Gaulish and Latin in the Swiss Plateau

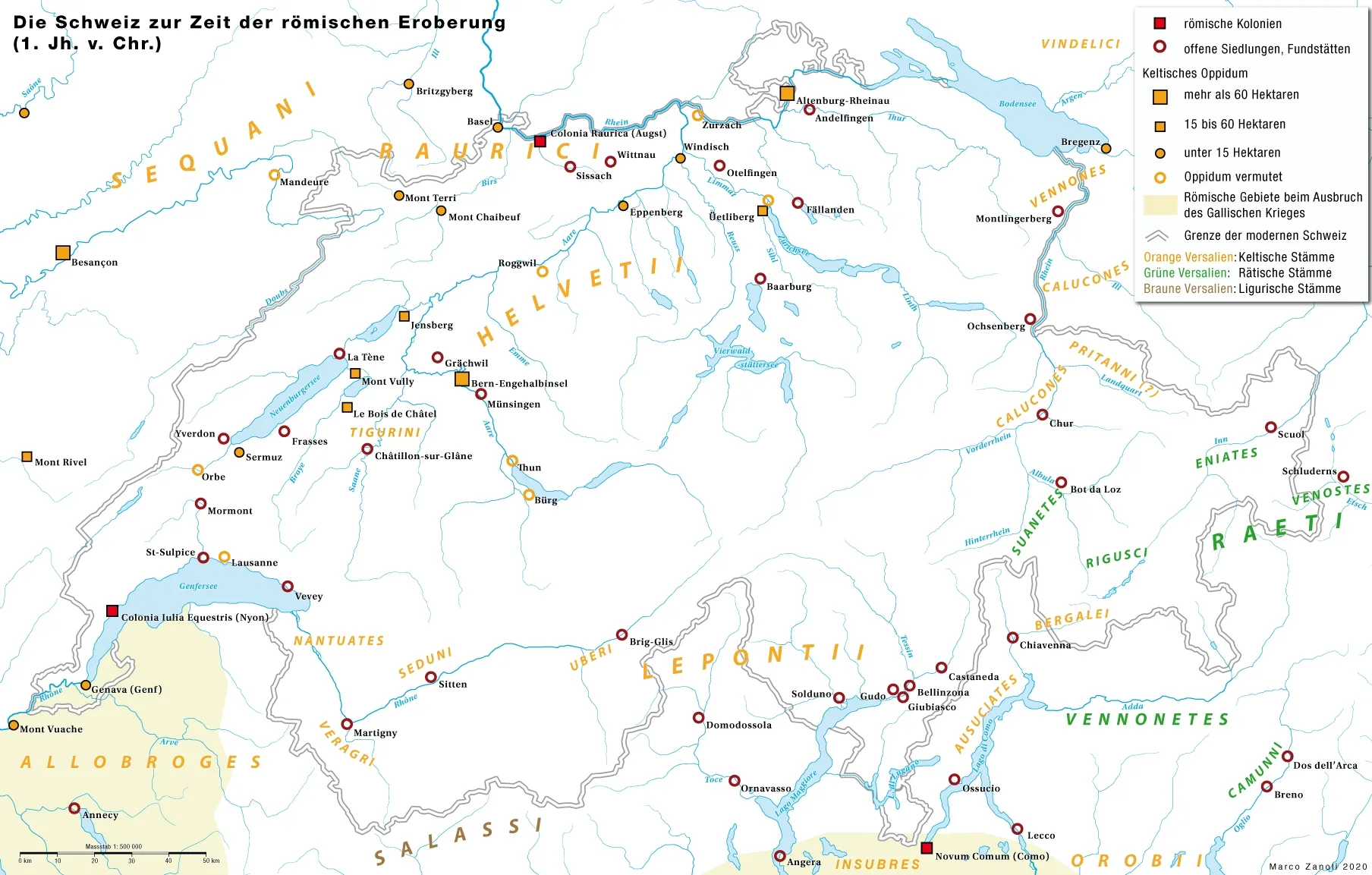

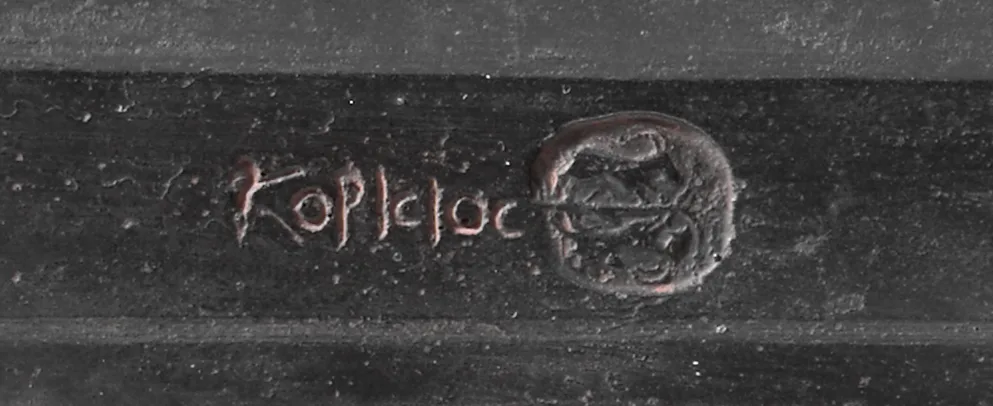

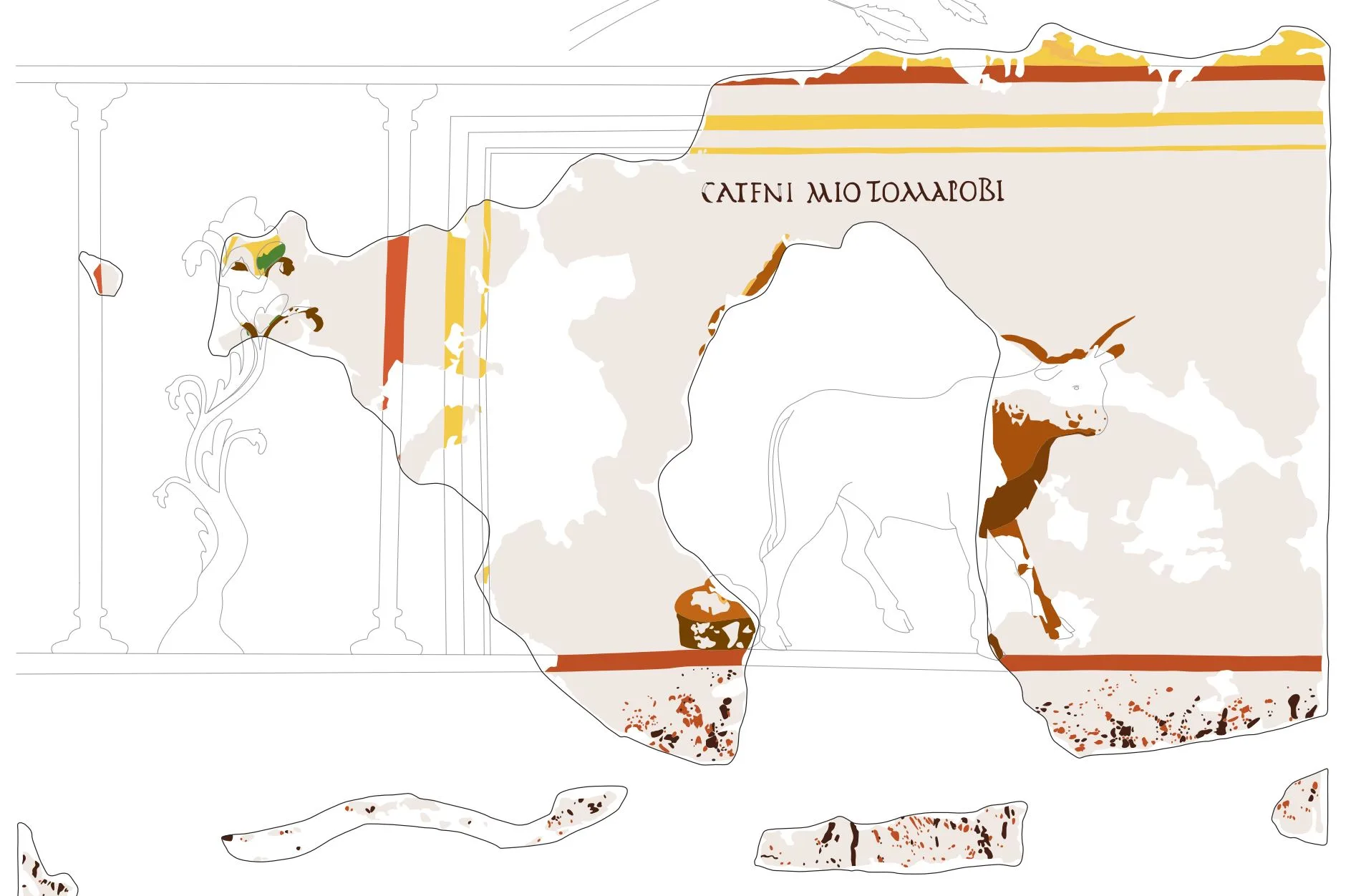

