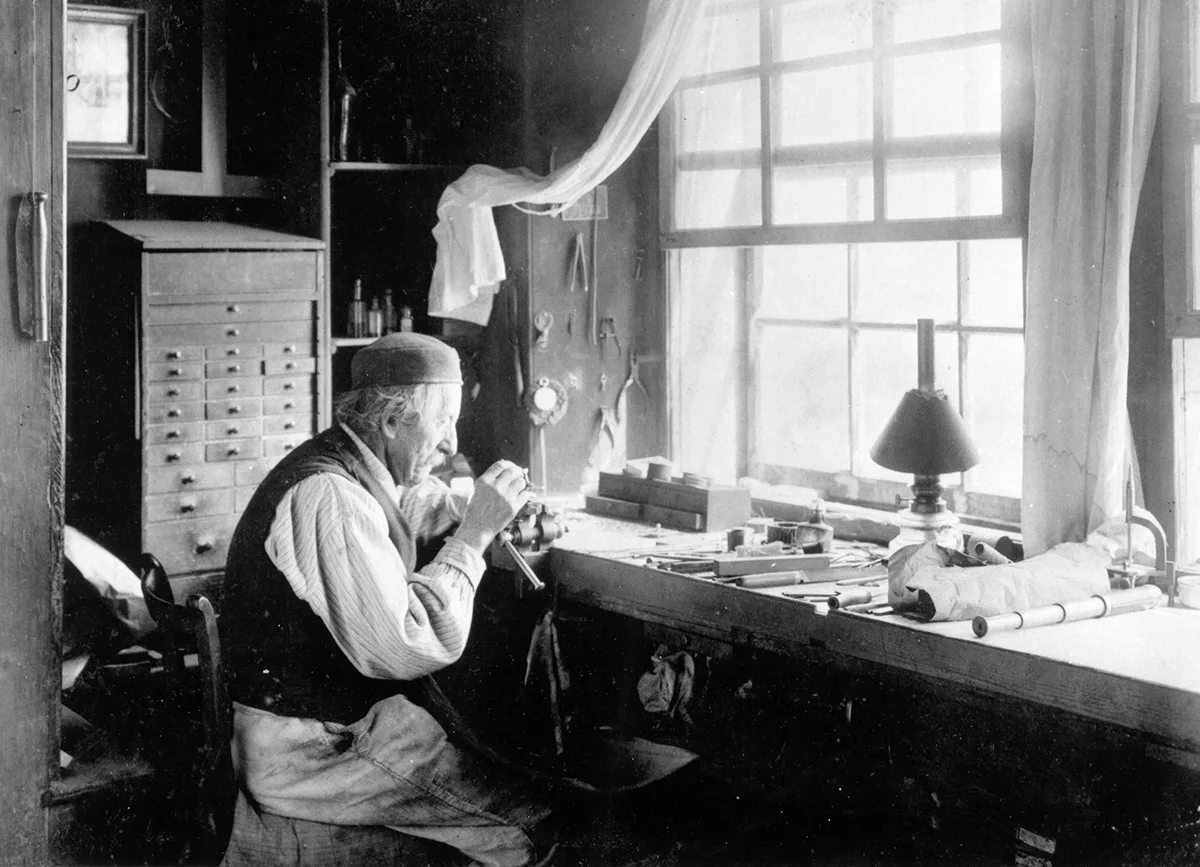

A watchmaker: portrait of a bygone era

Edouard Kaiser of La Chaux-de-Fonds was from a watchmaking family and dedicated a part of his artwork to the trade, which was in upheaval at the time.

Comparing the two artworks reveals a fundamental shift in focus. While de la Tour concentrated on creating a mystical atmosphere, Kaiser was more interested in meticulously portraying the nature of the work. Our attention is drawn to this dignified, old craftsman, regardless of what the beholder may or may not know about the more technical aspects of watchmaking. Is the old man filing, adding a hallmark, or maybe engraving?

