Reinforcing the language border – literally

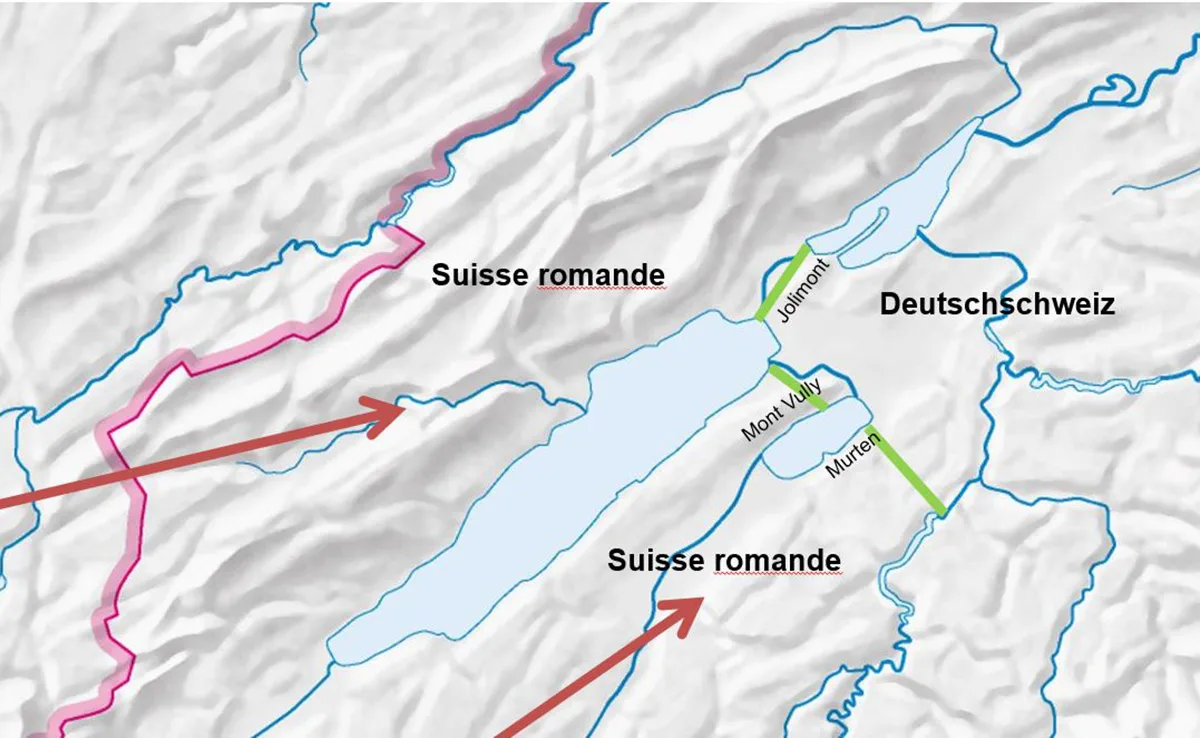

The Murten fortifications were set up in the First World War to defend Switzerland against an attack from the west by France. Trenches and bunkers were dug in the Bernese Seeland and the area around Murten. Many of these structures actually mark the border between the French and German-speaking parts of the country.

Following the outbreak of war in 1914, the Swiss military feared an envelopment attack by France in order to reach Germany’s unfortified southern border. That would have allowed France to circumvent the Western front, which had been deadlocked since autumn 1914. To prepare for such an eventuality, the military command ordered the construction of the Murten fortifications in 1914 to guard the Zihl canal–Mont Vully–Murten–Laupen line and protect Bern from attacks launched from the west of the country.

