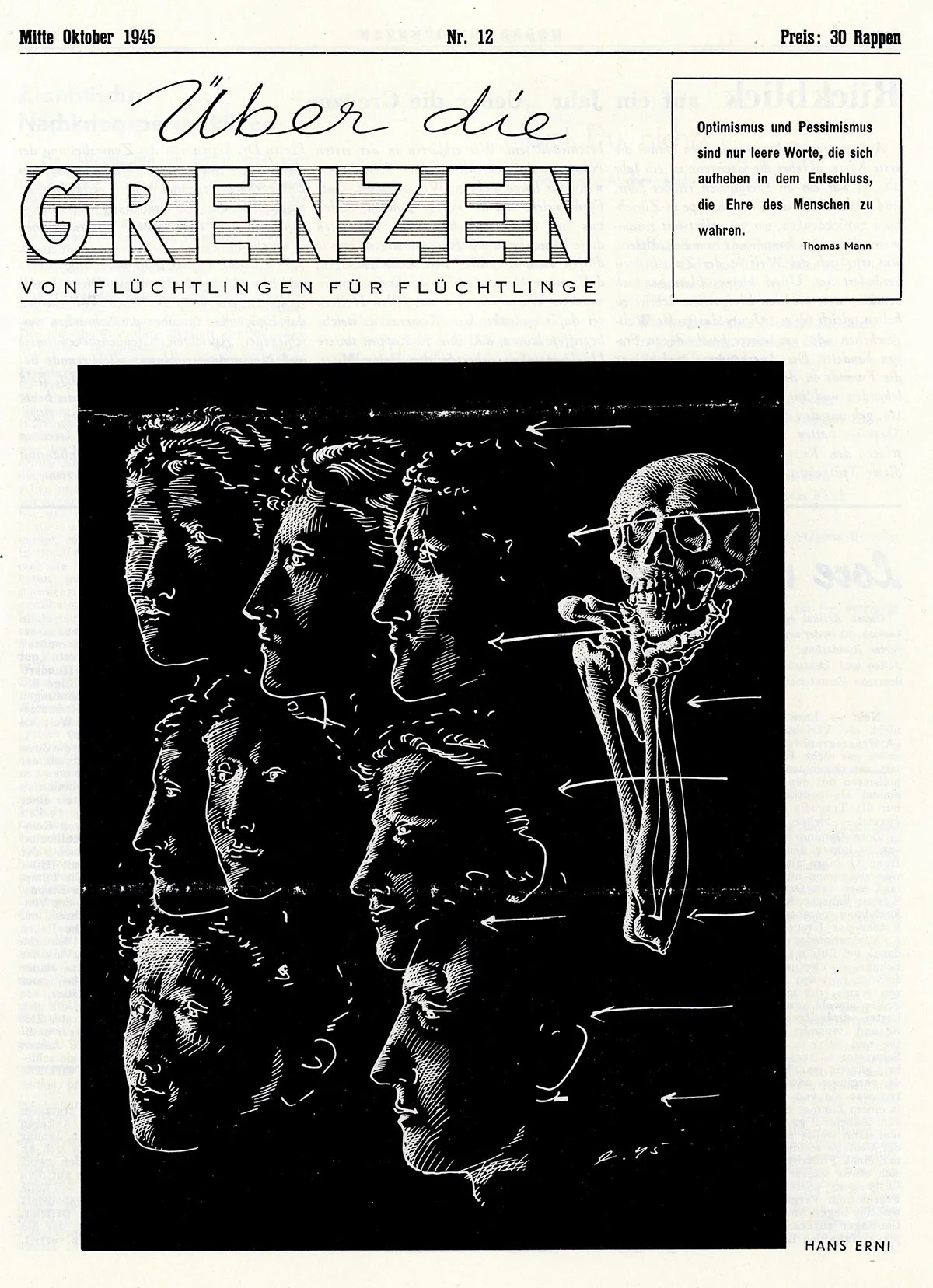

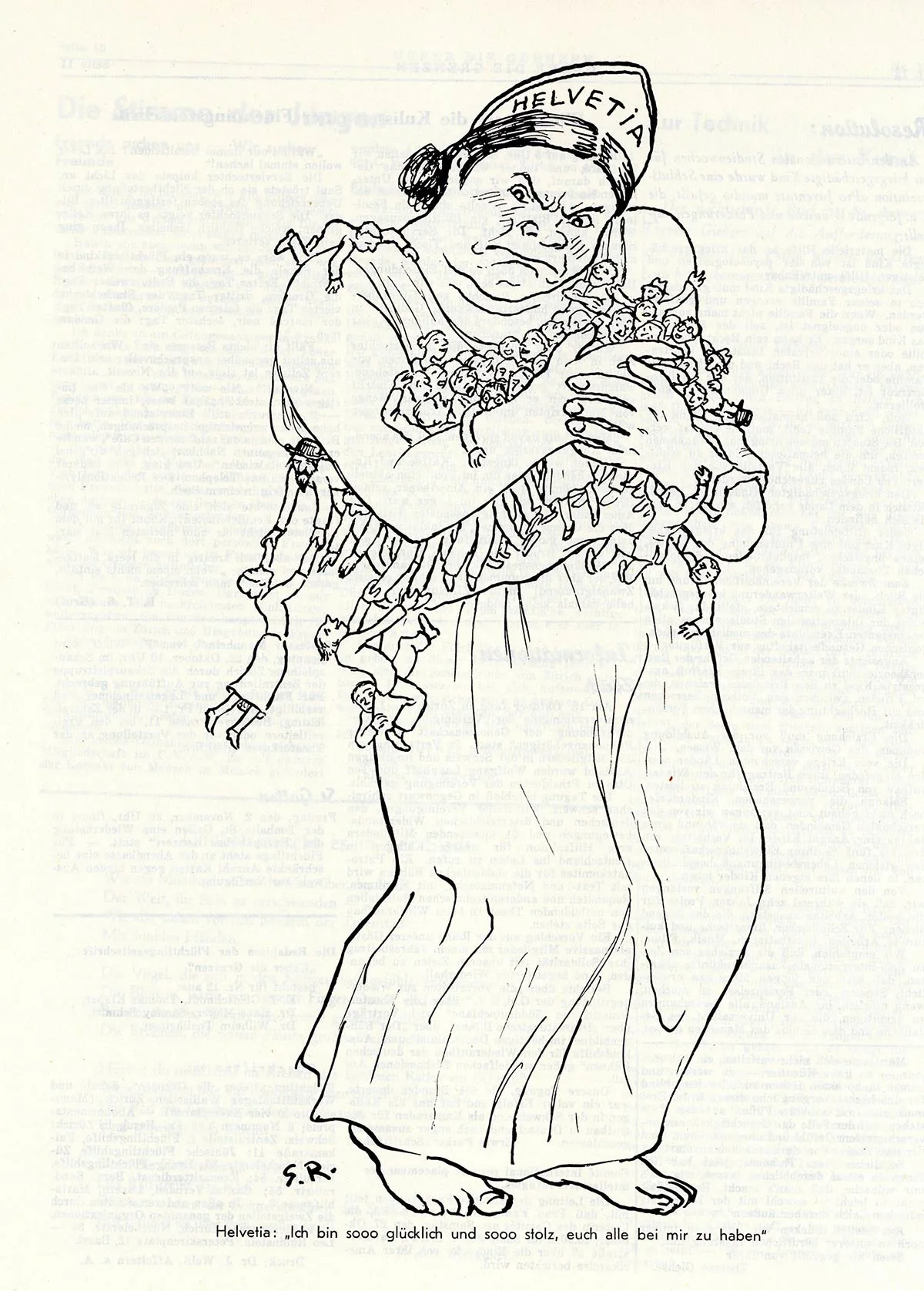

A newspaper by refugees for refugees

