From Borneo to Bern

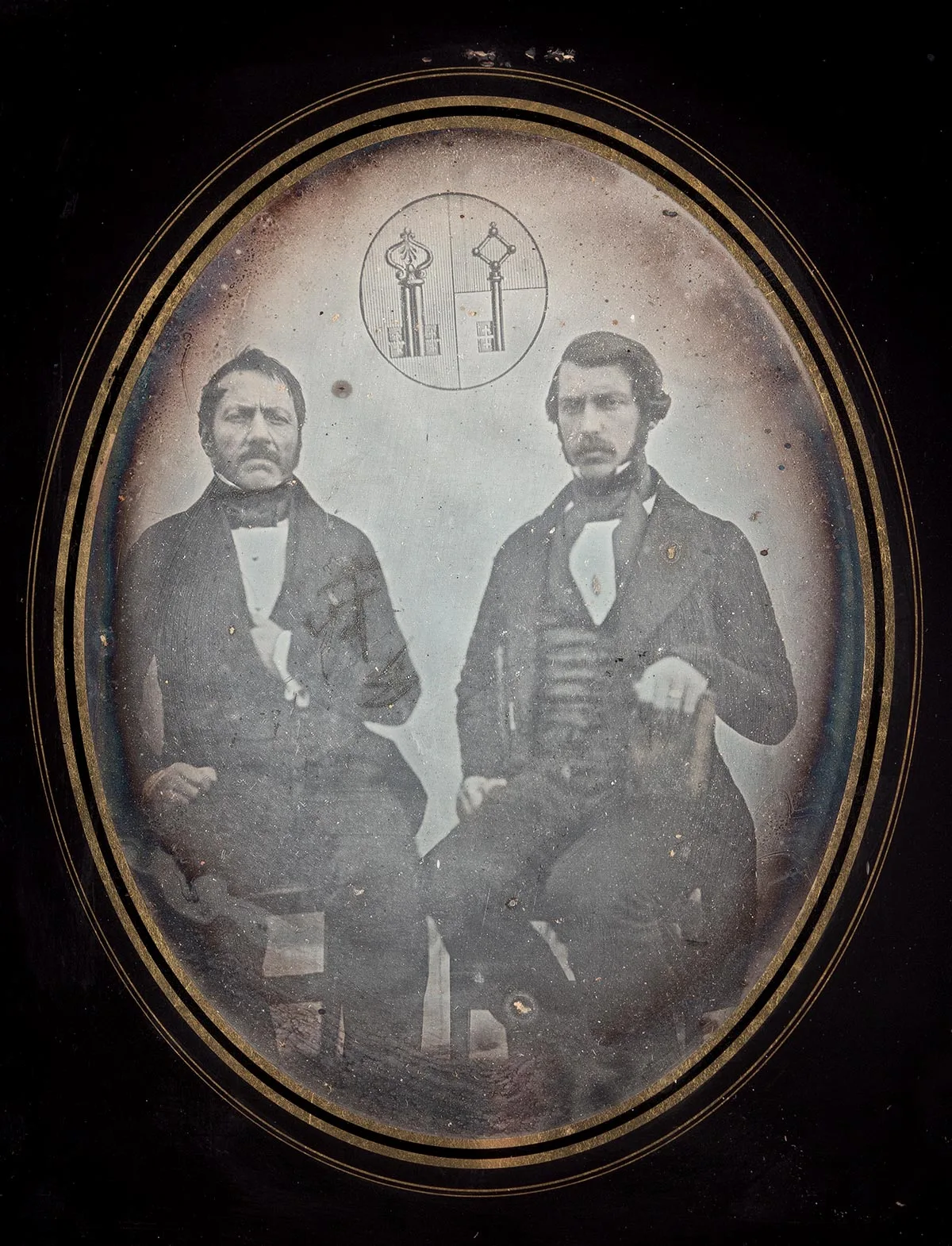

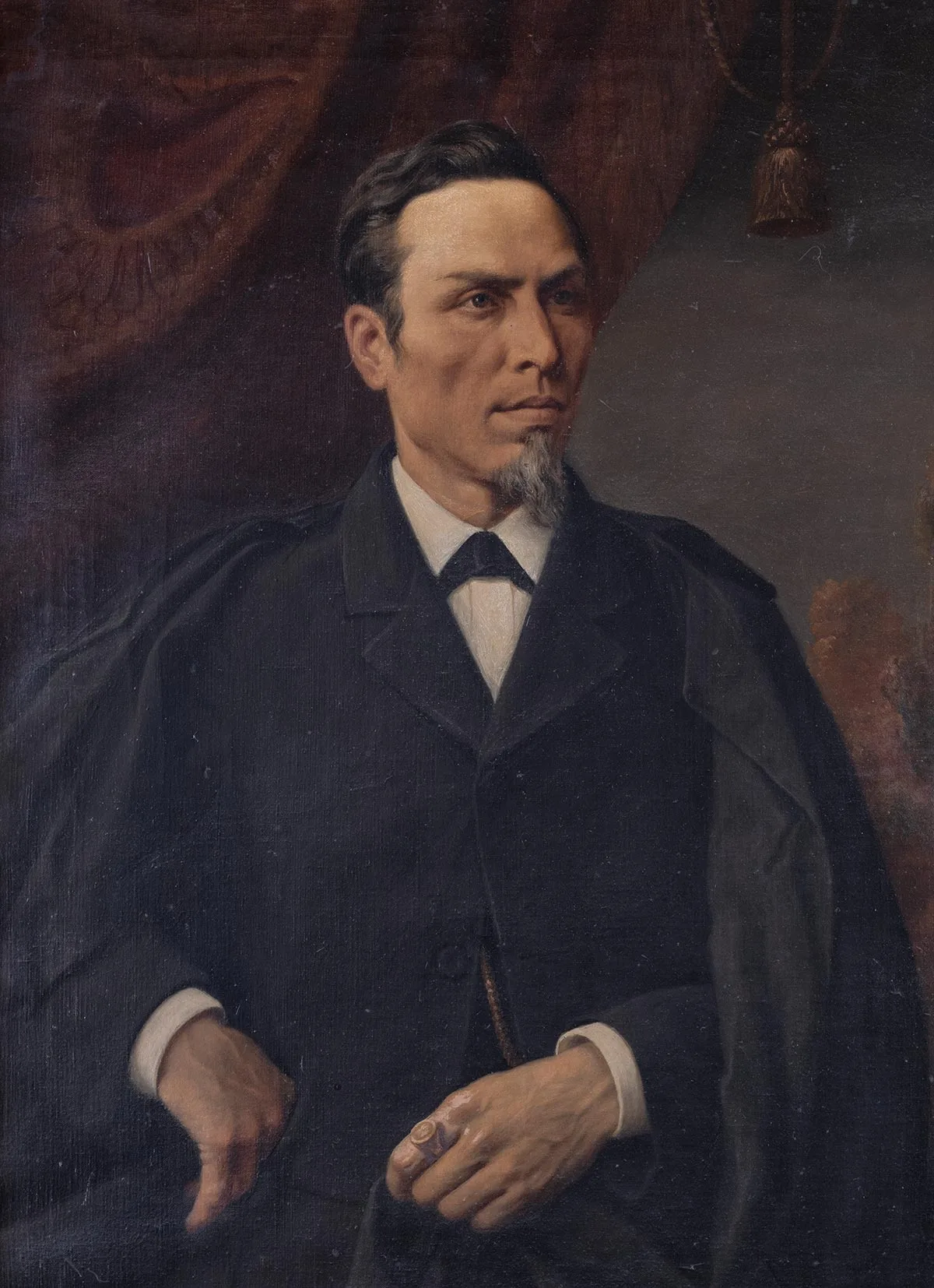

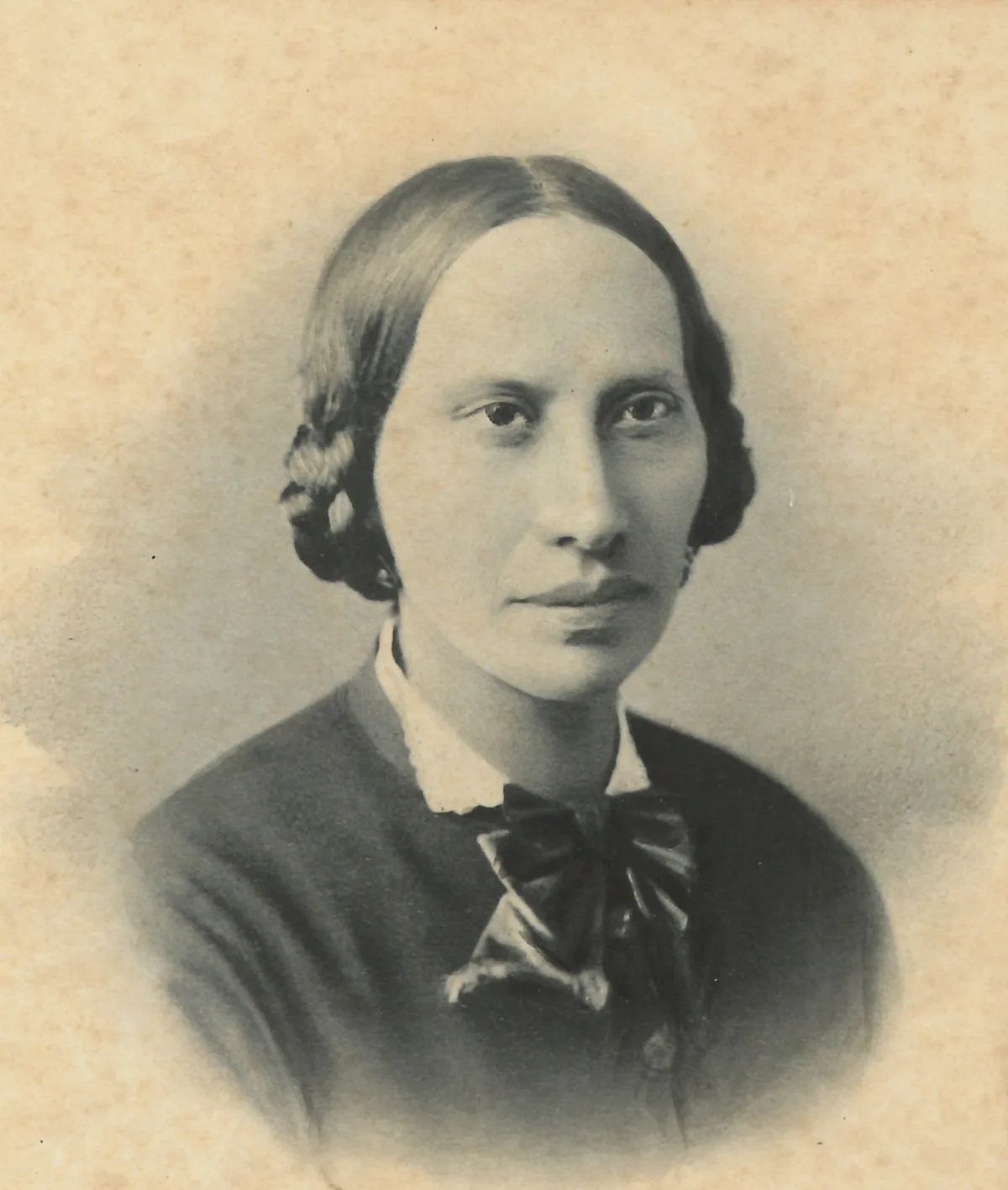

In 1860, Alois Wyrsch from Stans was the first non-white member of parliament. A Nidwalden citizen “of colour”? Wyrsch’s mother came from Borneo, where his father had served as a mercenary soldier.

Mother tongue banned

Supporter of the revised Federal Constitution