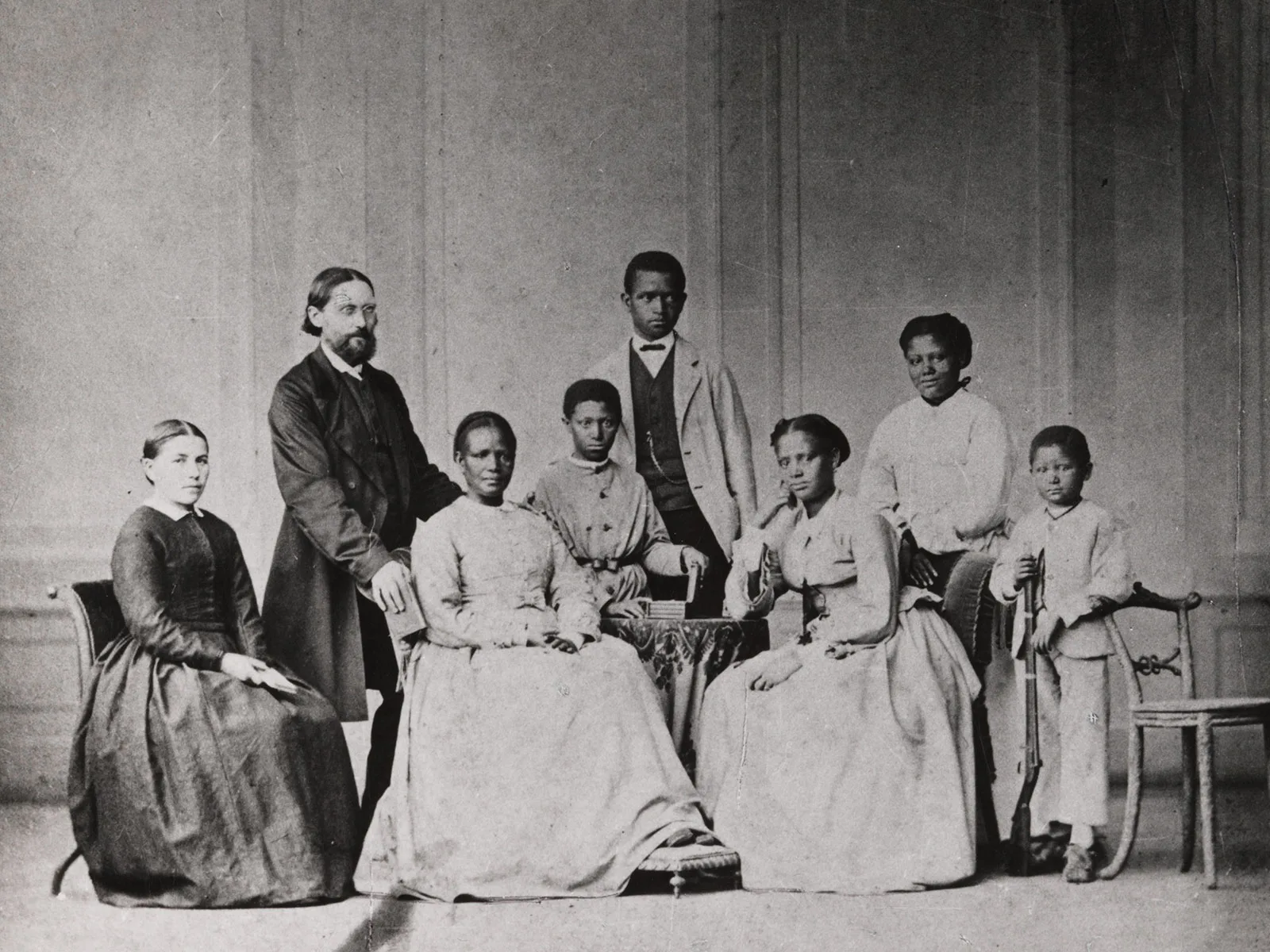

The Basel Mission’s first African female teacher

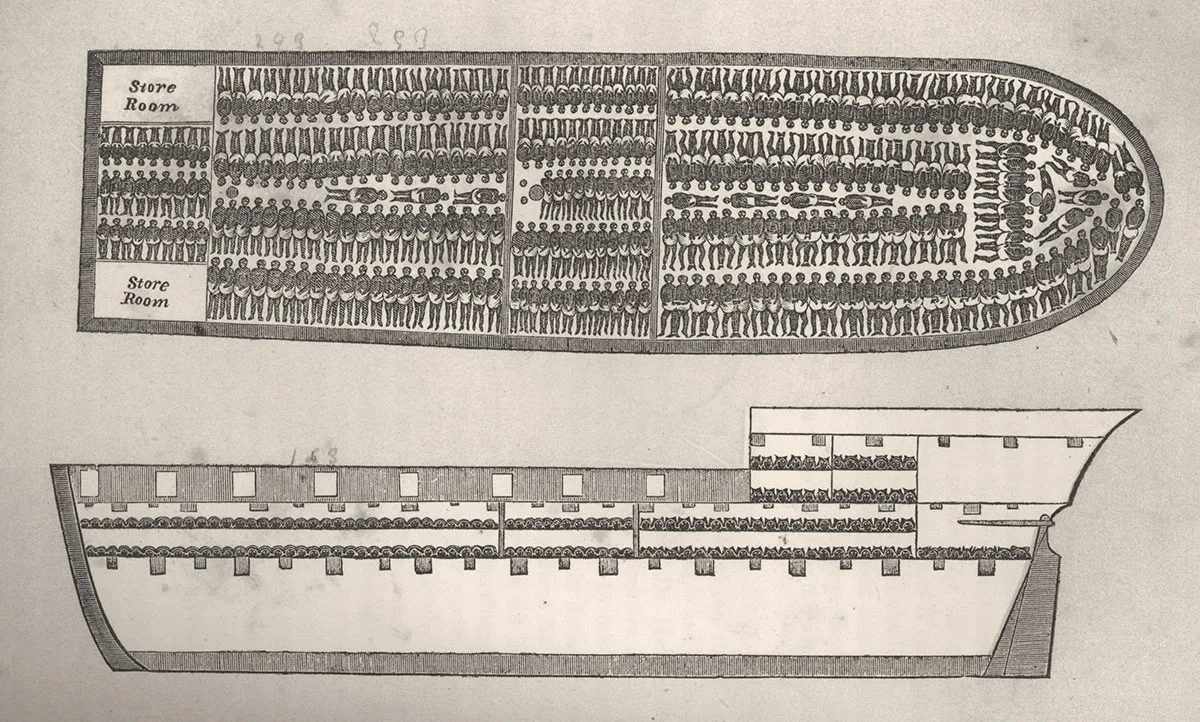

The life of Catherine Zimmermann-Mulgrave tells a story of human trafficking as part of the slave trade and of Christian missionary work in West Africa in the 19th century. It also shows how an African woman managed to lead an independent and self-determined life despite being kidnapped and marginalised.

