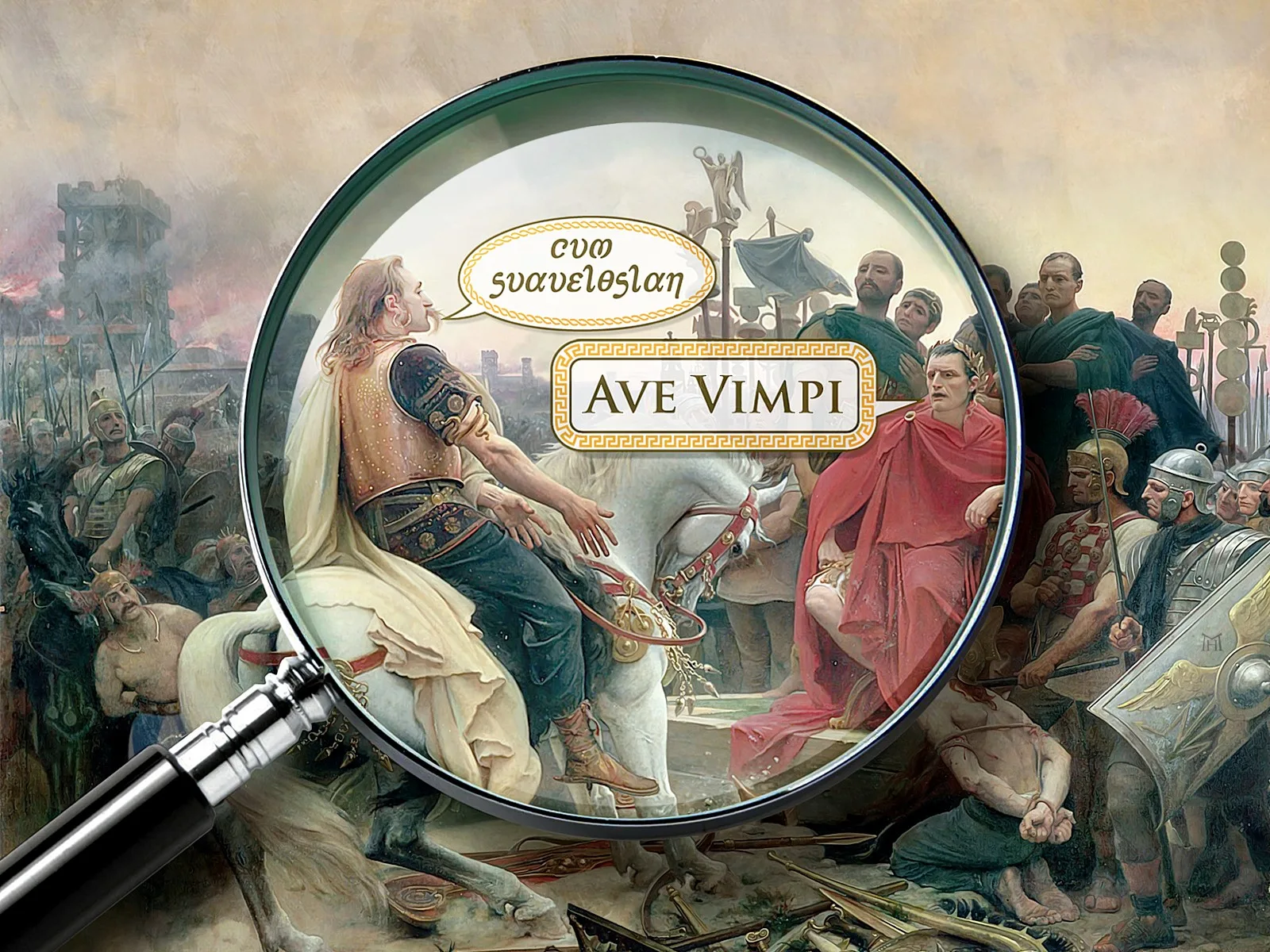

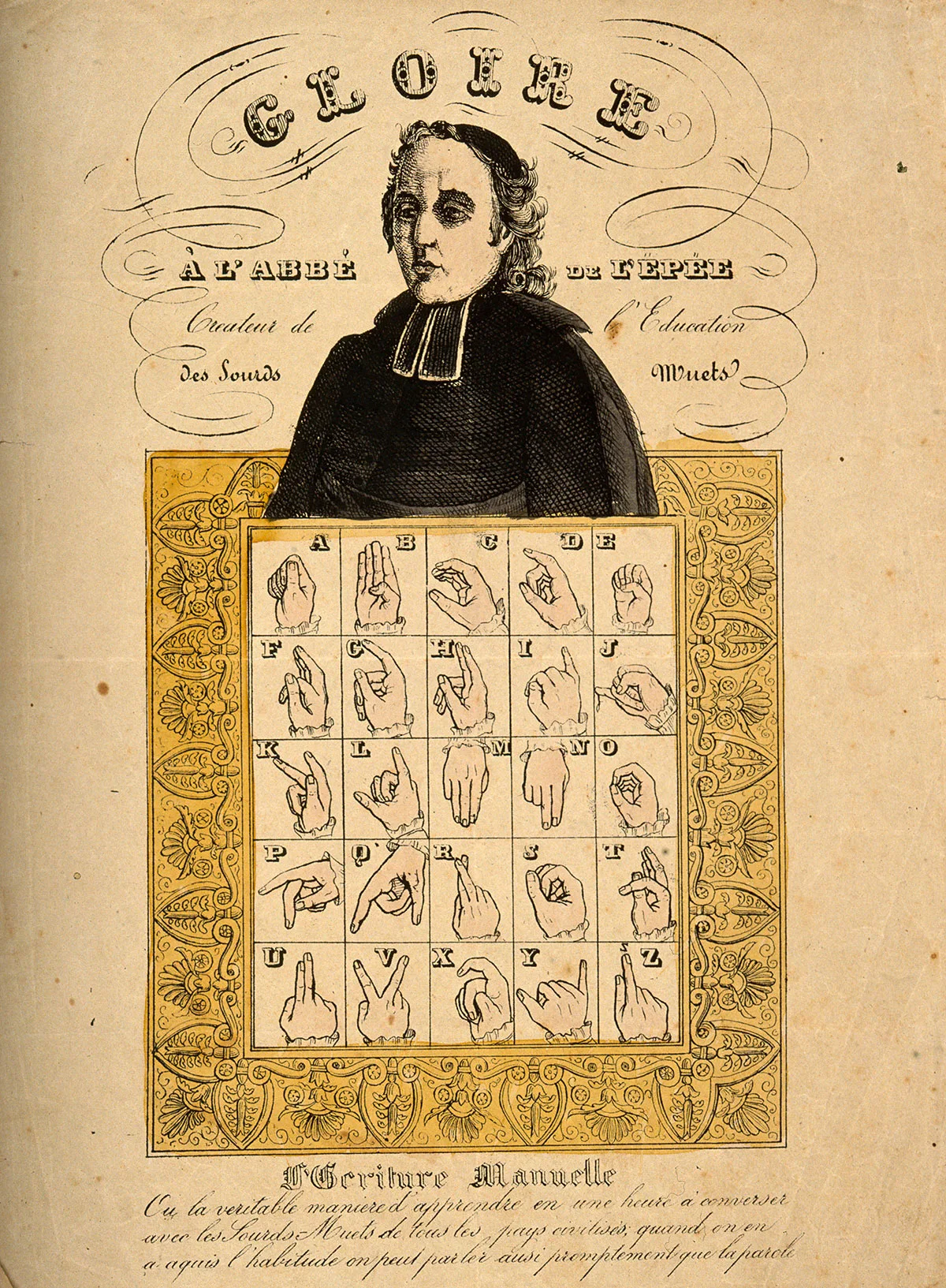

The Debate moves to Paris and Leipzig

Religion and humanity inspire me with such a great interest in a truly destitute class of persons who, though similar to ourselves, are reduced, as it were, to the condition of animals so long as no attempts are made to rescue them from the darkness surrounding them, that I consider it an absolute obligation to make every effort to bring about their release from these shadows.

Zurich scholars settle the dispute