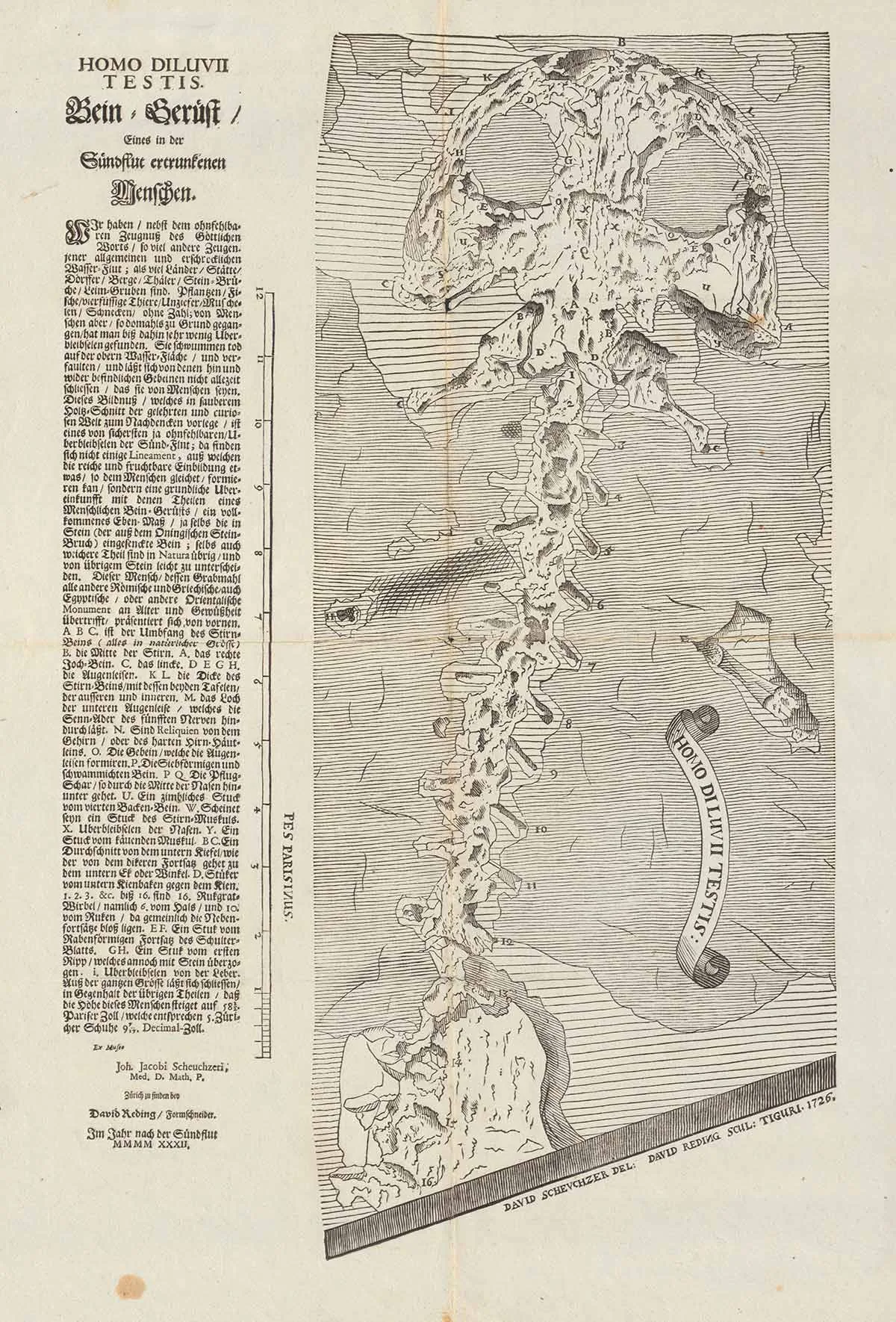

A witness to the Deluge

The fossilised skeleton of a giant salamander found in the stone quarries at Öhningen is one of the most famous fossil finds in history. Zurich-born Johann Jakob Scheuchzer believed it to be the remains of a human who had drowned in the biblical Flood.

A pioneer of palaeontology