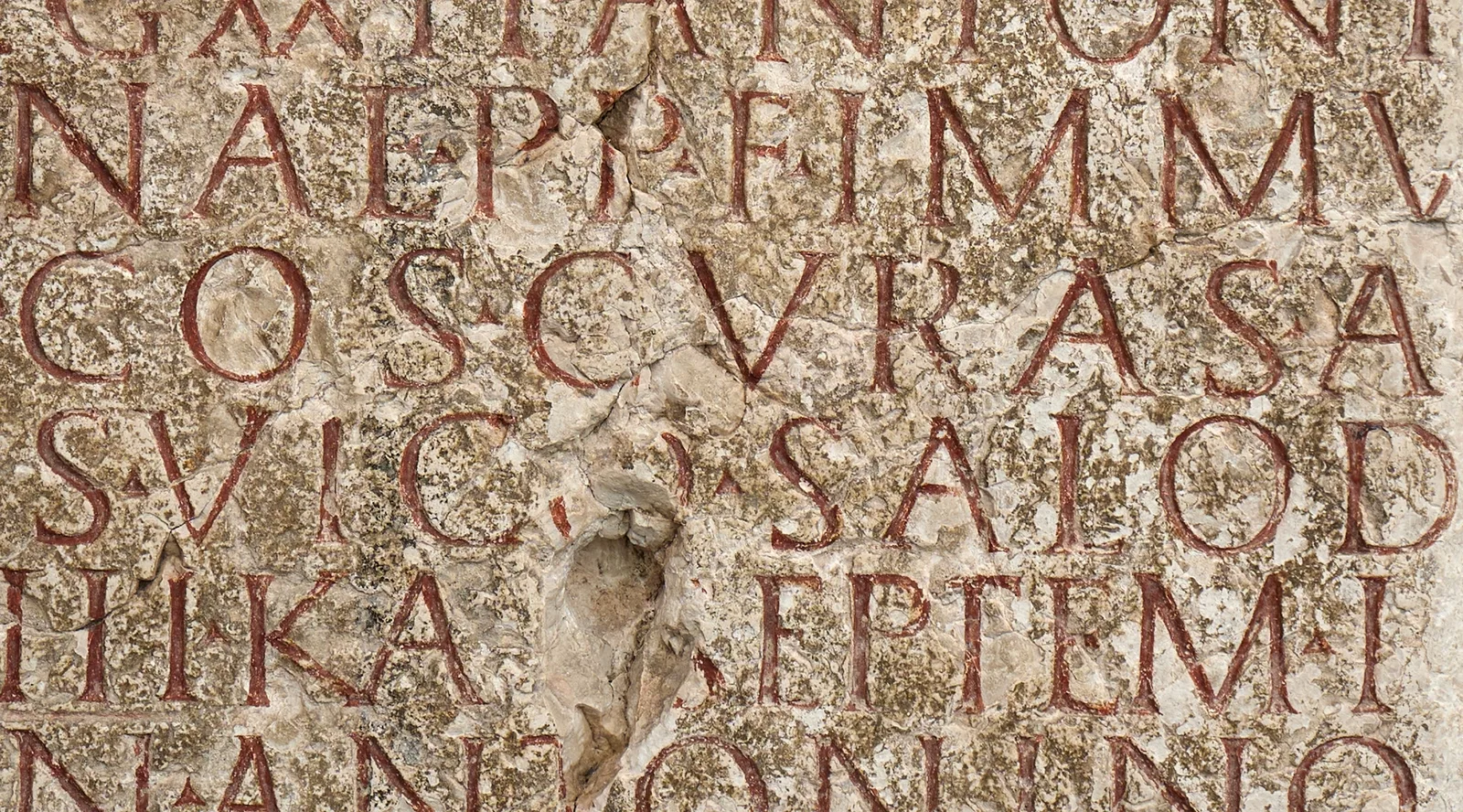

Before the national languages established themselves across the territory of what is now Switzerland, its inhabitants spoke the Gaulish language, which later gave way to Latin. Inscriptions offer small insights into the language culture some 1800 years ago.