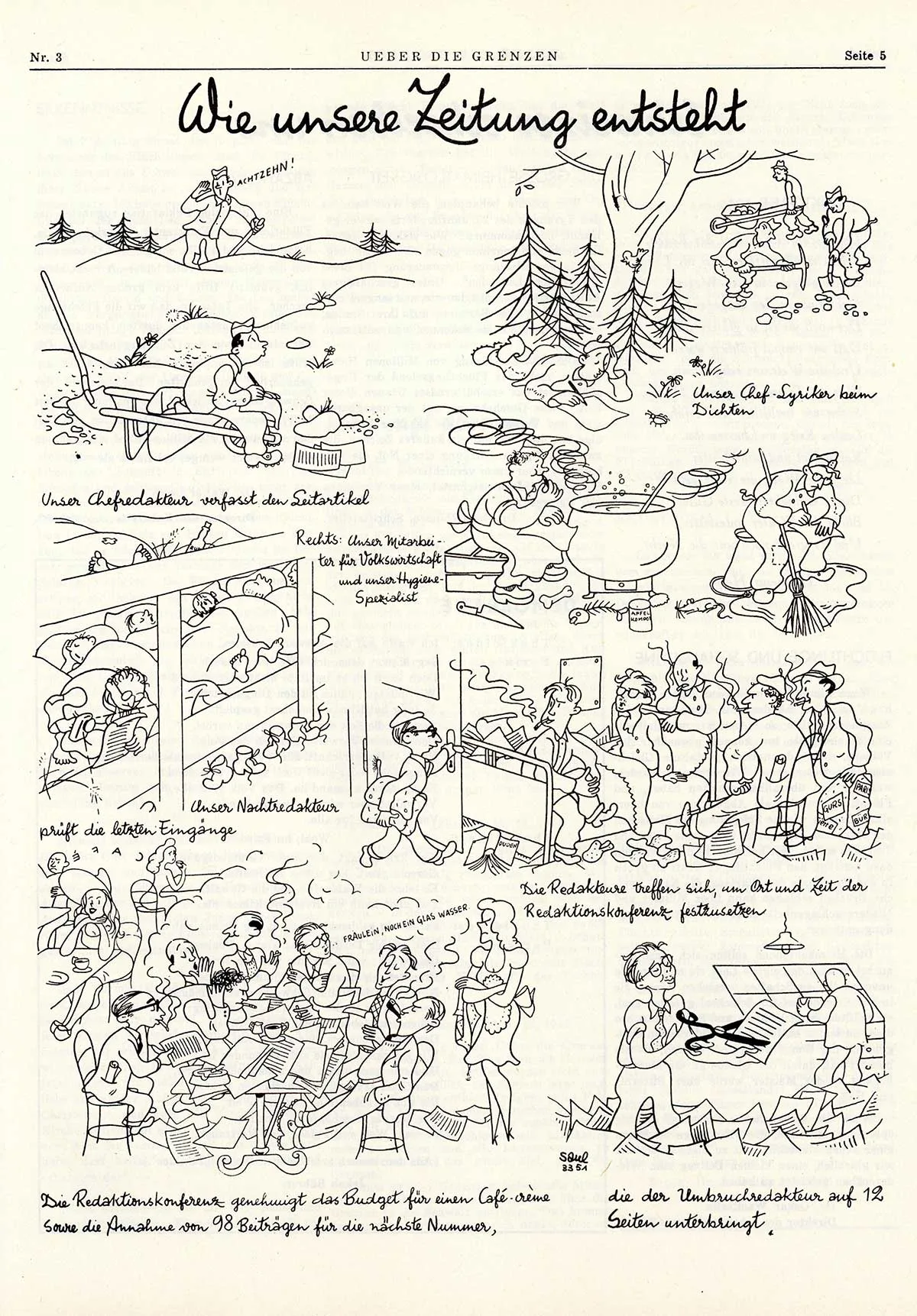

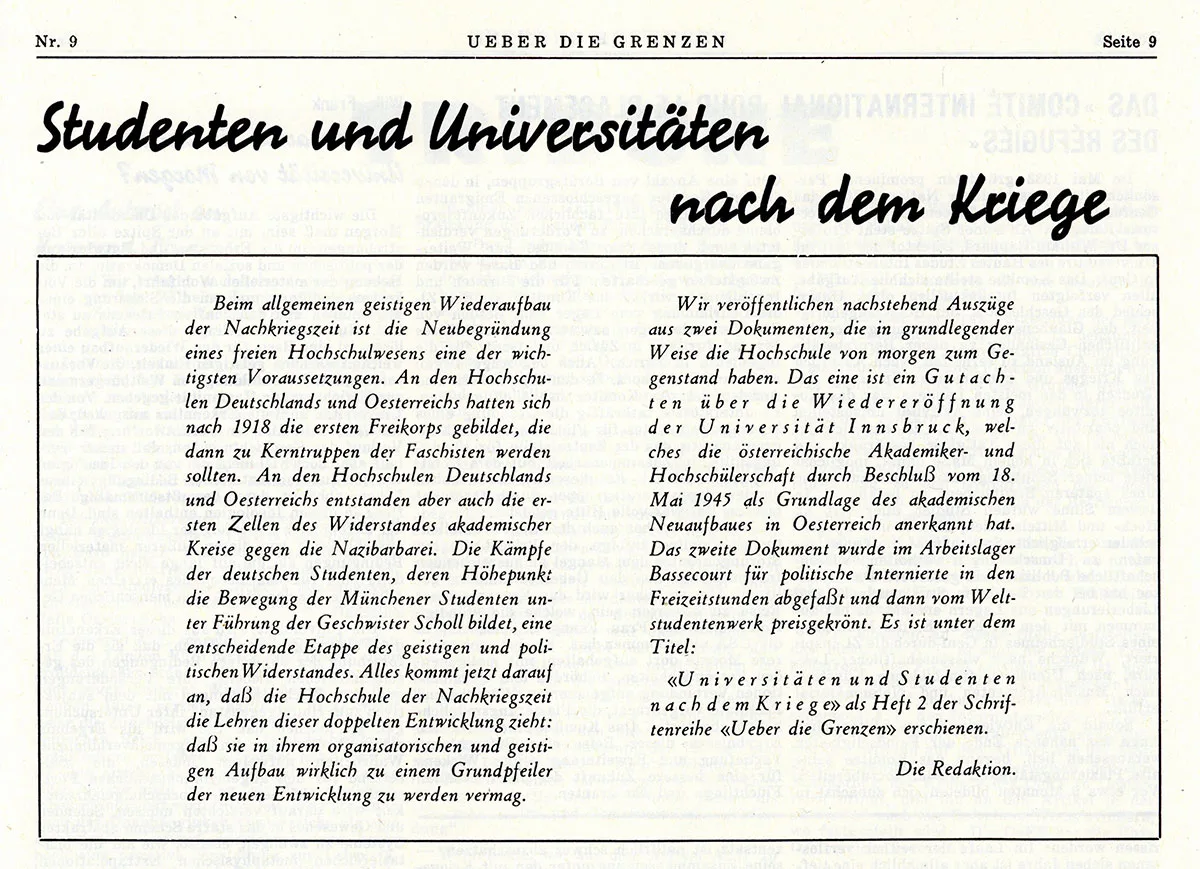

Towards the end of the Second World War, a newspaper was published in Switzerland that was not intended for public distribution yet nevertheless circulated throughout the country. It was written by emigrants in the internment camps.

