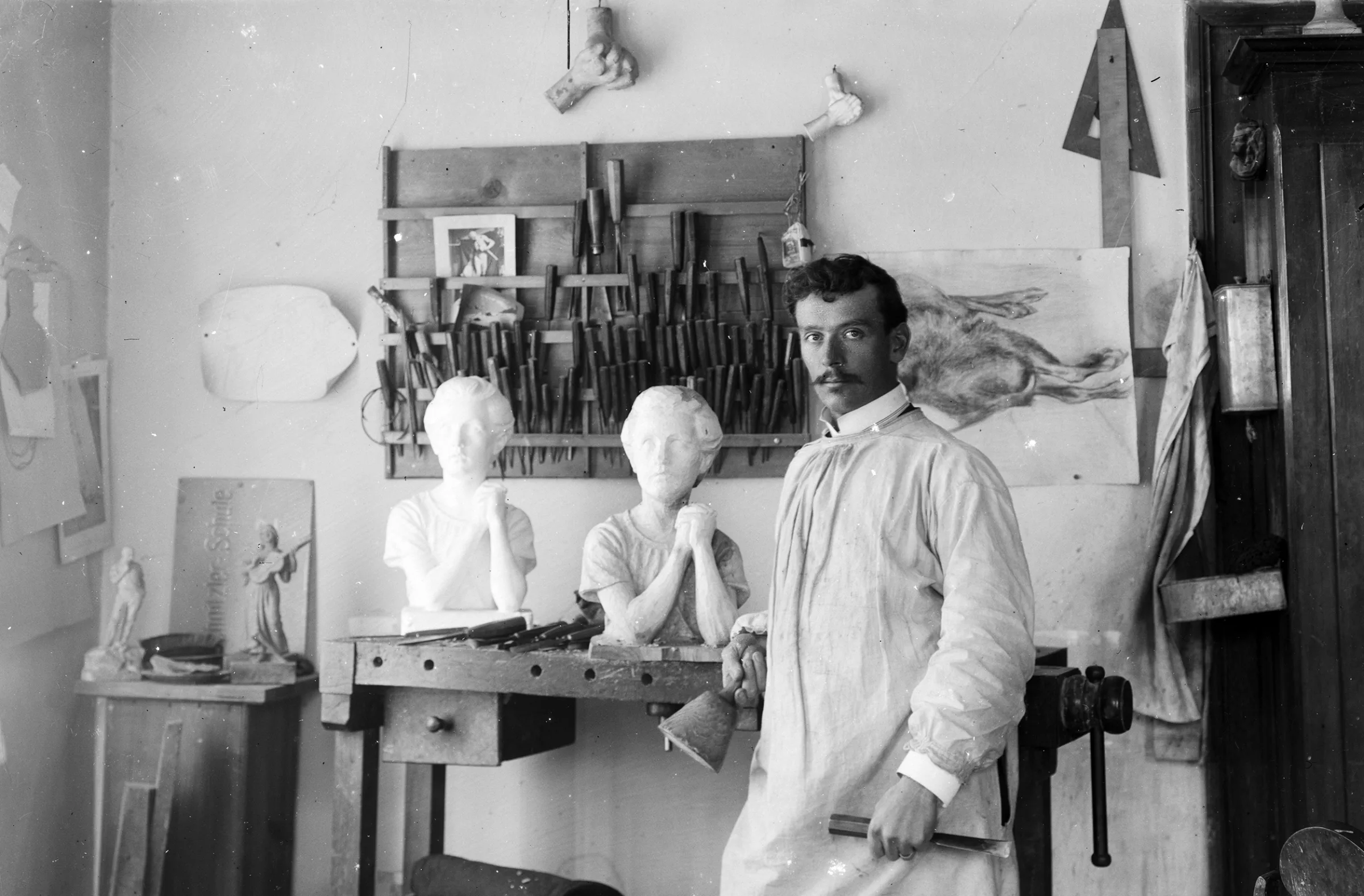

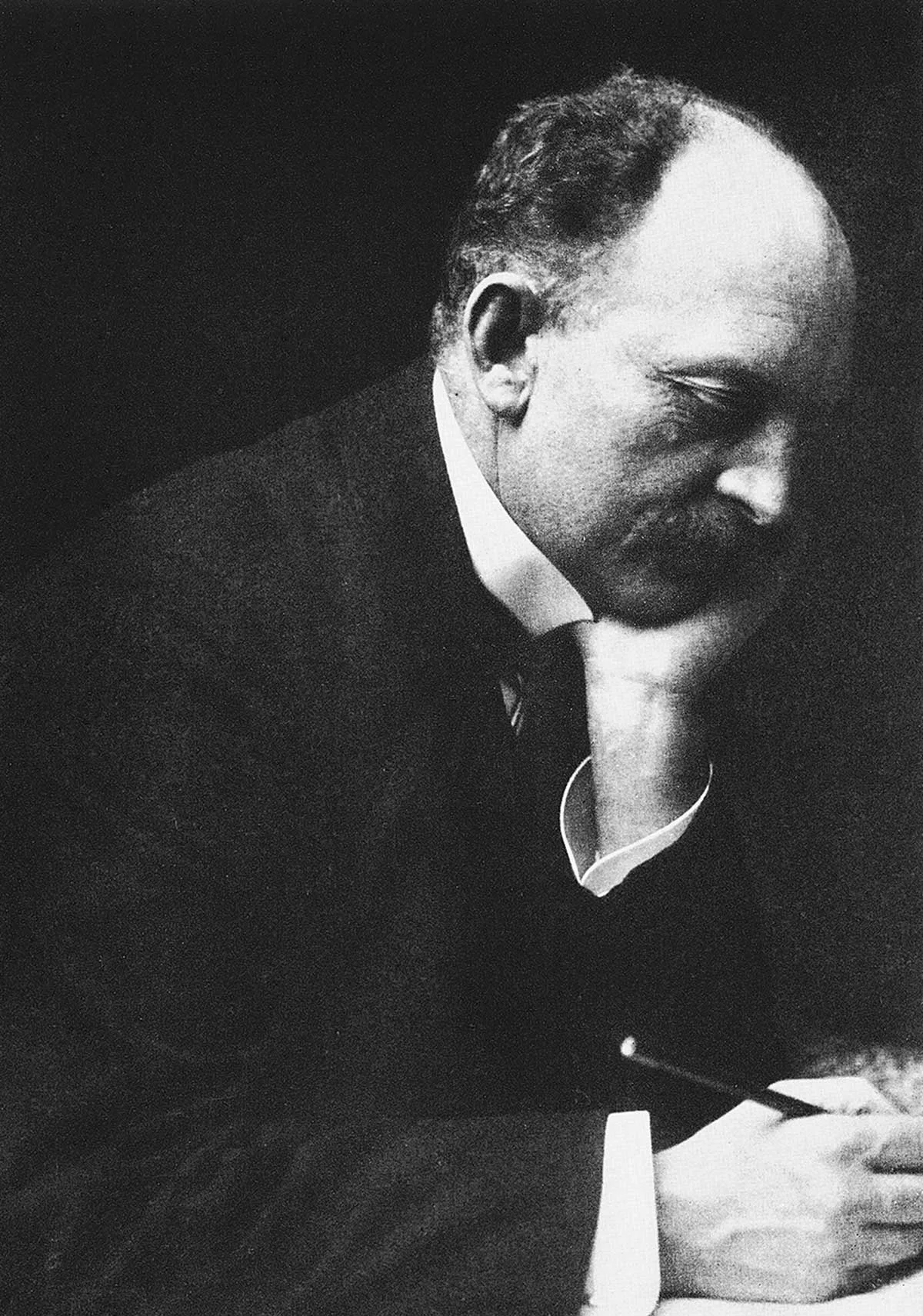

The man who gave the mountains a face

Emil Nolde had a life-long fascination with the Swiss Alps, immortalising his love of the mountains in many humorous works.

