Resistance helpers from Ticino

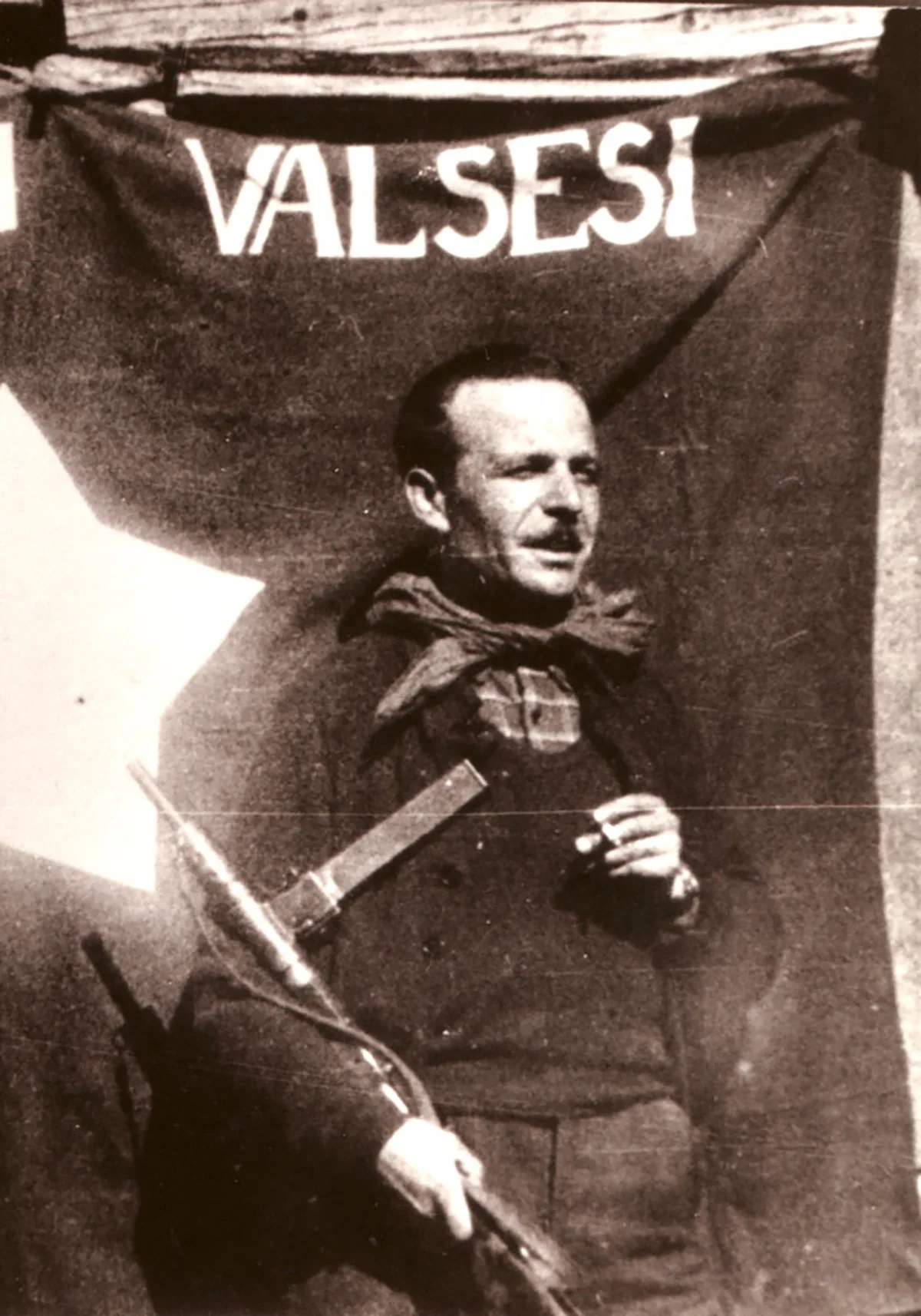

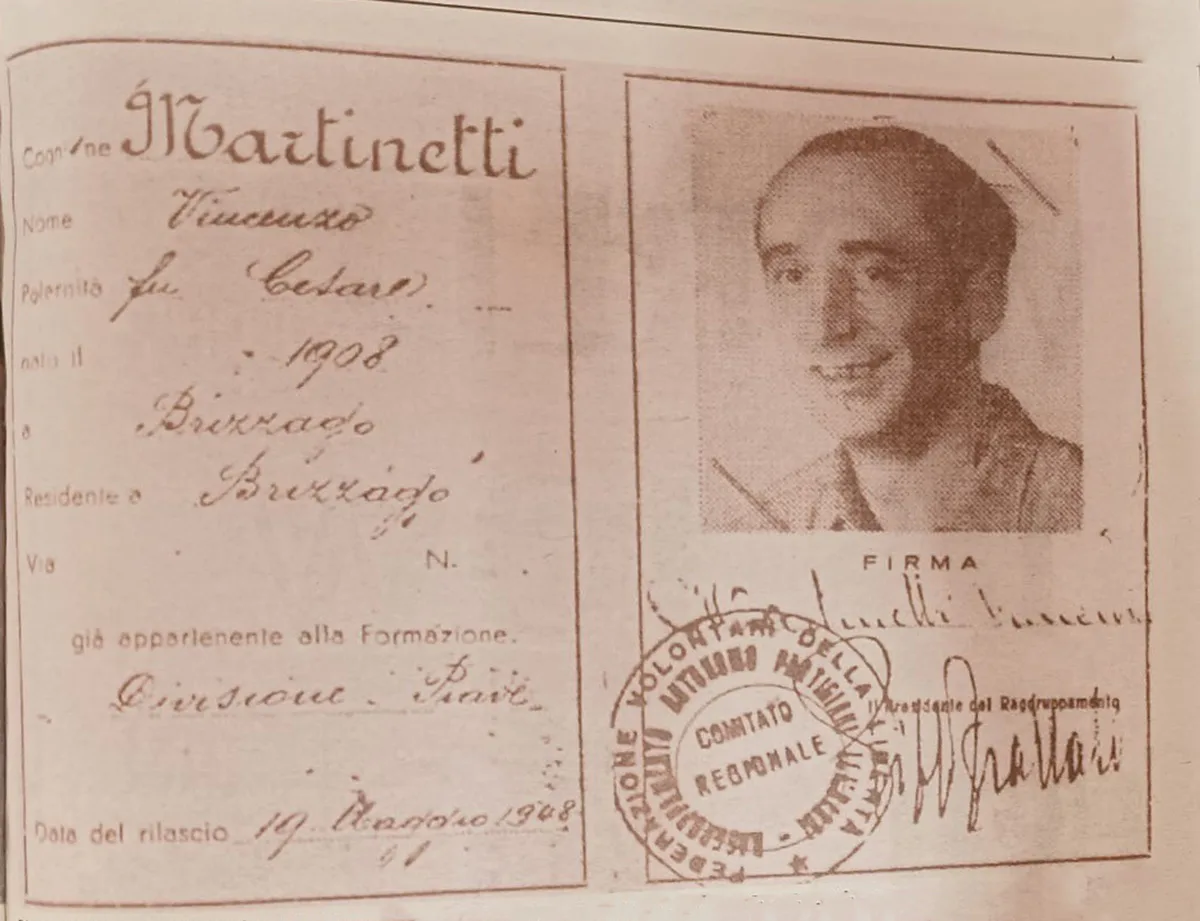

For two years up to 1945, partisans in Italy's Domodossola area fought against the German Wehrmacht and its allies. Some Swiss also joined the struggle: as helpers and resistance fighters.

Lots of small groups

Lack of equipment

Communists versus anti-communists