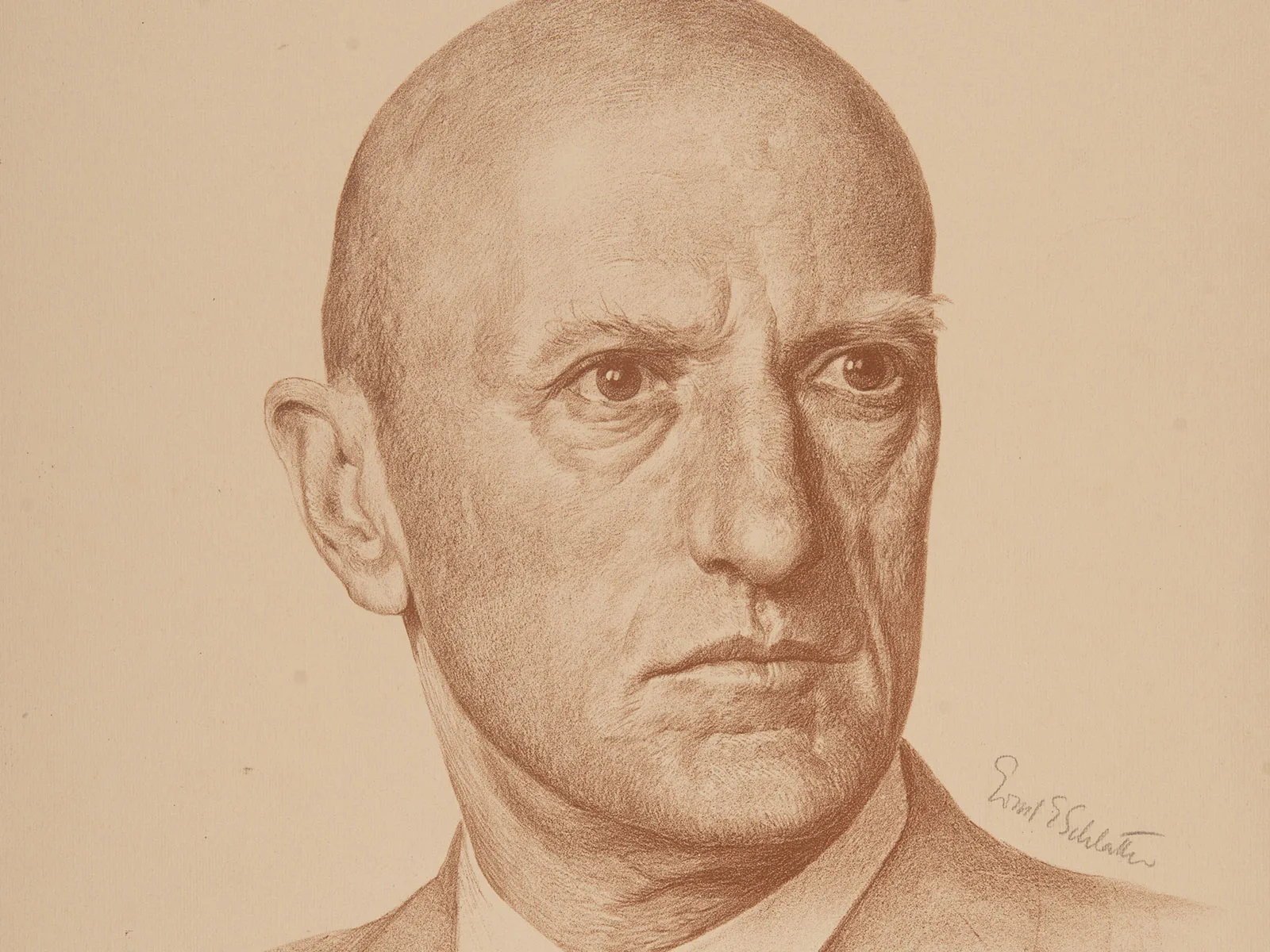

The future cultural elite of the GDR