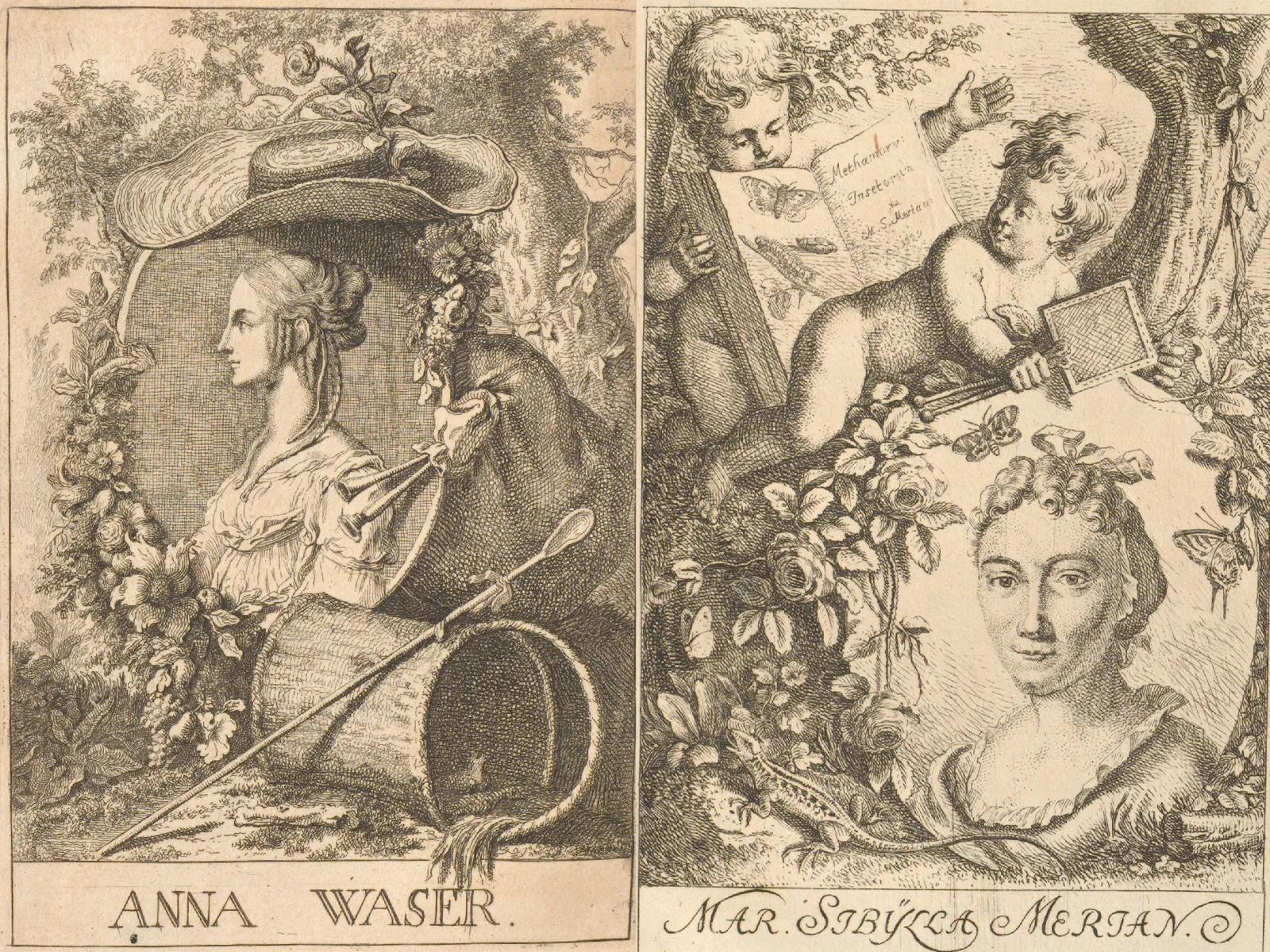

Waser and Merian – two trailblazing female artists of the Baroque era

The Baroque period saw increasing numbers of female artists begin to question the social structures of the age. The stories of Anna Waser and Maria Sibylla Merian demonstrate how these female artists fully bore comparison with their male contemporaries.

Anna Waser – from Werner's pupil to court painter

![The Devil's Bridge is pictured in barren, craggy surroundings. Illustration from Johann Jakob Scheuchzer’s Ouresiphoites Helveticus, sive, itinera per Helvetiae alpinas […], 1723.](https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/app/uploads/teufelsbrucke-waser.webp)

Maria Sibylla Merian – the study of nature and its metamorphoses