Wikimedia / SBB Historic

Showdown at the Simplon

On 22 April 1945 Italian partisans, together with the Swiss secret service, foiled a plot to blow up the Simplon Tunnel. The German Wehrmacht had planned to destroy it.

On 19 March 1945, Adolf Hitler ordered a scorched earth tactic. The advancing Allies were to encounter infrastructure that was as far as possible unusable. This included the southern portal of the Simplon Tunnel, near the Italian village of Varzo. The portal was to be dynamited, along with power stations and factories in the Ossola region. Preparations for this had already begun in November 1944.

A special unit consisting of around 30 Wehrmacht soldiers from Eisenbahn-Pionier-Bau-Batallion 12 (a railway pioneer construction battalion) was in charge of the project. After the re-occupation of the Ossola region (see box), the men had already rebuilt the destroyed bridges and viaducts. Most of these soldiers came from Austria, and knew their job well. However, like most members of the Wehrmacht, they were demoralised and poorly equipped. The scant material they had – compressors, pumps and various tools – was repeatedly sabotaged by SBB employees stationed in Domodossola and Varzo. In four months, all they had succeeded in doing was lay three small powder holes at the tunnel entrance. Since the partisans had returned to the area around the Simplon in January 1945 there had been sporadic skirmishes, which made the work even more difficult.

Some of the explosives that were destroyed in April 1945 were stored in this railway cottage in Varzo.

insubricahistorica.ch

SWISS SECRET SERVICE RIGHT IN THE THICK OF IT

The Germans’ plans had not gone unnoticed by the Swiss intelligence service, which had built up a tight-knit spy network in the region. In addition to staff of the Federal Railways, shopkeepers, hoteliers and postal workers also acted as informants. The most prominent representative of the secret service was 30-year-old Peter Bammatter. Officially Bammatter, a Valais native, was assistant director of the Swiss customs office in Domodossola. However, that was just a cover. Bammatter was in fact the captain of the secret service, and in this role he was the real Swiss information hub for the region.

When the Wehrmacht began its preparations for blowing up the tunnel, Bammatter and the intelligence service reacted immediately and investigated the situation. Since the German soldiers, and their equipment, pulled back to Varzo in the evenings, the Swiss were able to get an accurate picture of the situation by night. Thanks in particular to Paul Bardet, an SBB engineer and army captain from Sitten, they knew exactly what was going on. Bardet ventured into the tunnel several times from the Brig end and provided very detailed reports after each of these exploratory forays.

The situation was serious, but not hopeless. A total of around 400 tonnes of obsolete naval projectiles, still containing explosives, had been transported to Varzo and from there to the tunnel. However, since the Wehrmacht soldiers lacked the necessary tools and knowledge to carry out precise drilling, the Swiss intelligence service judged the risk of complete destruction to be quite small. But the detonation still needed to be prevented. So in March, Peter Bammatter contacted the Italian resistance fighters.

Naval projectiles at Varzo railway station. Some weighed up to 150 kilograms.

insubricahistorica.ch

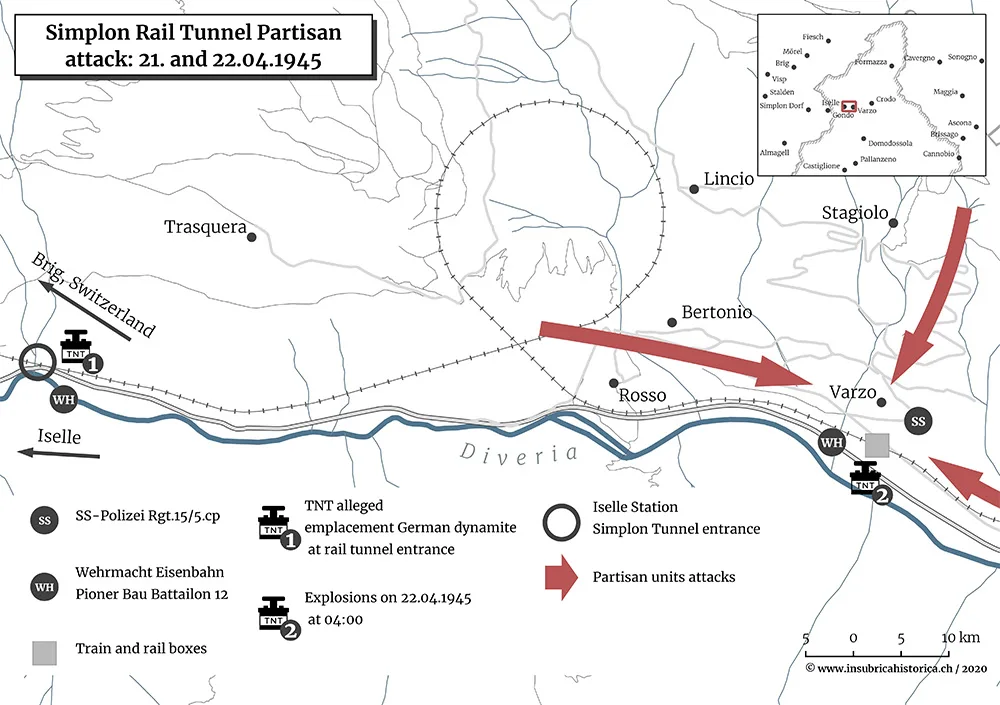

Map of the partisan attack in Varzo on 22 April 1945.

insubricahistorica.ch

INFO FOR THE PARTISANS, WINE FOR THE GERMANS

While the partisans were supplied with information about the Germans’ destructive plans, Bammatter also went to work on the Wehrmacht soldiers. The war was lost and many of them were demoralised. This made it possible to have informal talks with some of these men. The Swiss secret service agent also had a number of attractive ‘arguments’ in his luggage, which made his efforts at persuasion easier. The intelligence agency bought cigarettes, wine and food on the black market in Domodossola. These gifts were passed on to the Germans. At the same time, Peter Bammatter tried to convince the soldiers of the futility of blowing up the tunnel.

In the early hours of 22 April 1945, the partisans finally attacked. Their objective was to destroy all the explosives. Because a group of the resistance fighters blockaded the road to the Wehrmacht and SS police garrison in Varzo and the Swiss secret service had persuaded the sentries to defect, the action ended without injuries or fatalities. At 4.30 a.m. the partisans set fire to the explosives that were still lying around in the open at Varzo. The fire was huge, and was visible from a long way off.

The danger of the Simplon Tunnel being blown up was finally averted. However, the action had caused damage to the rail infrastructure. This damage was repaired by a German railway pioneer construction battalion. The soldiers then fled to Switzerland and were interned.

The Ossola Republic

In autumn 1944, Italian resistance fighters liberated a large swathe of the Ossola region and founded a partisan republic. The democratic experiment ended after 44 days, when German combat units recaptured the terrain. Those who could fled to Switzerland. A number of blog articles describe southern Switzerland’s experiences during World War II:

SBB employee Mario Rodoni (left), close colleague of Peter Bammatter, with a German soldier in Varzo.

Casa della Resistenza, Fondotoce / Verbania