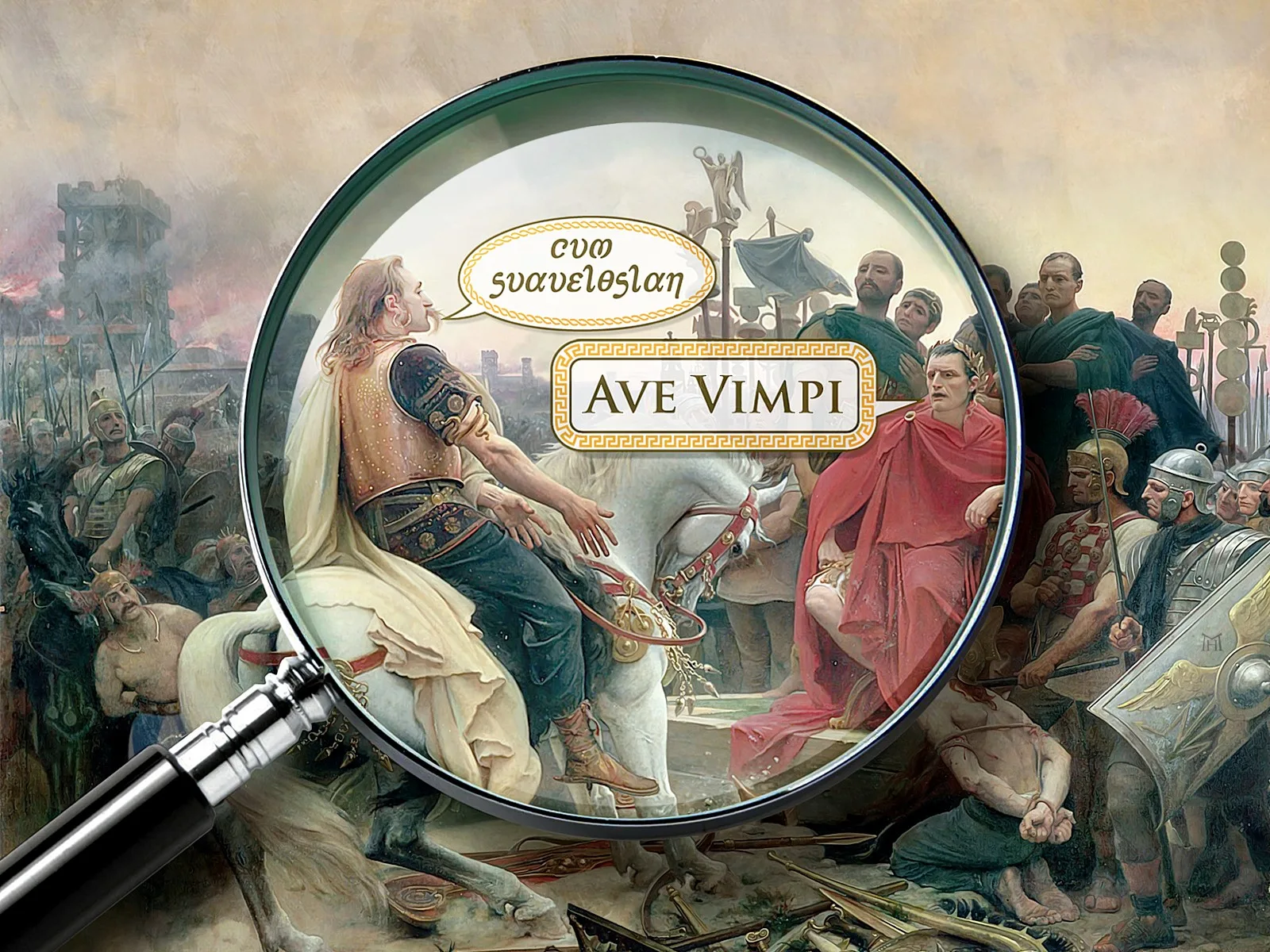

The spindle whorls with the Latin-Gallic inscriptions ‘nata vimpi curmi da’ (Pretty girl, give beer!) and ‘marcosior Maternia’ (I want to ride Materna) were recreated for a touring exhibition by the European Research Council. YouTube / PottedHistory