Not cut out for teaching

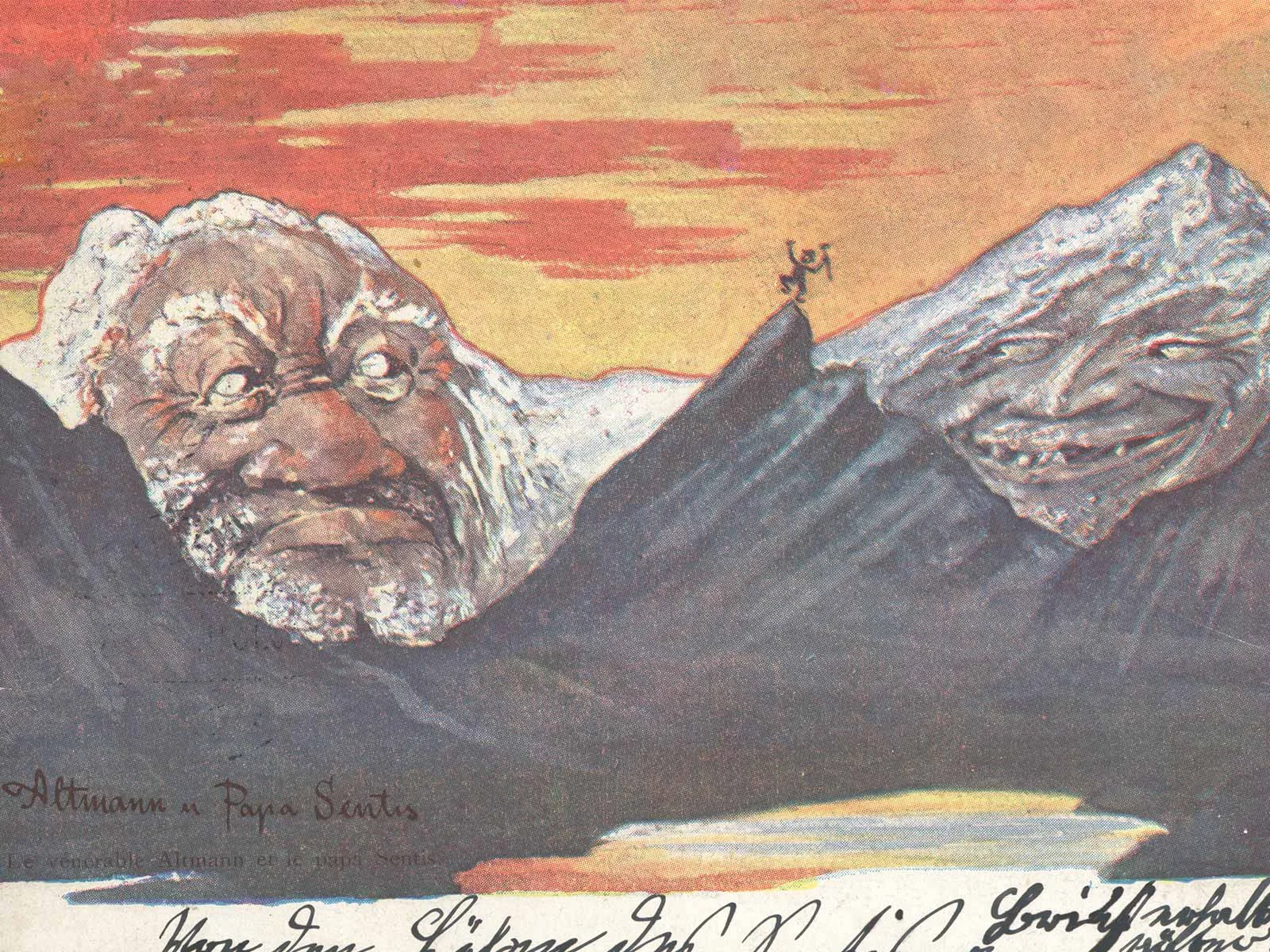

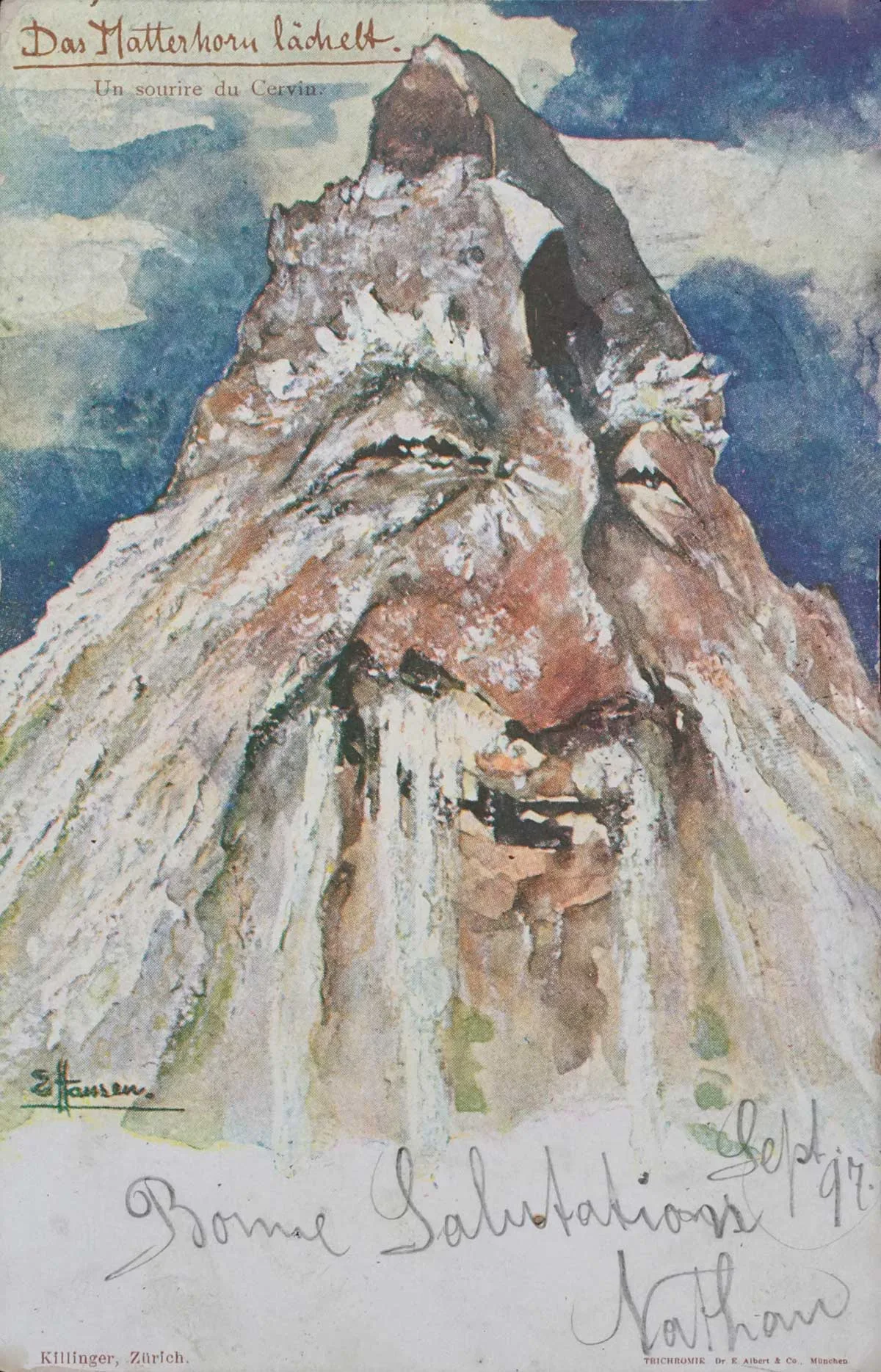

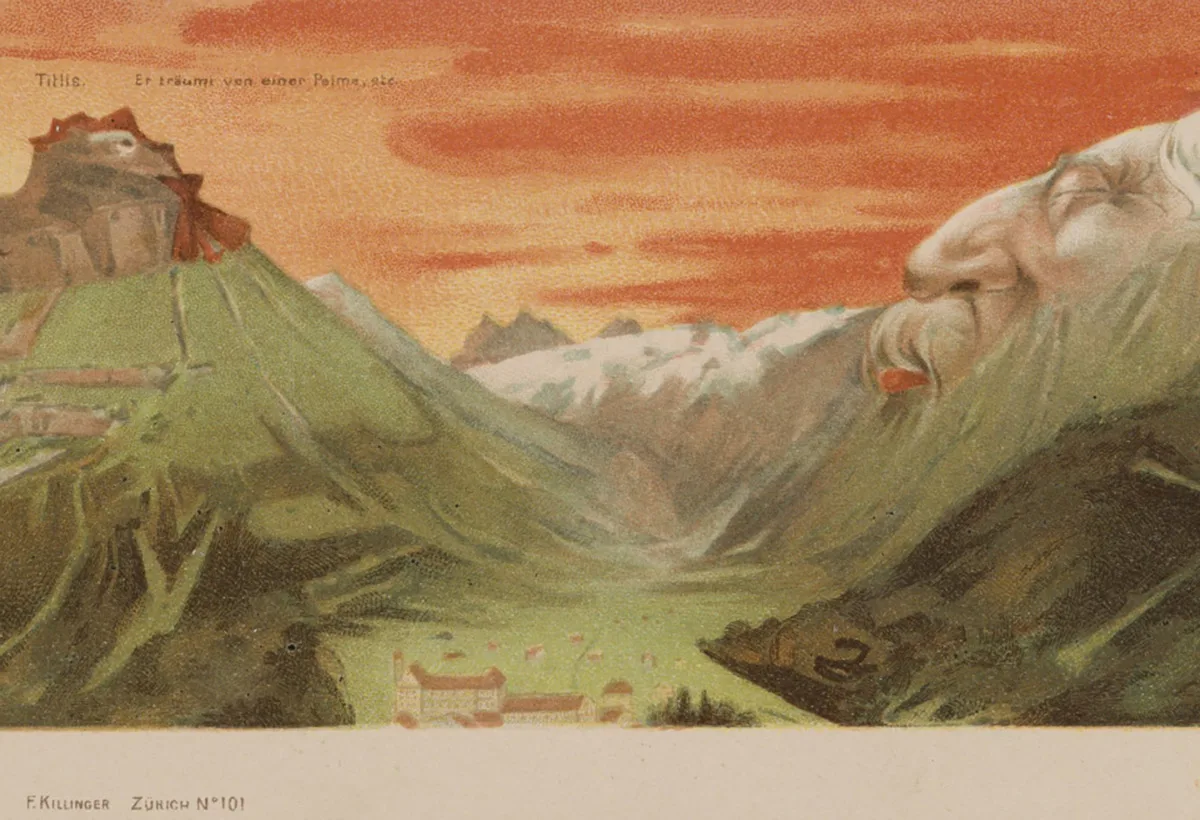

Nolde's mountain faces were inspirational and were copied by numerous contemporaries, as these two postcards show. Swiss National Museum