A story of resistance and escape

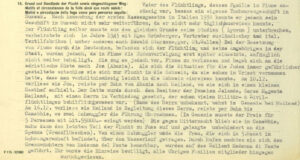

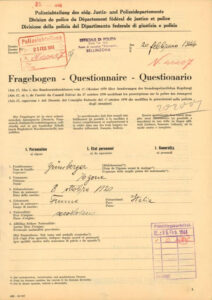

During the Second World War, numerous people attempted to flee persecution across the Italian-Swiss border into Ticino. This included Egone Gruenberger, who only managed to escape to freedom on his second attempt and after a long ordeal.

Portraits of Egone and Edith Gruenberger. Swiss Federal Archives

Rapid change in refugee policy

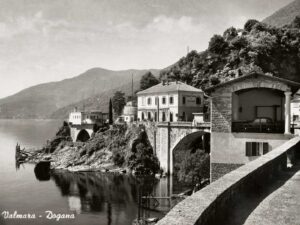

In the region between Ascona and Verbania, there is the Percorso della Speranza, which traces the events of this period, while the Insubrica Historica association offers a trek along the routes taken by refugees, partisans and deserters to reach Switzerland.