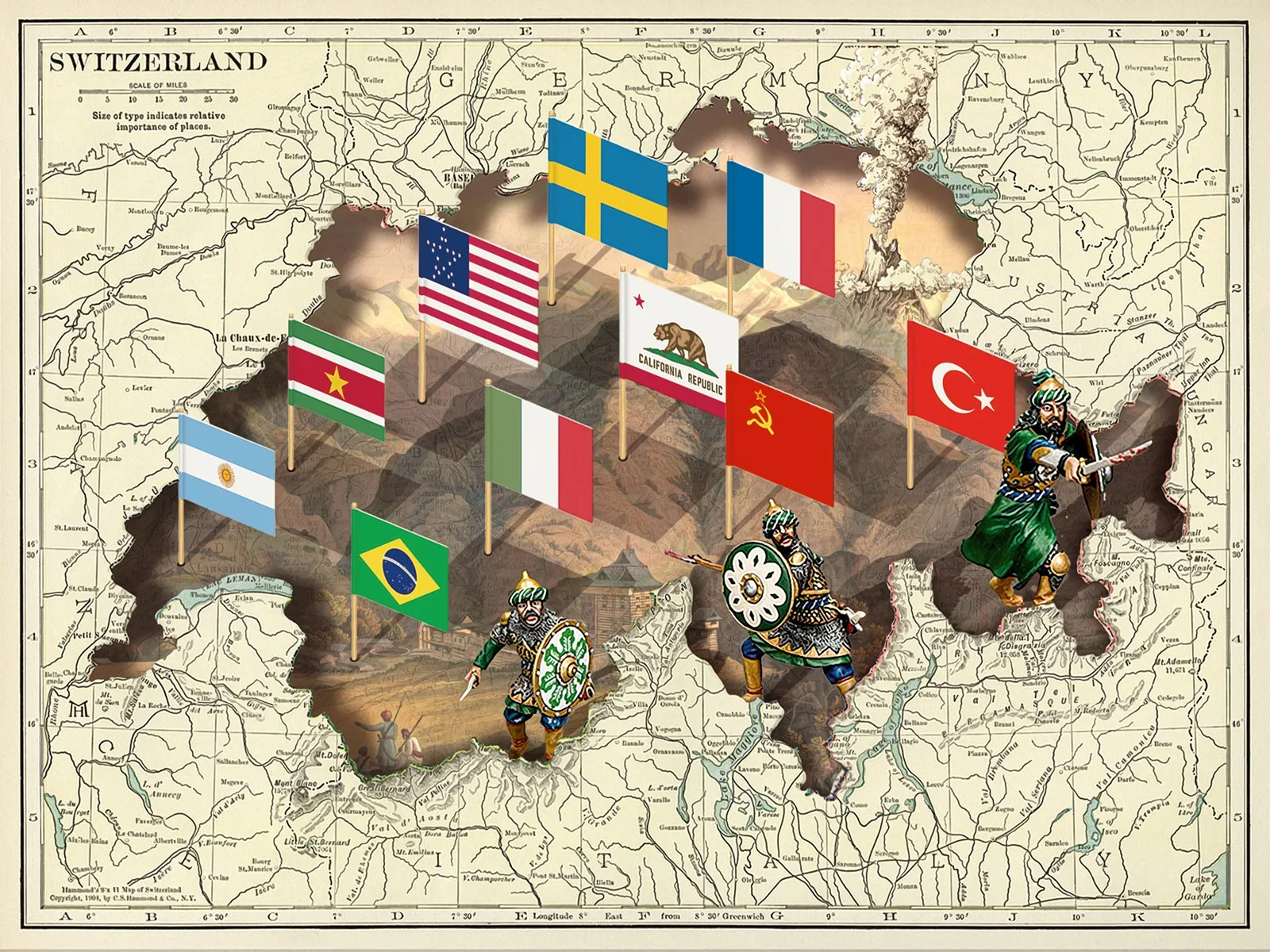

Maps and Switzerland’s linguistic destiny

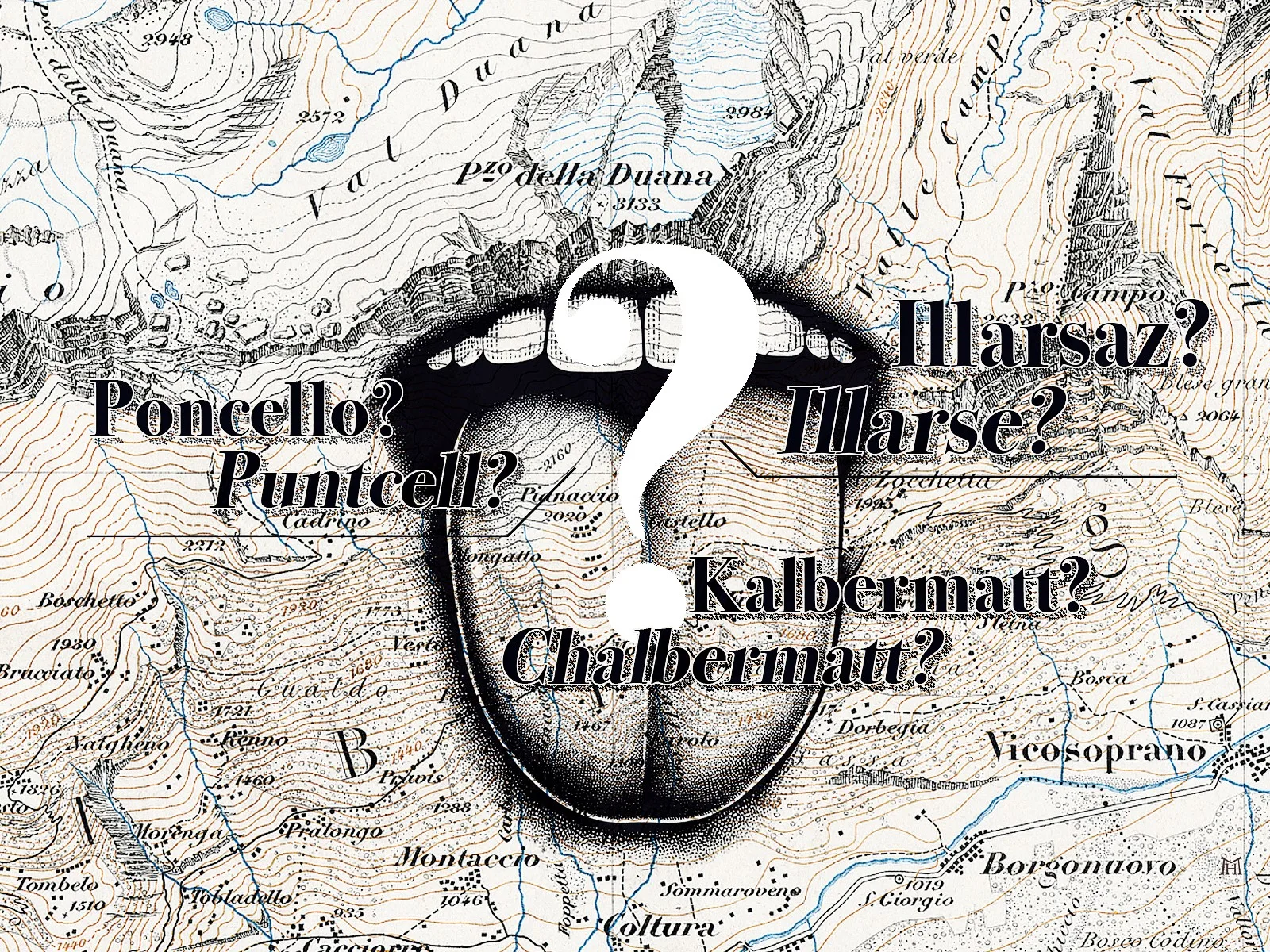

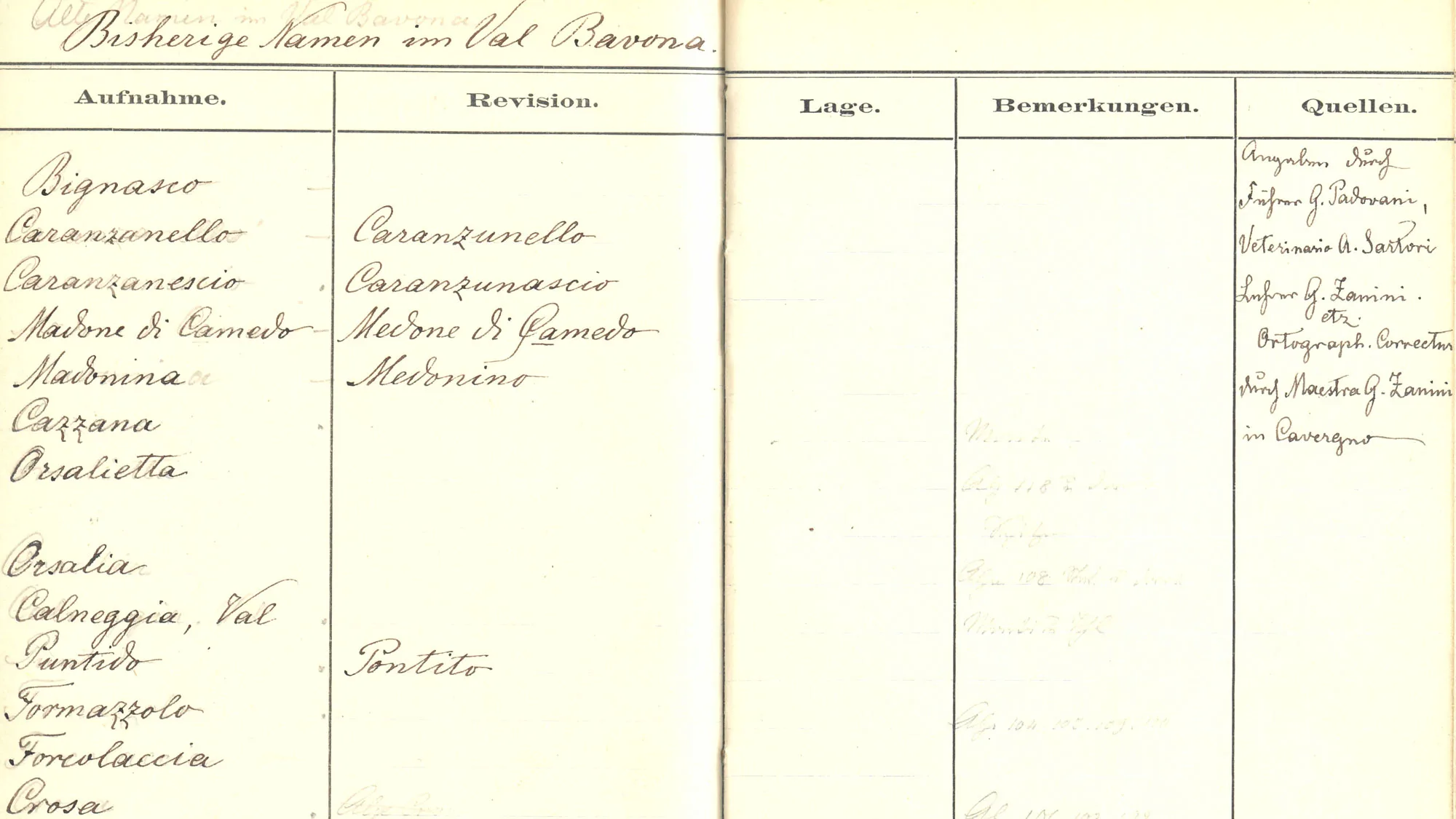

