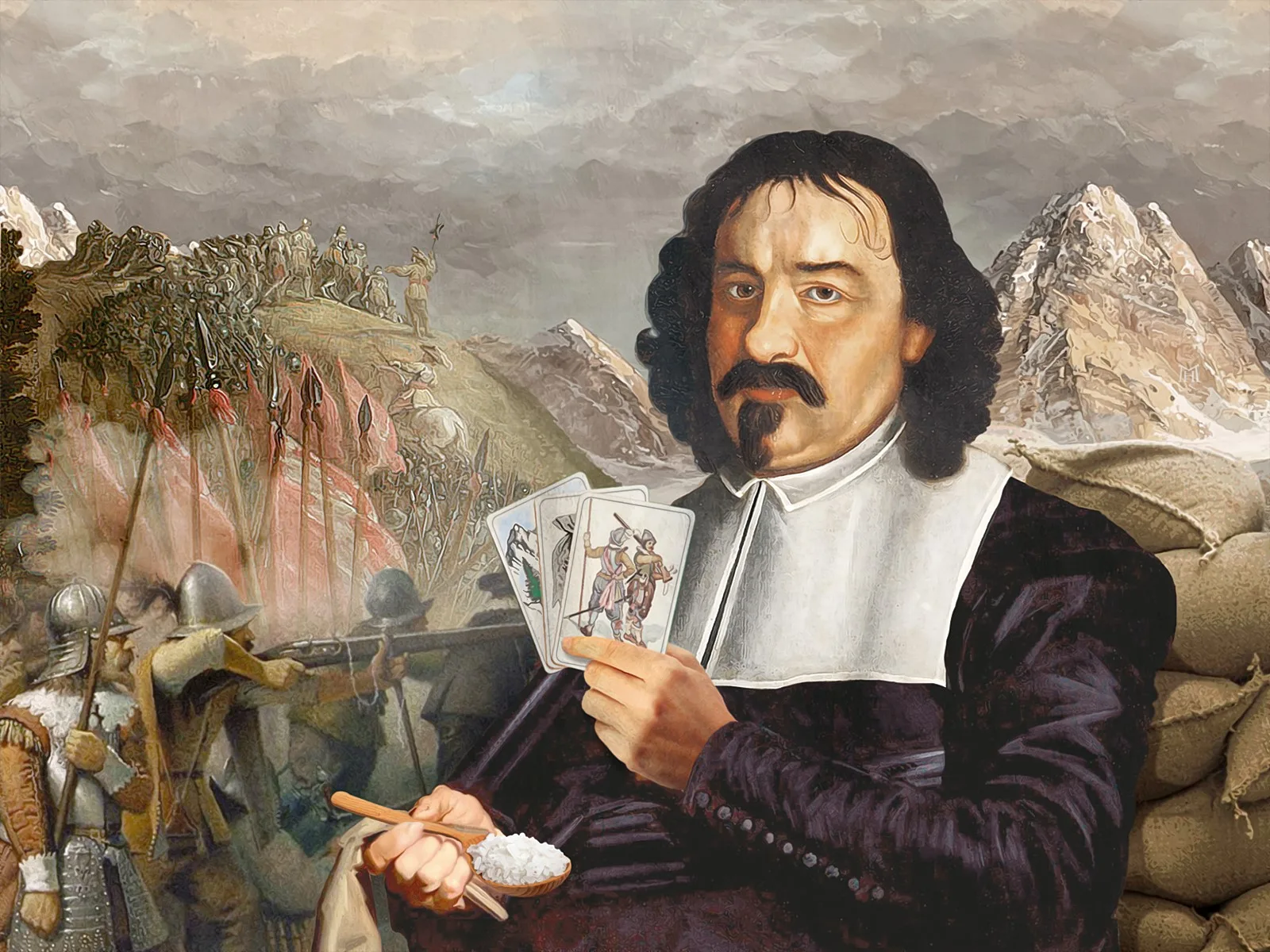

The use of mercenaries by Zurich and Bern against central Switzerland

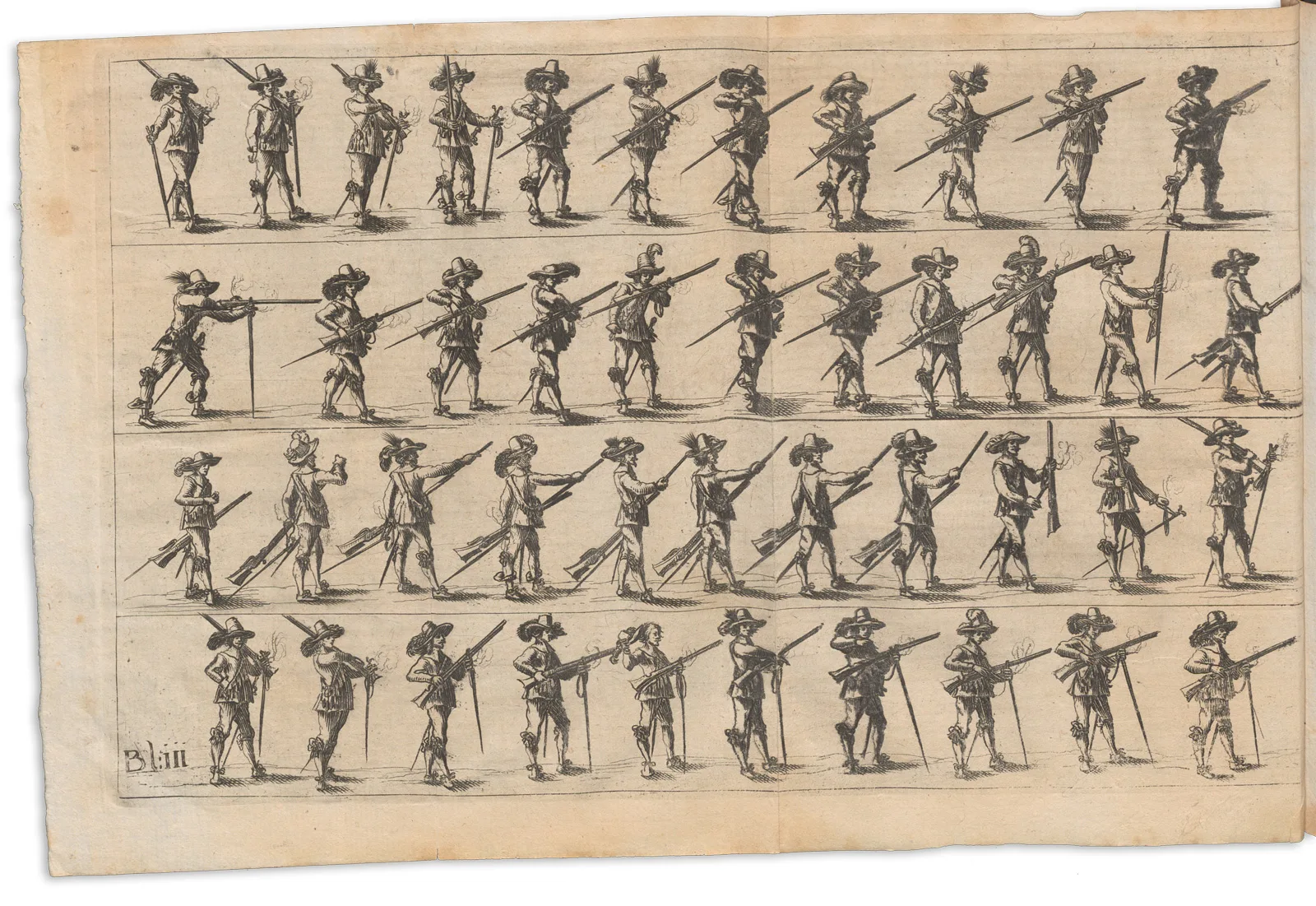

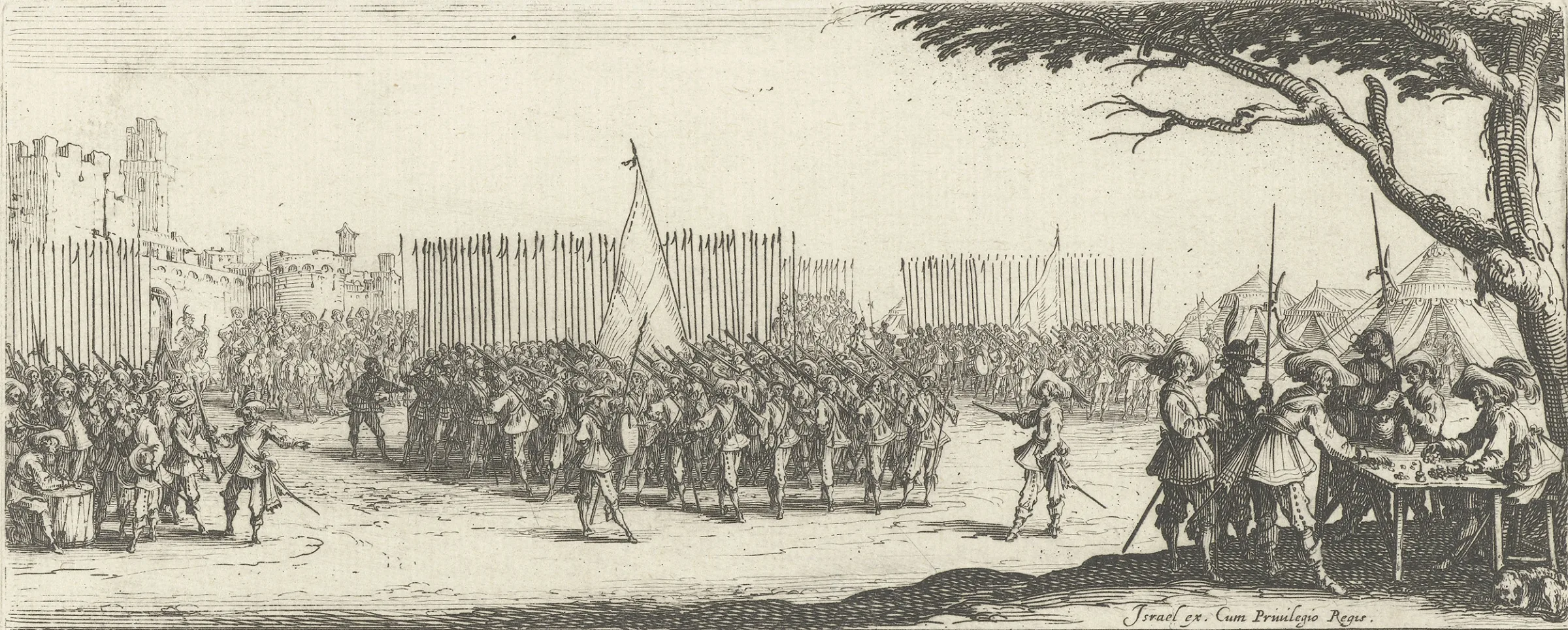

In the 17th century, Zurich and Bern took steps to bring in foreign troops for support in conflicts against their catholic countrymen. Why was their own militia not enough and what did the two cities hope to gain by bringing in mercenaries to fight for them?

And it is hereby deemed necessary that a number of foreign soldiers are hired immediately on foot and horseback on behalf of and paid for jointly pro rata by each canton and at whatever cost is necessary.