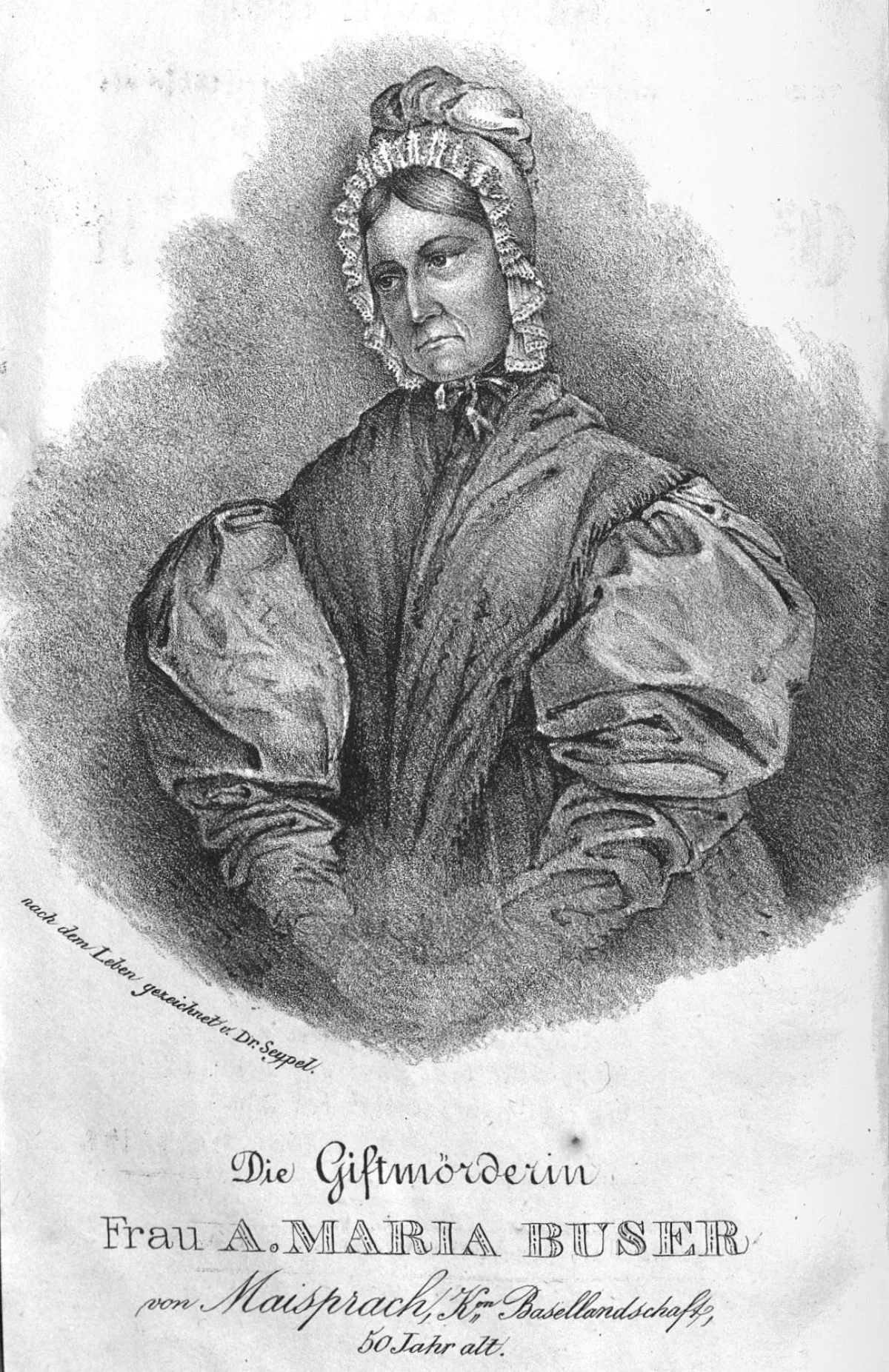

A poisoned marriage: the Buser case

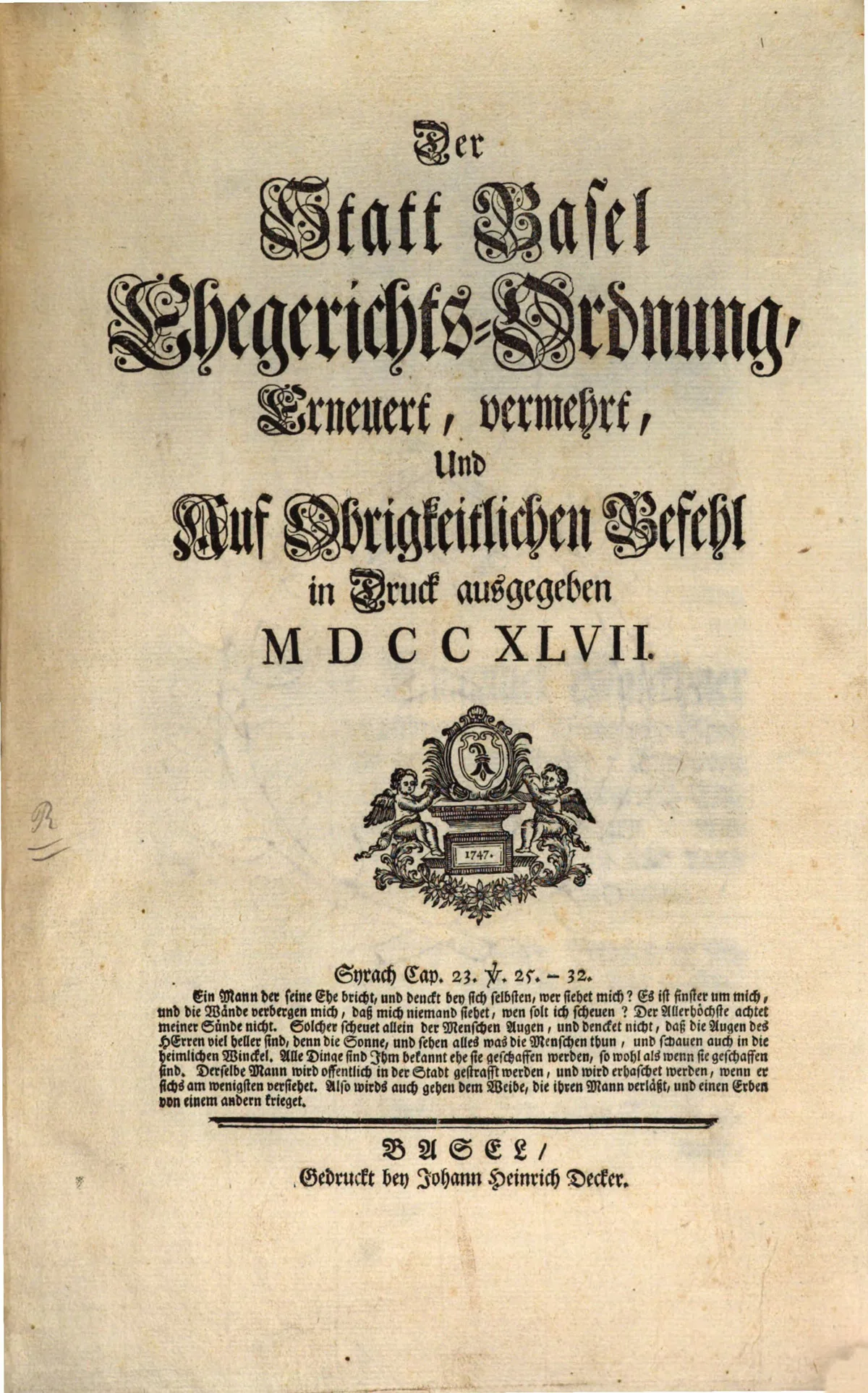

The restrictive divorce laws of the 19th century repeatedly led to human tragedies. In the case of the Buser couple, they even resulted in murder.

Feeling forsaken by God, a meanness gradually developed in her heart, and with time that meanness turned into a loathing towards her spouse, who, through his drunkenness, diminished their earthly possessions and undermined their supposed happiness.