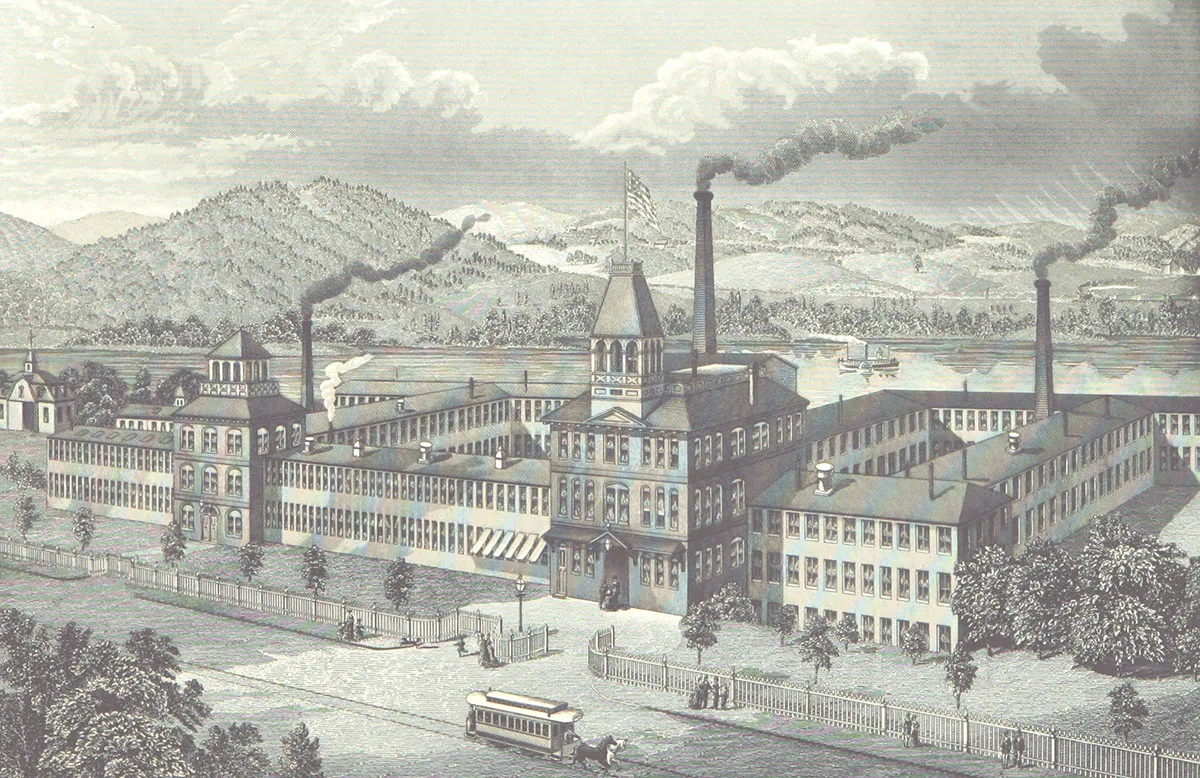

Watchmaking, having begun as a sideline for poor farmers in the Jura region looking to supplement their meagre income by working from home, was steadily shifting towards a quasi-industrial manufacturing base. The resulting deterioration in working conditions and growing pressure through piecework finally led to workers’ uprisings.

‘Atelier de boîtiers’ was a great success at the 1900 Paris Exposition and won a silver medal at the international art exhibition. It even featured in the official exhibition catalogue, an honour that bypassed the exhibited (albeit not prize-winning) works of Ferdinand Hodler and Cuno Amiet.

The photographers of the day had fewer inhibitions. In some respects, uncompromisingly true-to-life paintings like the Vieil Horloger could be seen as competing with photography.

Kaiser’s transfer of a photograph to a different medium was for the benefit of his clients: bourgeois circles who saw painting as having more cachet than photography. Photographic works were exhibited alongside other craftwork as opposed to being part of the art exhibition at the Paris Exposition in 1900.