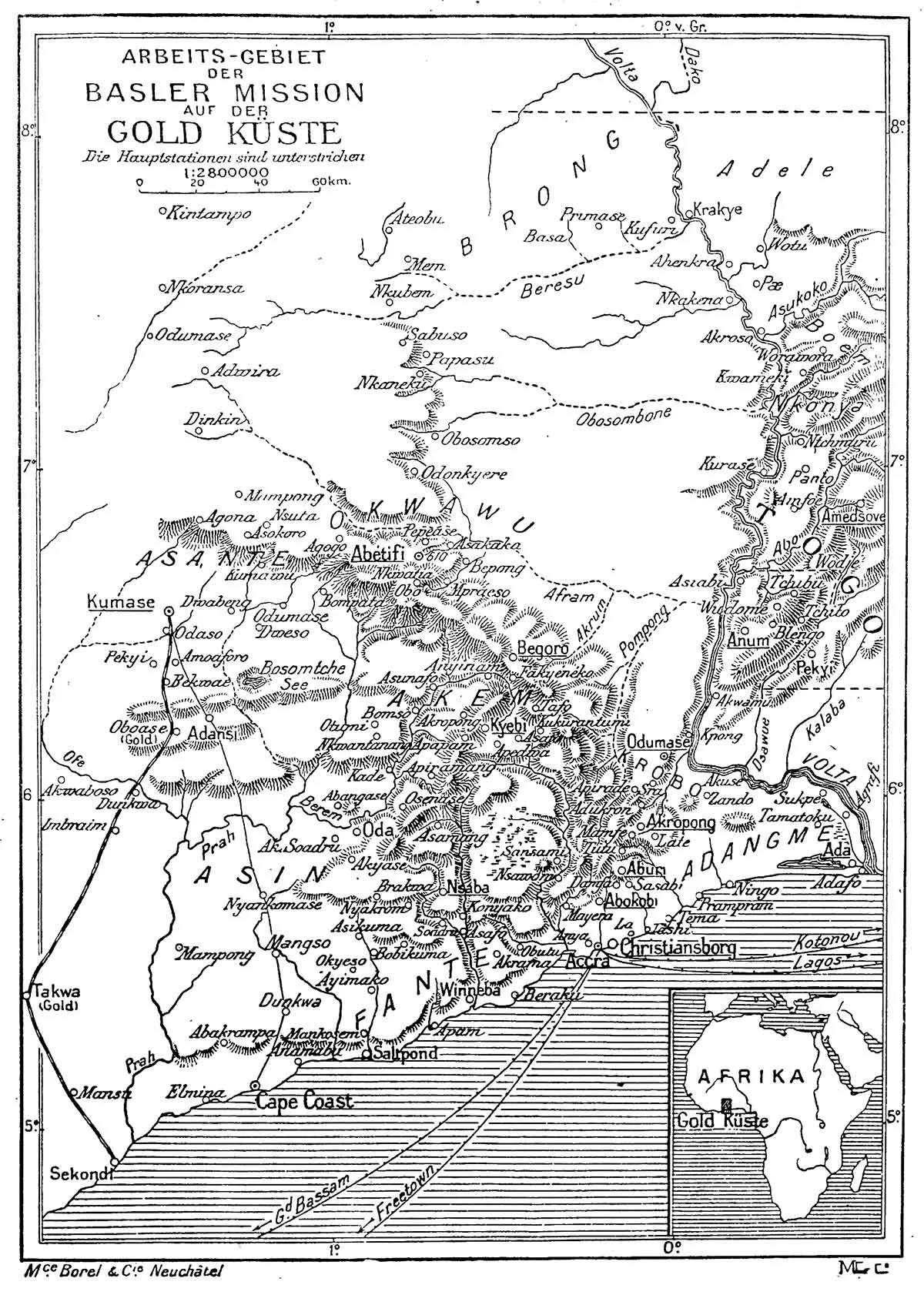

Zimmermann-Mulgrave was only in Europe for a short time. Her adopted home was the Gold Coast, which is now Ghana. She spent decades teaching children (mainly girls) in missionary schools there. Her everyday life was hardly different from that of any other missionary woman. At the same time it was extraordinary: a mother of seven, she also had a job; a black person, she was also a teacher and missionary; a divorcee, she was still accepted and respected.

