The queen of watercolours

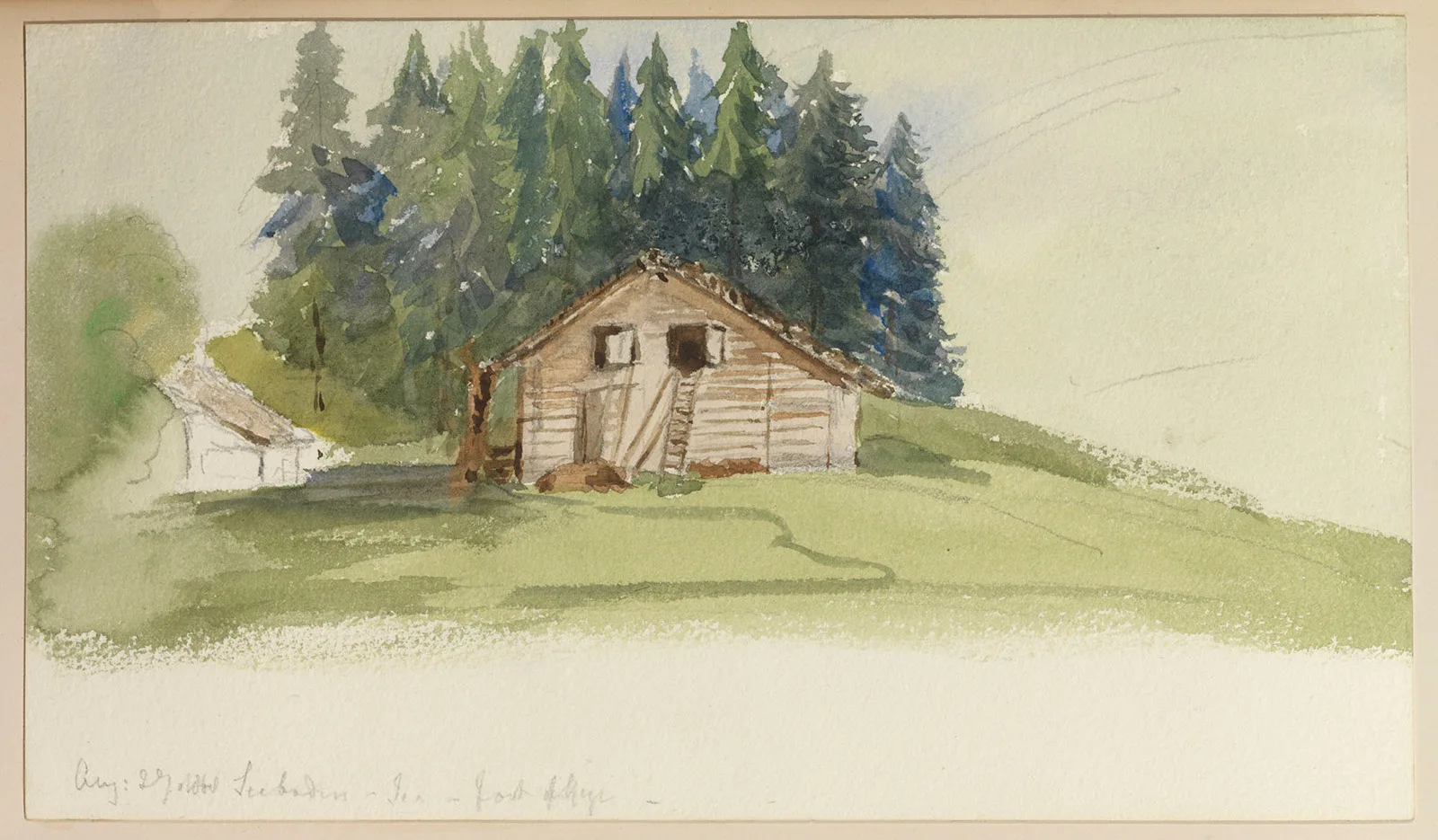

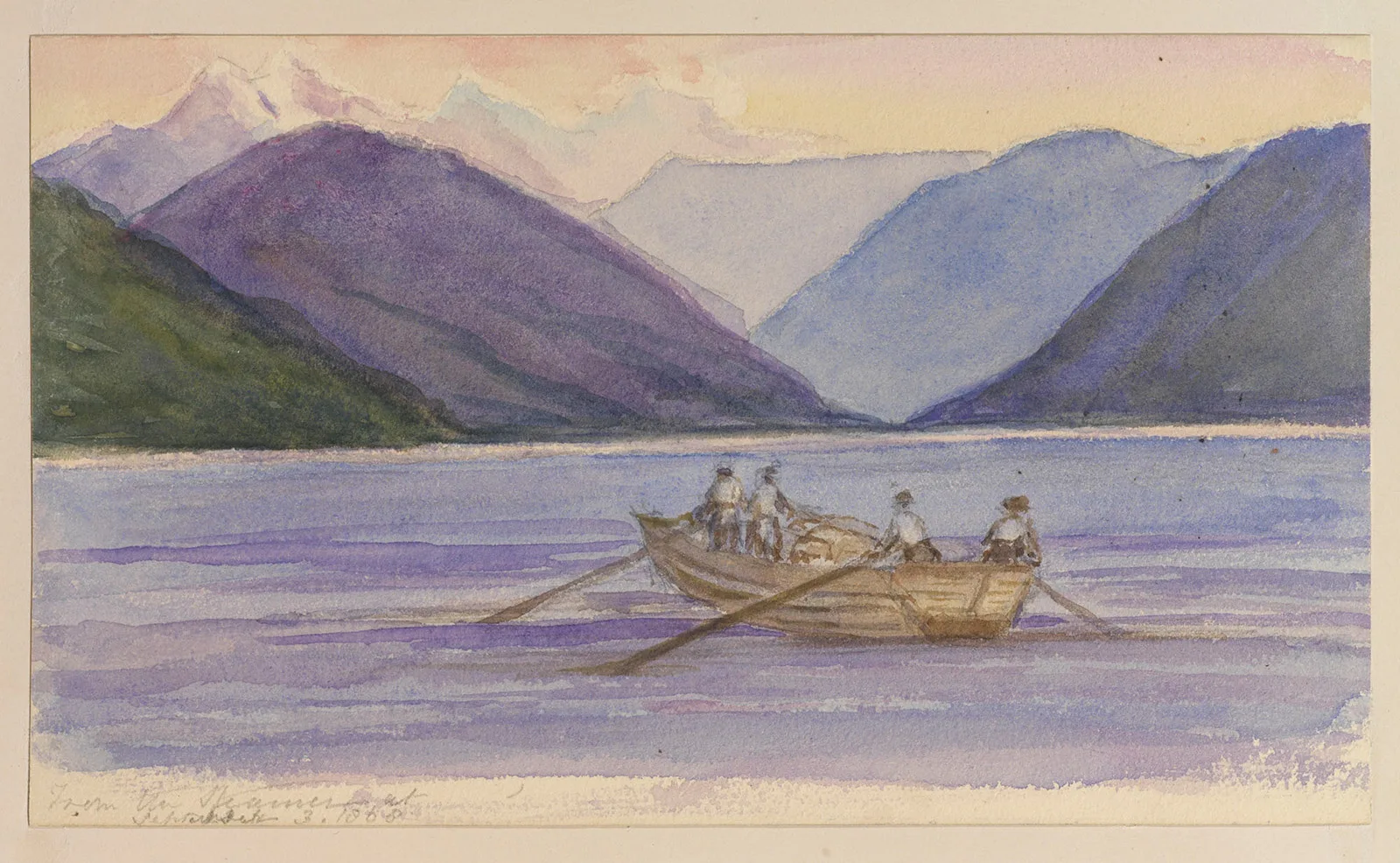

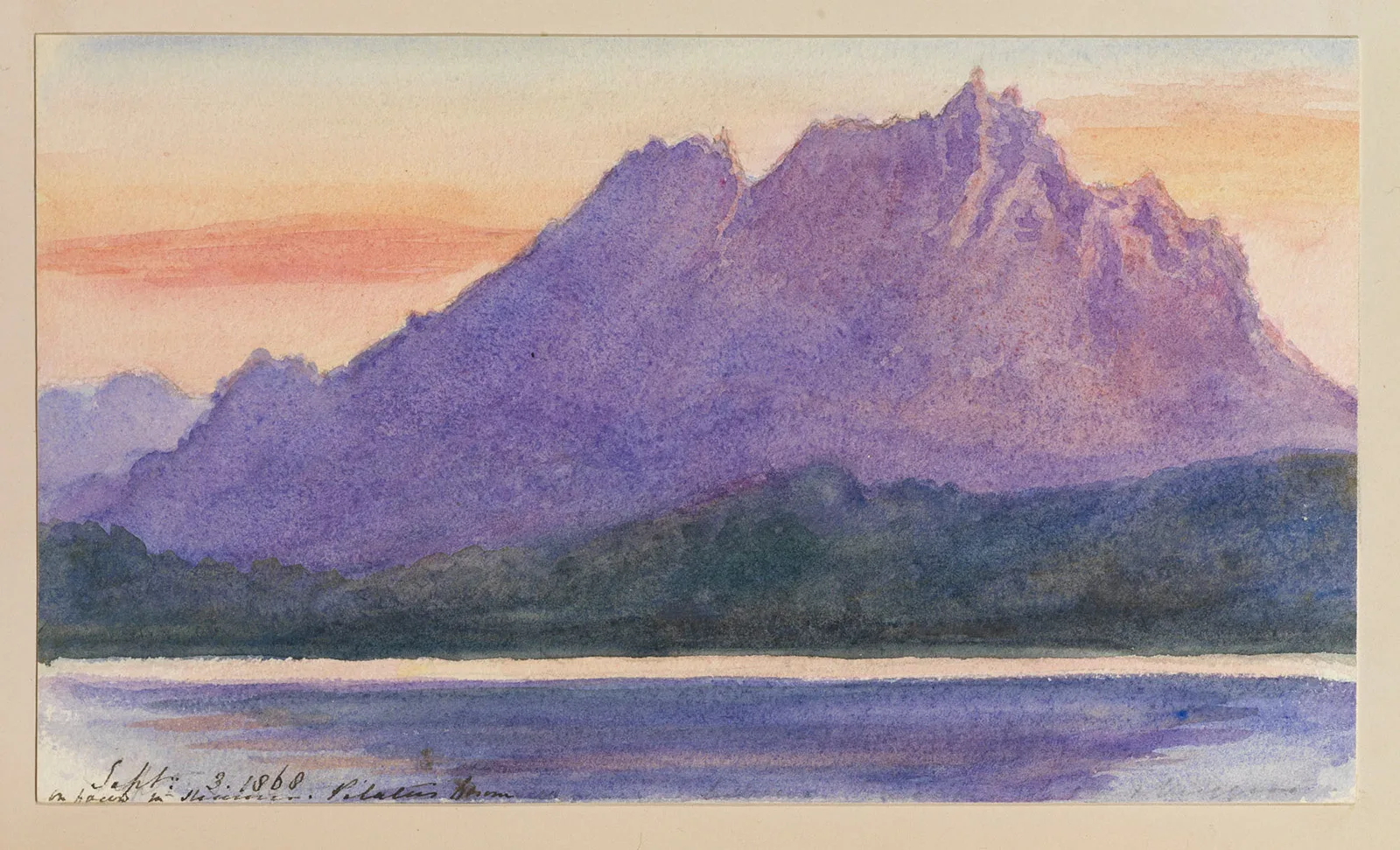

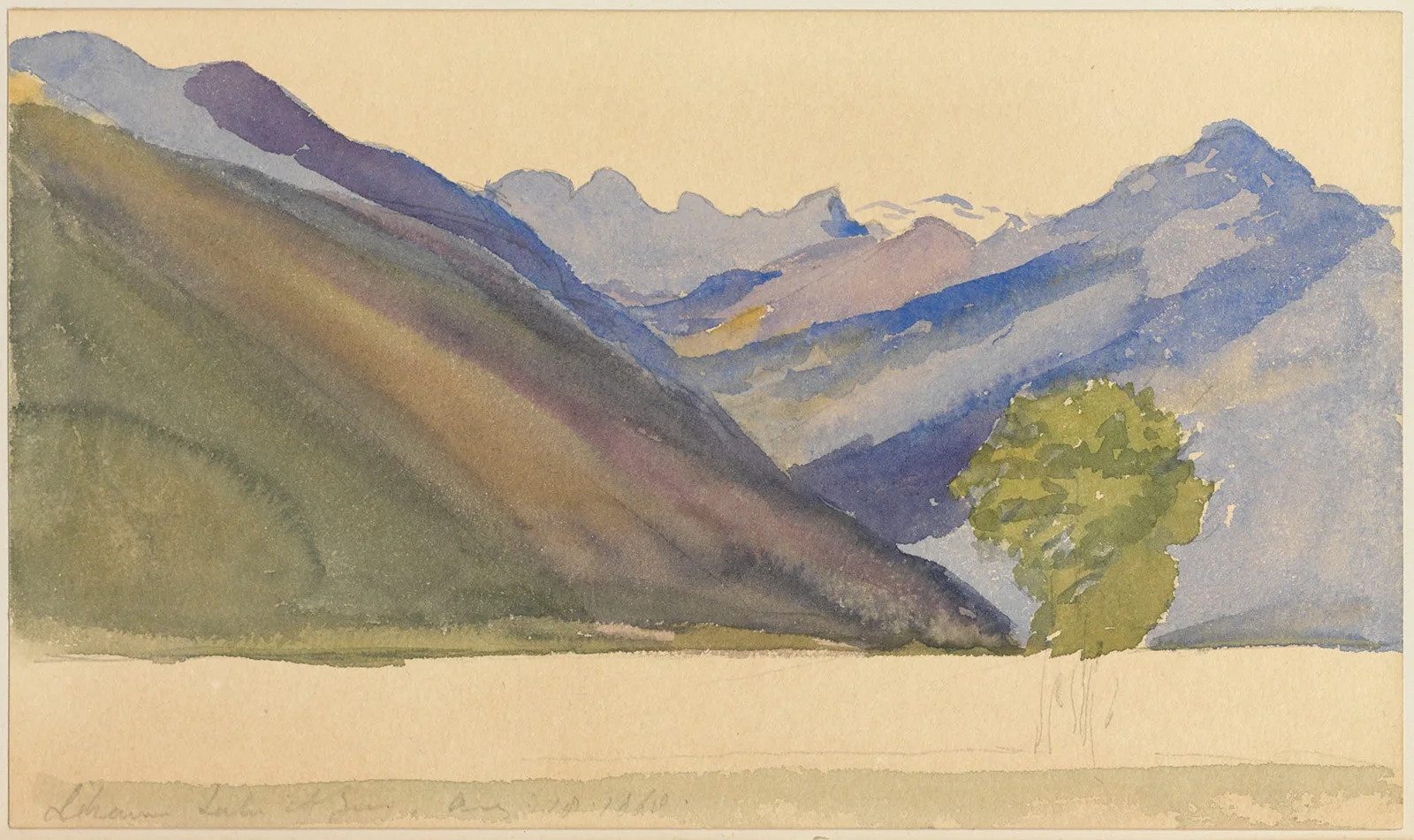

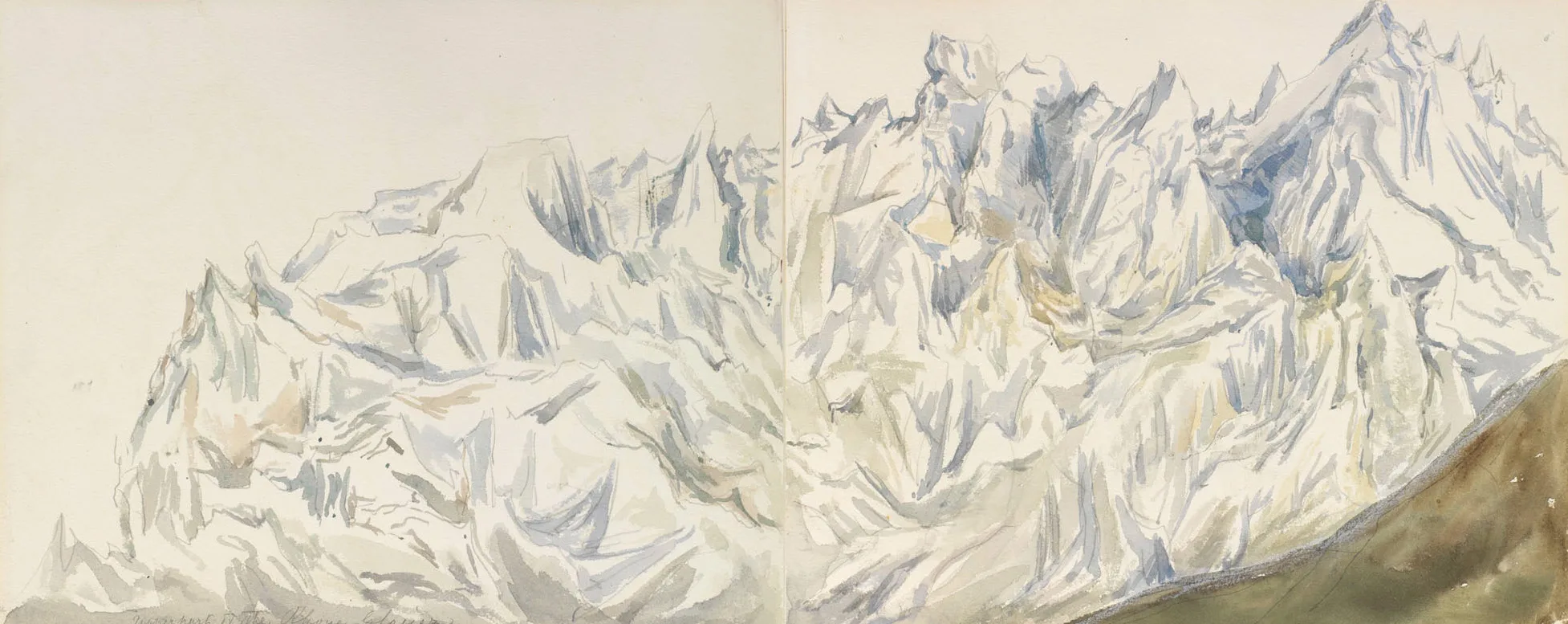

In her day, Queen Victoria was the most powerful woman in the world. She came to Switzerland in 1868 to rest and recuperate, and made numerous sketches and paintings of the Swiss scenery. Many of these watercolours and drawings survive today.

The view … out over the lake with the city spread out before it, surrounded by the most magnificent mountains & vibrant greenery in the foreground, is ideal. It is truly what I dreamed of, but I could hardly believe I was now seeing it with my own eyes!

She never once missed afternoon tea…

…or went anywhere without an easel

Visiting Royals – From Sisi to Queen Elizabeth

Although Switzerland has no royal tradition, royal families have long held a certain fascination for the Swiss. All royal visits, whether by an emperor, empress, king, queen, prince or princess, and for whatever reason, whether politics, business or personal, had one thing in common: they triggered – both then and now – immense excitement and fascination among the Swiss public. The exhibition demonstrates this through many pictures and exclusive possessions of these bluebloods.