The Zurich Art Controversy: Ferdinand Hodler and the Swiss National Museum

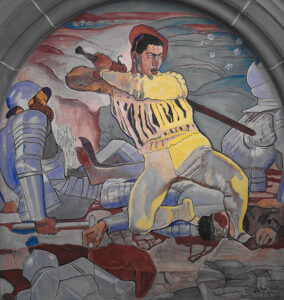

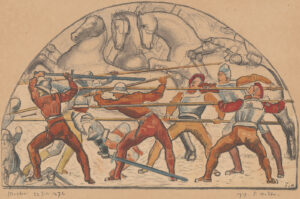

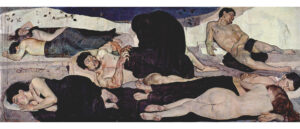

In 1900, the Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler created three frescoes the armory hall of the Swiss National Museum in Zurich. Hodler ignored the wishes of his patrons and sparked a nationwide controversy with the composition of the picture for his work «The Retreat from Marignano».

Colour exists simultaneously with form. Both elements are constantly associated but color strikes you more — a rose for instance — sometimes form — the human body.

A “Quarrel of Frescoes”

My paintings of Marignano represent and characterize the Swiss people by showing their heroism, their force, their perseverance, and the fraternity of our warriors in misfortune.

A Swiss National Treasure