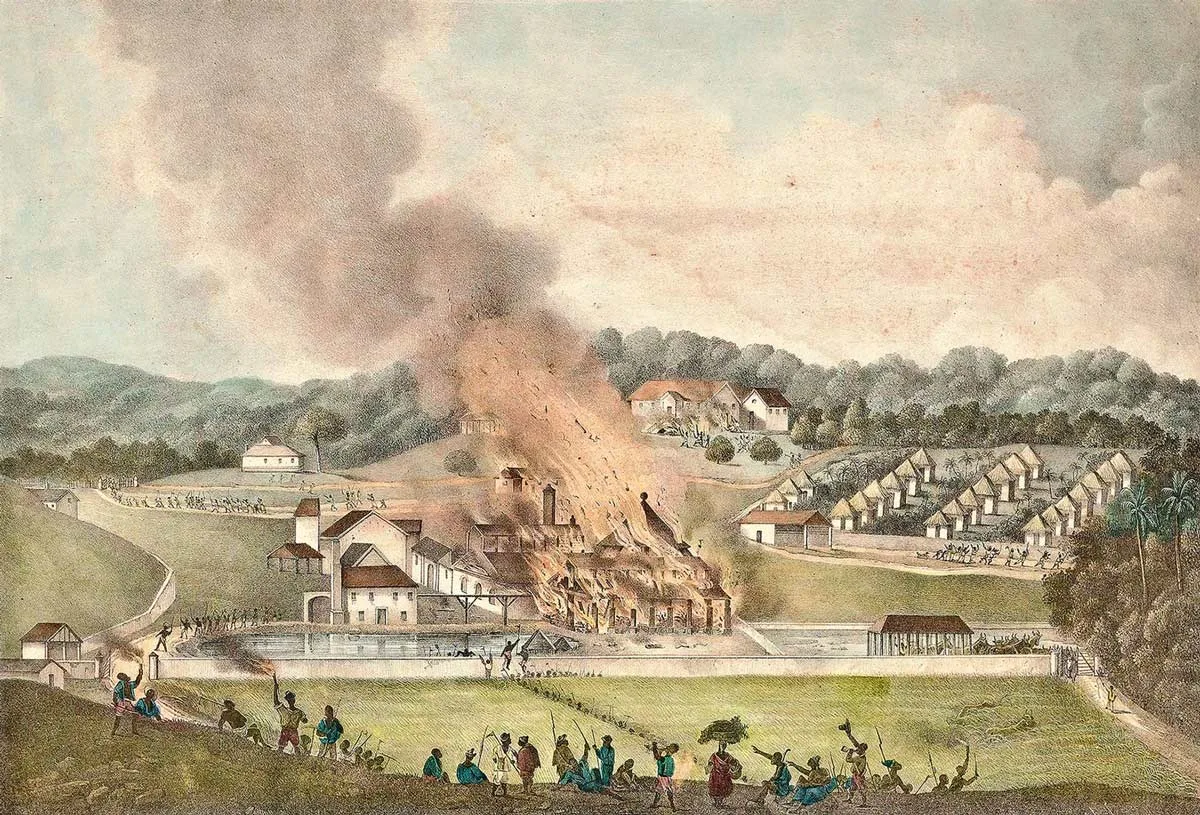

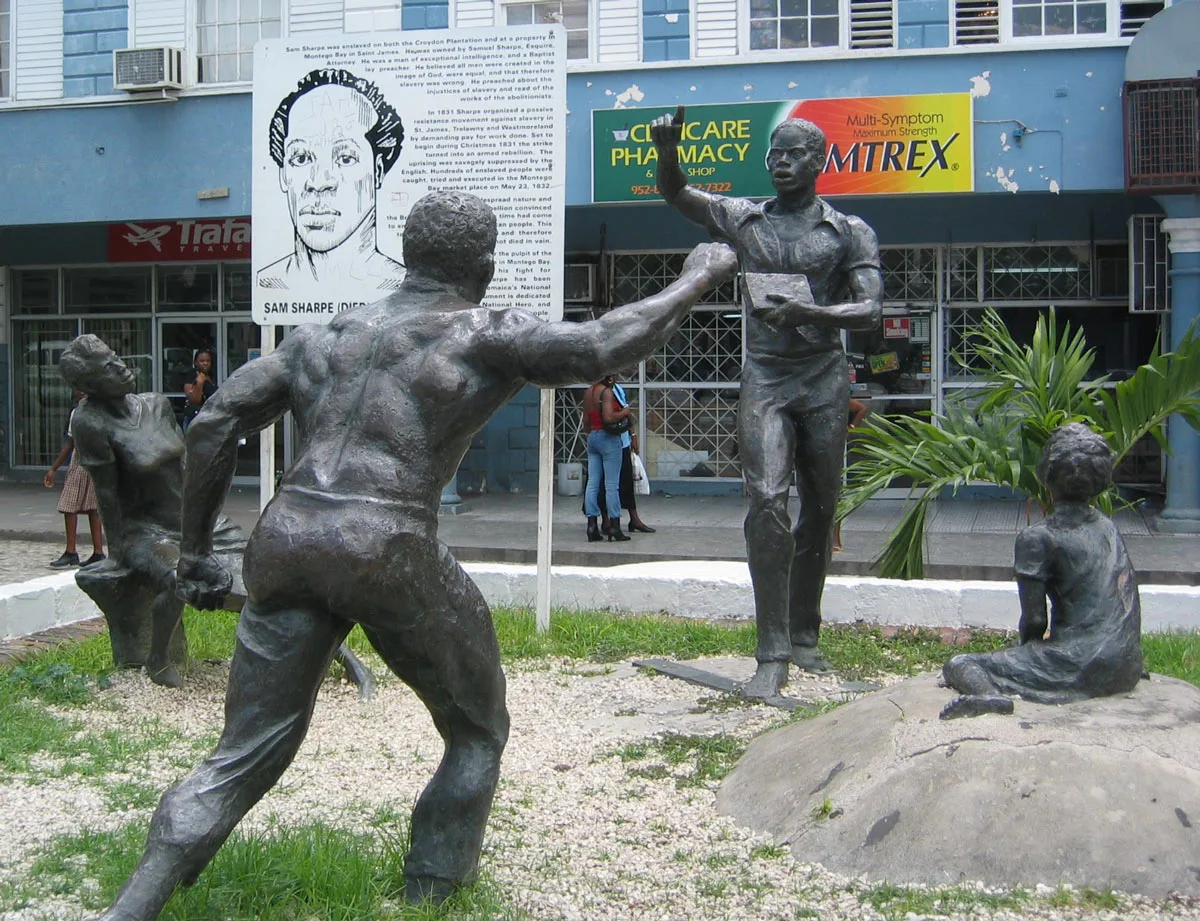

The bible says no to slavery

Jamaica was still marked by the suppression of the biggest slave uprising in its history, known as the Baptist War. Around the turn of the year 1831/32, enslaved men and women, led by slave and lay preacher Samuel Sharpe, had risen up against the plantation owners.

Divorced and a single parent

George Thompson had many affairs, allegedly even with schoolgirls. Catherine had just turned 20 when she was “legally” divorced at her own request. She was granted custody of their children and took back her old name of Mulgrave. The Basel Mission gave her their blessing to marry again. She was able to keep working as a teacher, and her ex-husband left the Mission. The Basel Mission took a hard line with George Thompson, who had become increasingly dependent on alcohol. His behaviour was explicitly at odds with Christian ethics, which the missionaries considered the only “civilised” way to behave.

Thompson had to be let go from the Mission after a short time due to serious cases of misconduct. He fell deeper into sin and his sinful ways caused a judicial divorce from his God-fearing wife for reasons according to which by the teachings of Christ (Matth. 5 vs 32) divorce is also justified in the eyes of God.

Support from his fellow missionaries allowed Zimmermann to stay with the Mission, although he was reprimanded: he was deemed to have “gone against proper civil standards” and was henceforth to be “considered as definitively stationed in Africa”. His annual leave in his homeland of Germany was cancelled. The German hardly considered this punishment, as he called the Gold Coast his “second home”. He learned Ga, translated the Bible and compiled dictionaries and a grammar guide in the local language.

The husband passes away in Europe

When they had been married for 20 years, Catherine and her husband, who was now struggling to cope with the West African climate, went to Europe with some of their children. On his second visit to his hometown of Gerlingen in south Germany, where they had travelled via Basel, Johannes Zimmermann died of a tropical disease at the end of 1876, aged just 51. The widowed Catherine returned to her chosen home of Accra on the Gold Coast. She lived there until 1891 as the “oldest member of the Basel mission family”. After her death, the Basel Mission said she was “loved by Christians and heathens alike”.