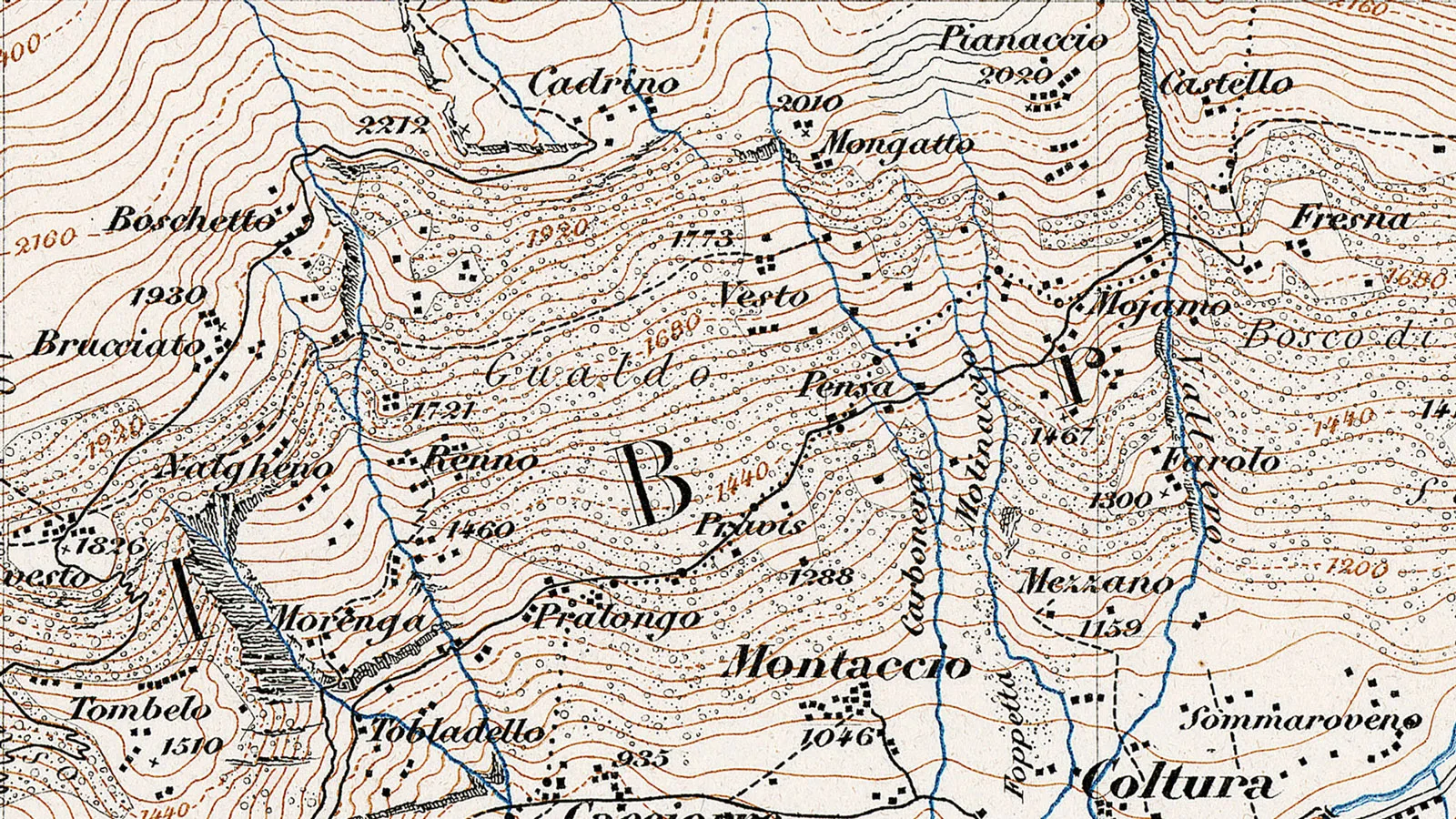

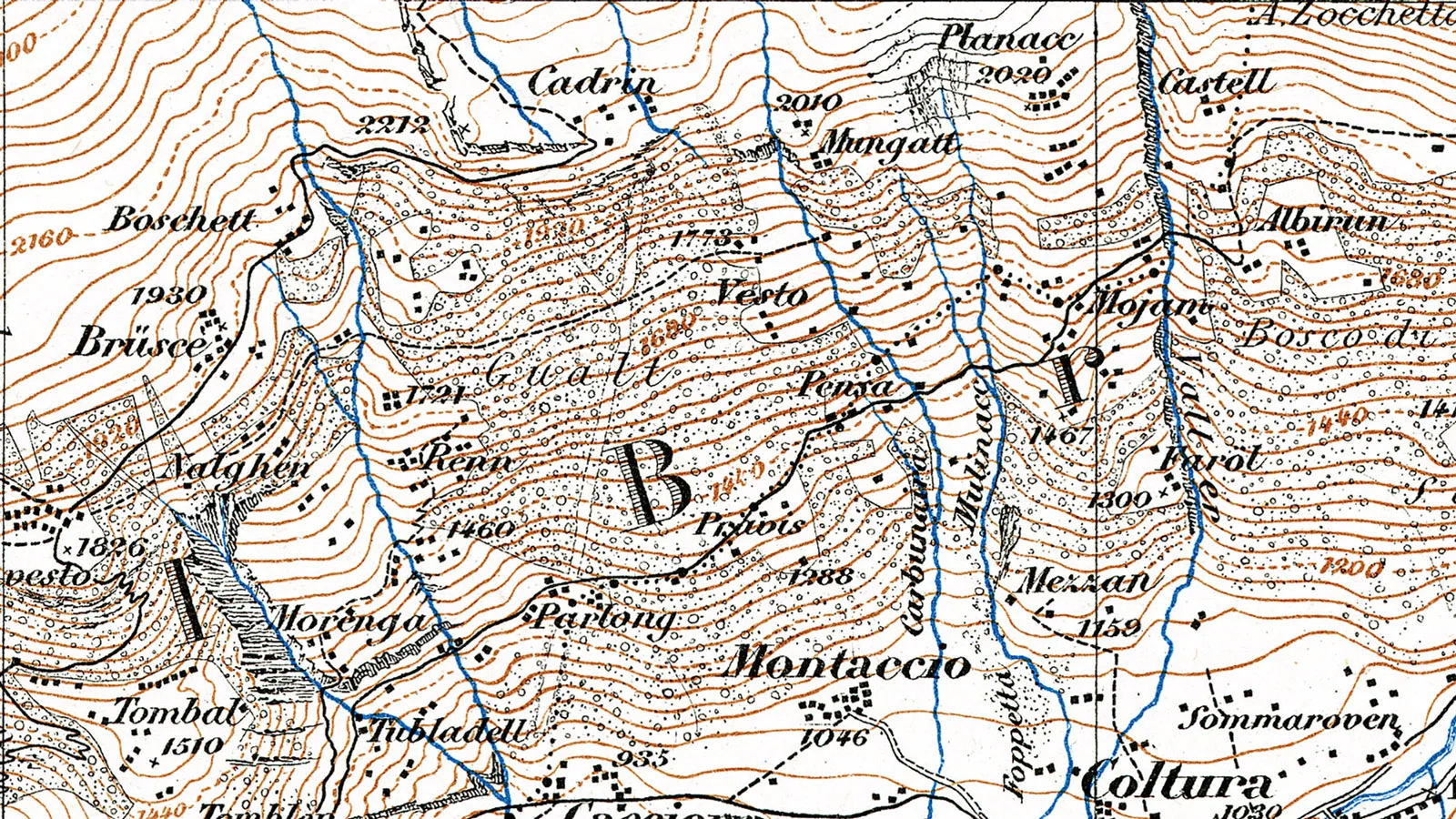

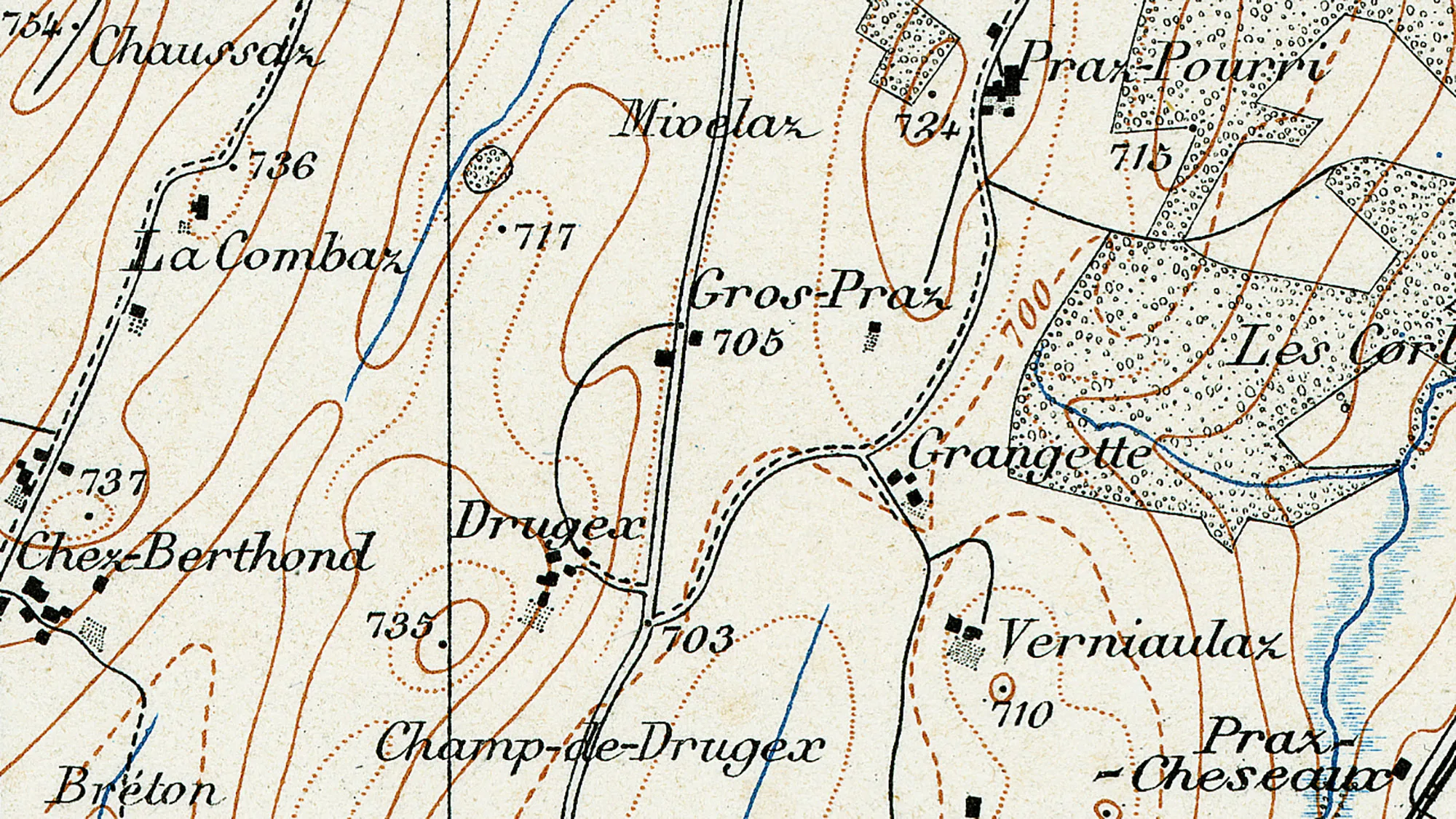

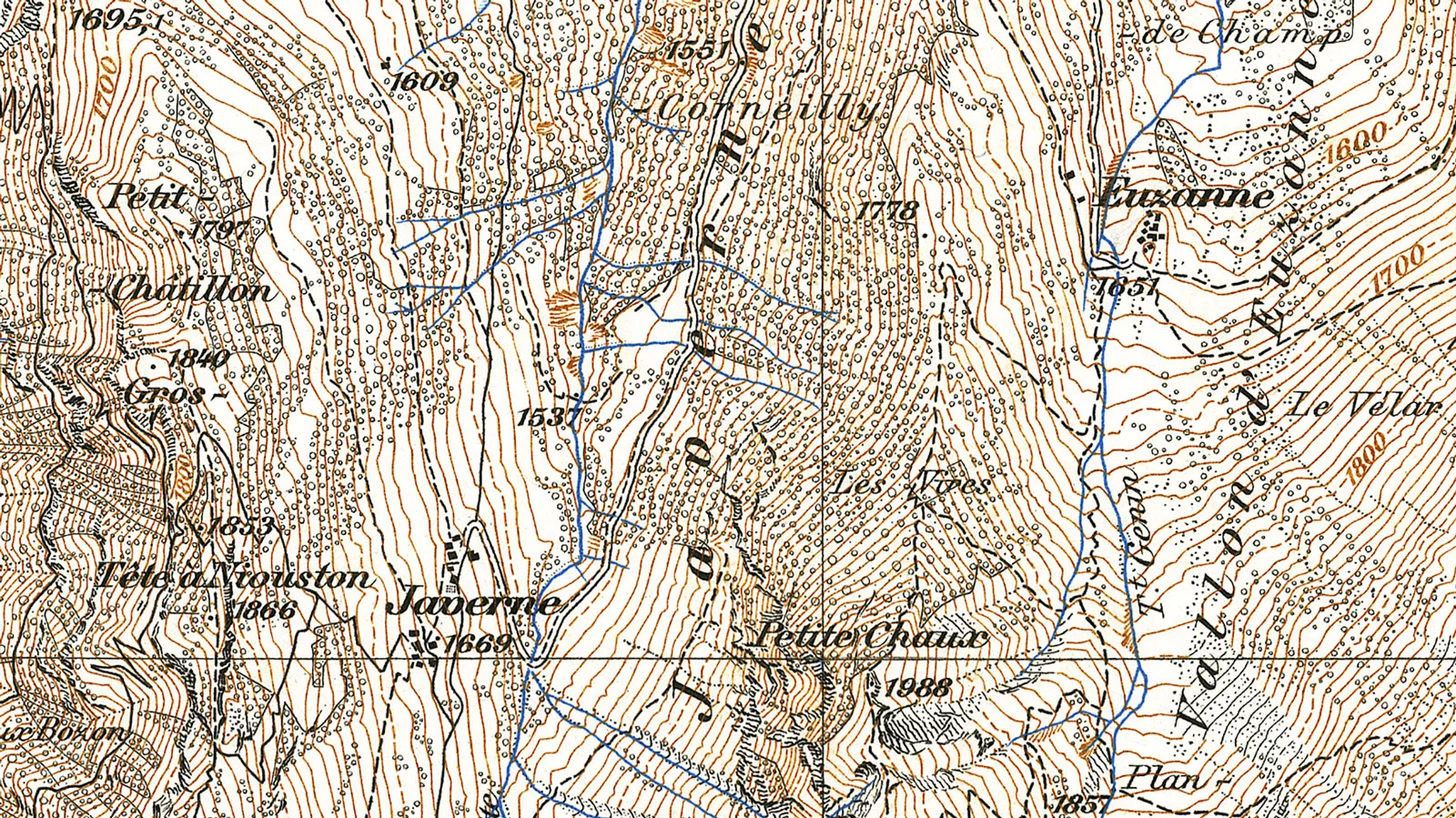

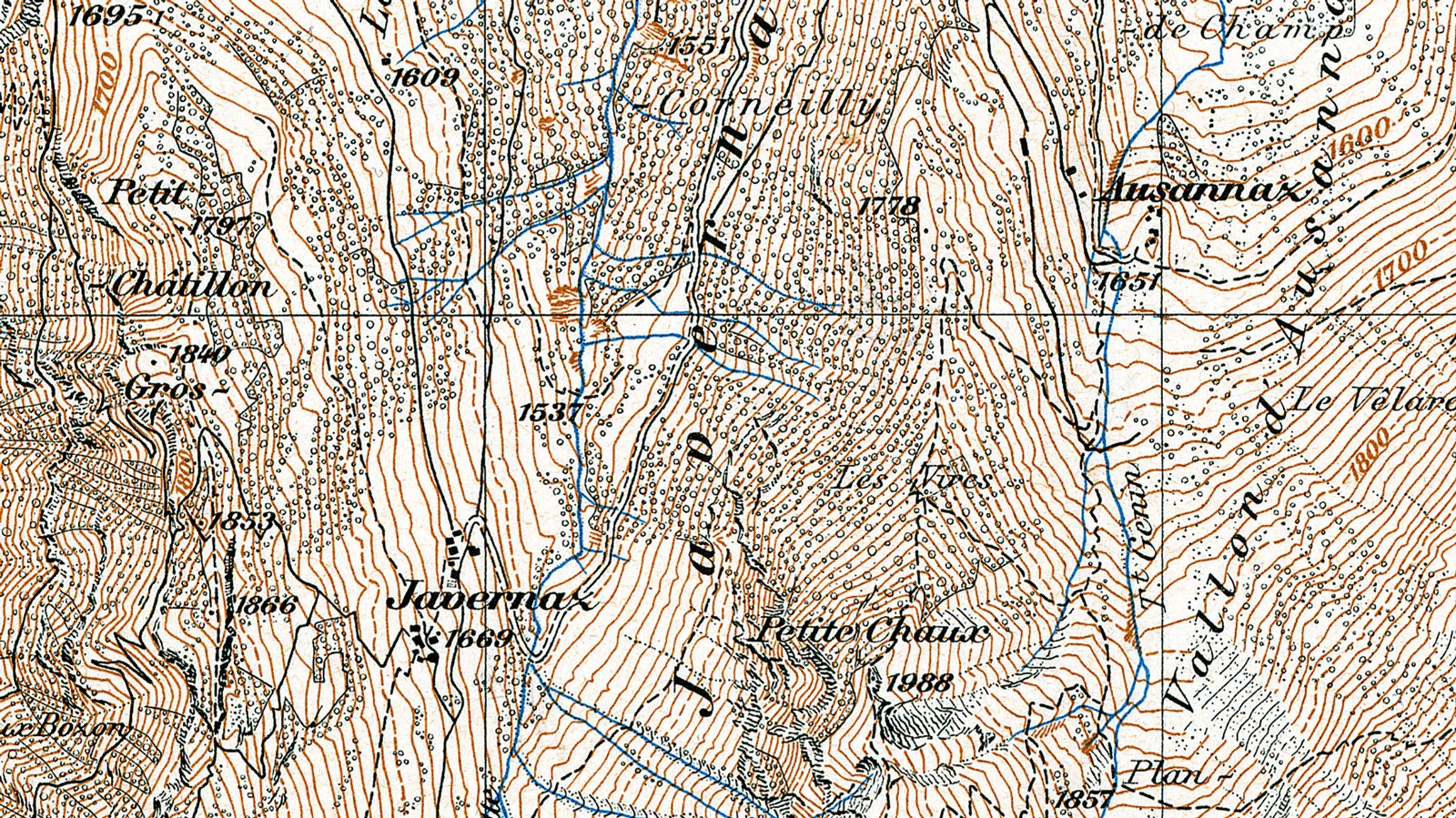

Poncello or Puntcell? Illarsaz or Illarse? Kalbermatt or Chalbermatt? The spelling of place names has frequently been a contentious issue in all parts of Switzerland, particularly when it comes to striking the right balance between standard language and dialect.

swisstopo historic podcast (in German)

Are you interested in the history of place names? You can find out more in the swisstopo historic podcast. Take a listen – available on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or here.

Bargaiot and Italian

Patois and standard French

It is crucially important that dialect place names adopted on maps and in official use are frenchified in moderation, with tact and discretion, but in a generalised and systematic way […]