Suspicions confirmed

The sulphuric acid had been in the house for ten years, while the hydrochloric acid had been procured the previous winter from a Dr Gaß in Muttenz to treat a sick horse. Anna poured the lead oxide into Heinrich’s grape brandy which had been coloured with black cherries. “He didn’t notice a thing,” she remarked in the hearing.

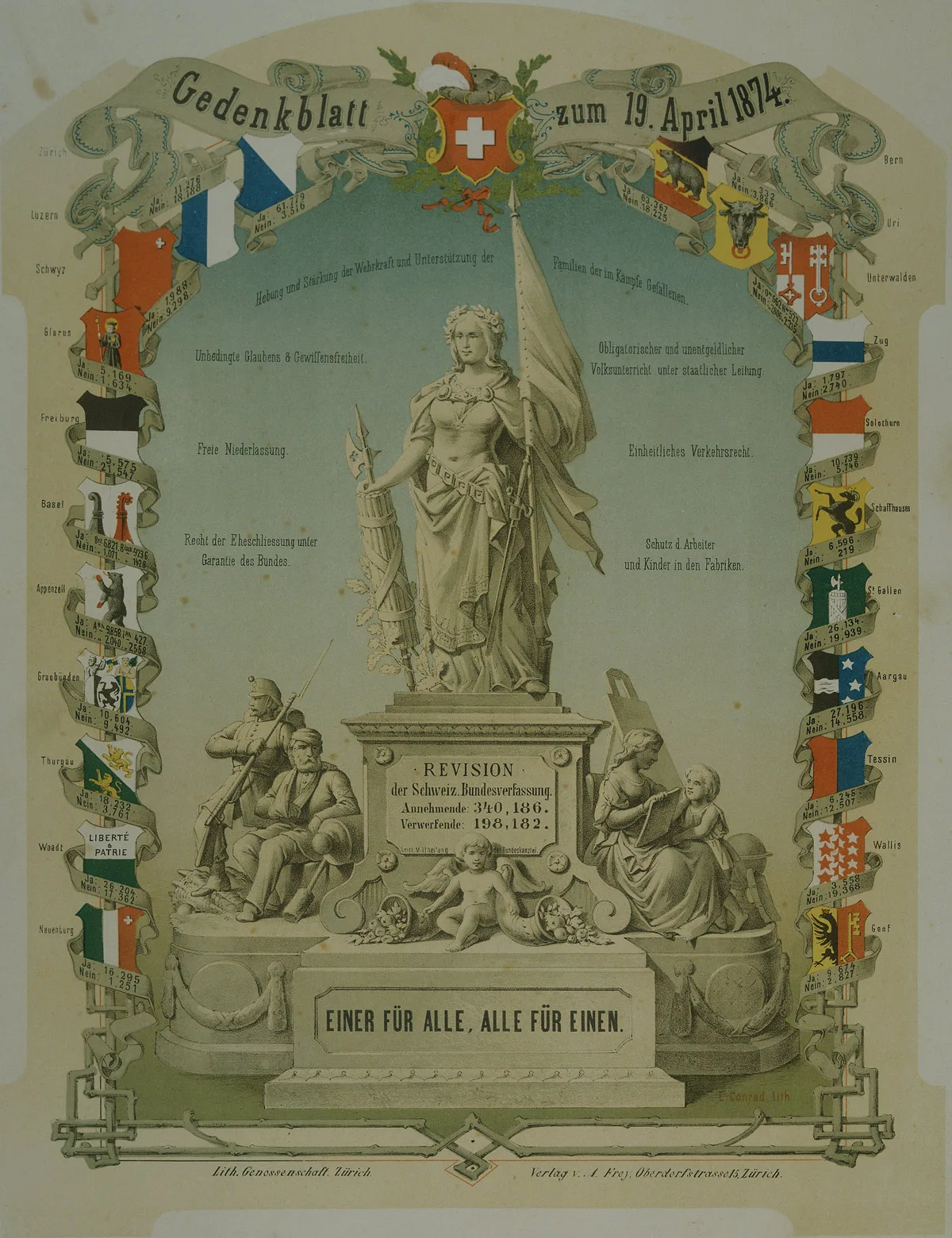

A change ahead of its time

A clear verdict