Lies, torture, death: the case of Anna Koch

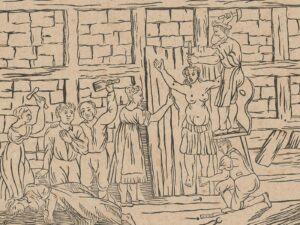

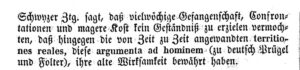

In 1849, Johann Mazenauer was suspected of murdering his girlfriend. The authorities in Appenzell wanted a confession and would use any means to get one. But they failed, as the woman was actually killed by the accused’s ex-lover.

No compensation for Mazenauer