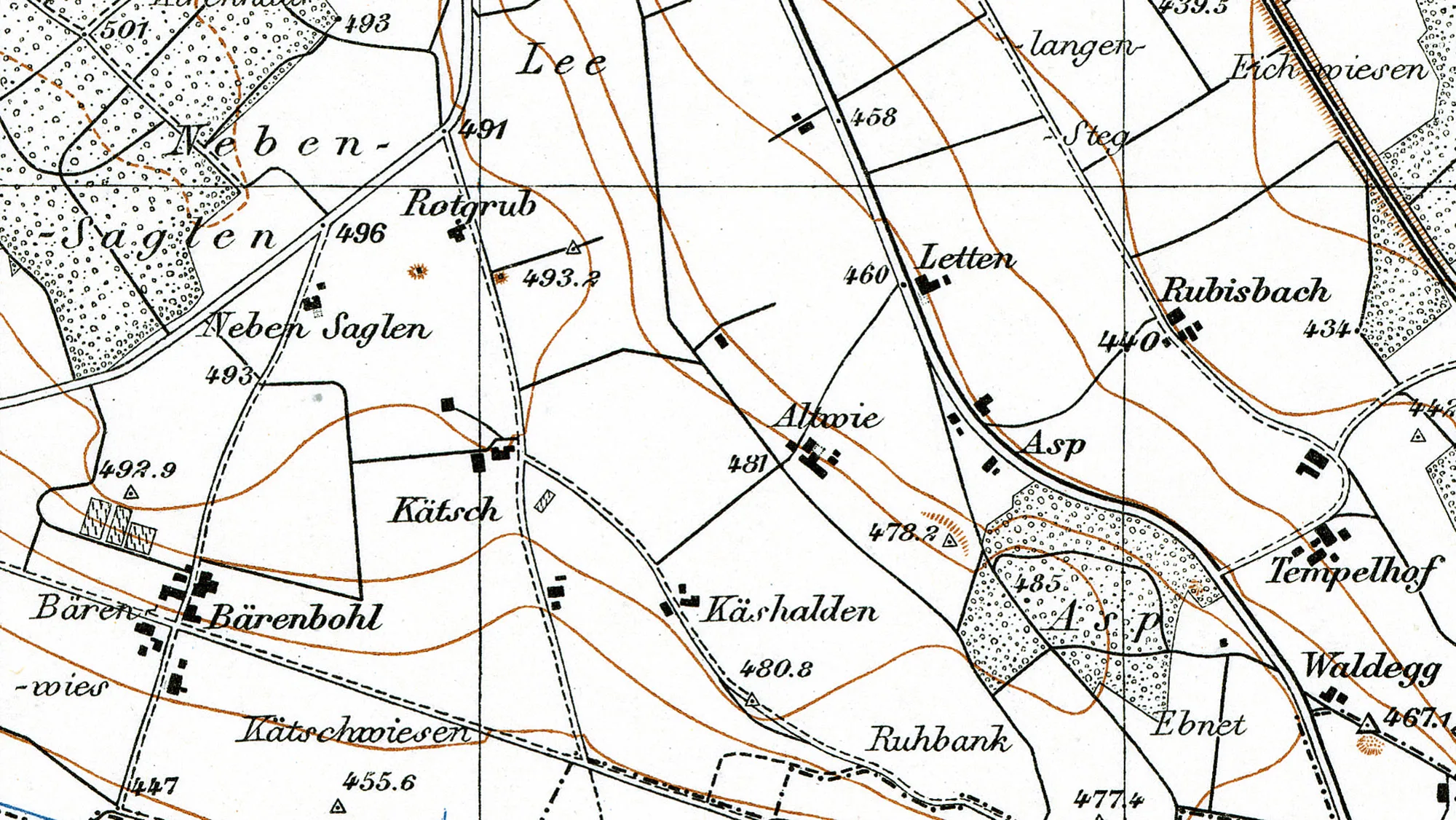

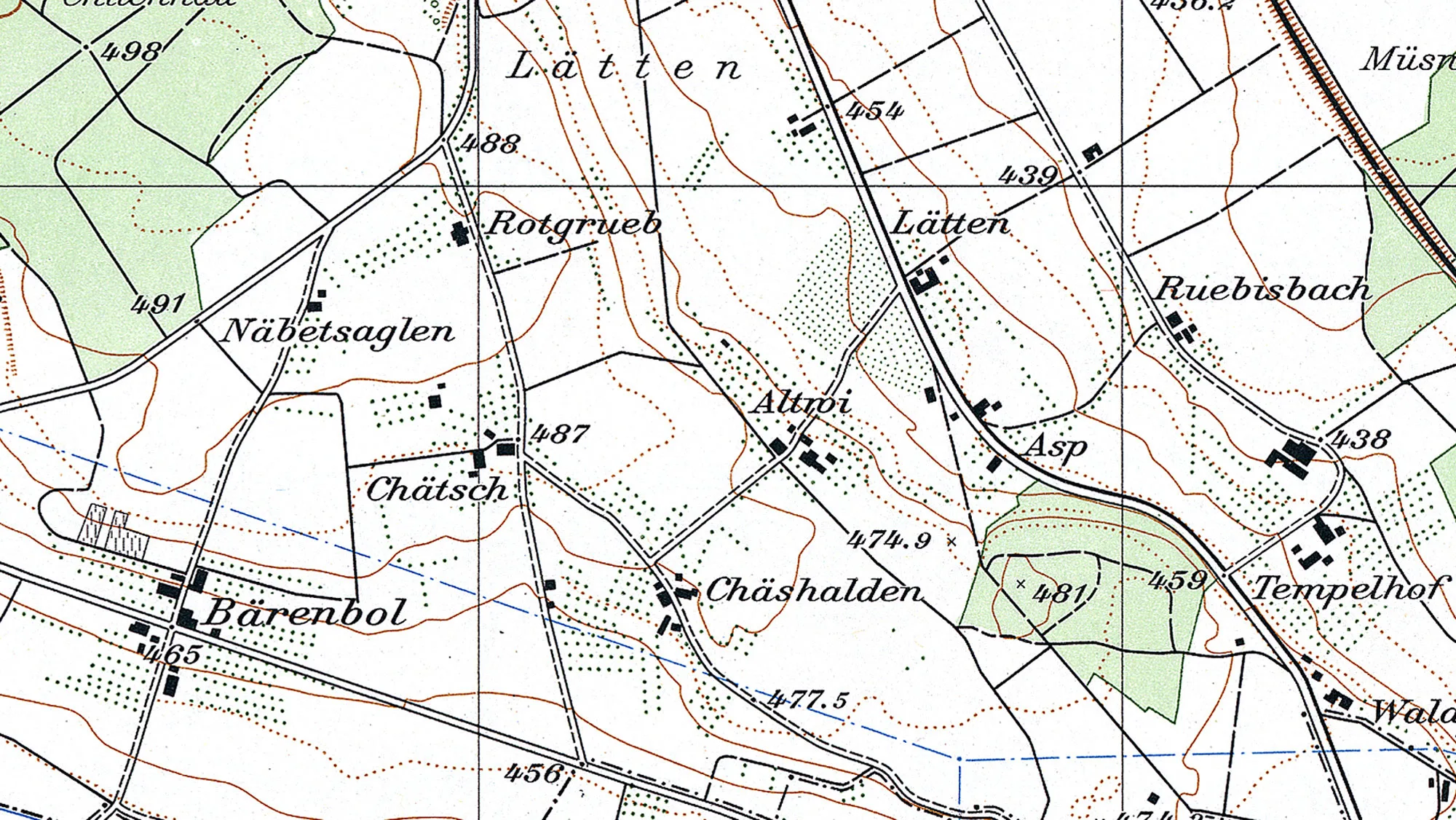

Swiss German and High German

Systematic use of dialect is a pipe dream […]. Our maps reflect Switzerland’s linguistic destiny – the coexistence of dialect and standard language. Is this worth losing sleep over?