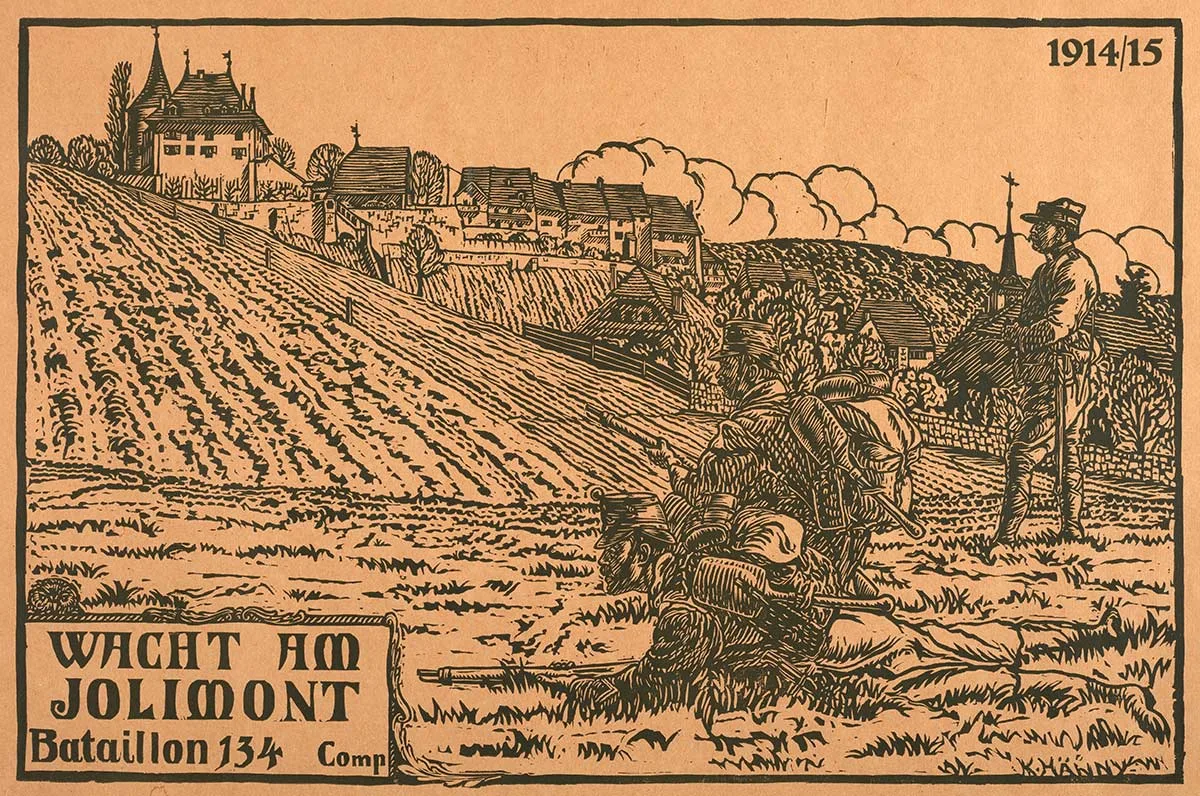

Another fortification was built in the Hauenstein area to protect Olten railway junction and serve as the basis for an offensive defence of the Jura. In addition to the national border in the Jura, the defences of two key military geographic areas to the north of the Alps had thus been strengthened. In September 1914, about 16,000 men were posted to the Murten fortifications. After that, the number of soldiers sent there was greatly reduced. From October 1914 to the end of 1917, the fortifications were manned by 2,000 soldiers on average. About two-thirds of all Swiss troops served at least one spell in a fortified area.

Fortification along the language divide

First and second-class sleeping quarters

The daily drudgery of life in the fortifications mainly took three forms: drill and training, guard duty or working on the fortifications. The soldiers referred to the third activity as “den Tschingg machen”, a reference to the Italian construction workers who, among other things, helped build Switzerland’s railway infrastructure before the war by engaging in mining work.

The Murten fortifications were mainly manned by soldiers over 30 years of age from the ‘Landwehr’ (a reserve unit). Colonel Bolli said in the Council of States that the ‘Landwehr’ were “the best soldiering material we have”. This shows how officers saw their men at the time. Their leadership style was based on the German military model, with distinct hierarchies leading to widespread frustration in the ranks. Operations usually placed situational priorities over people. Military personnel served in the military for 500 days on average and earned a modest wage. There was no such thing as compensation for loss of earnings in those days. This meant many soldiers and their families were at high risk of falling into poverty, and the poor economic and supply conditions only exacerbated the situation. The war ended in Switzerland with the national general strike in 1918.