The pursuit of precision in timekeeping

The Swiss Post was long responsible for bringing the exact time into households in Switzerland, whether by phone or by radio. Sometimes it also offered a morning wake-up call.

As mechanical clocks became more precise, a quantitative notion of time arose, challenging people’s intuitive ‘sense’ of time’s passing. However, the introduction of measured time was a slow process and different time systems long co-existed. The Church and the clergy saw the relentless pursuit of precision timekeeping as competition, which threatened to erode their control over people’s daily rhythms as the day was no longer punctuated by religious rituals. The decades after the French Revolution saw the Church repeatedly attempt to hold back progress and retain its control over people’s time – but by the mid-19th century this was clearly a losing battle.

Railways and telegraphs

The international community was experiencing similar problems and everyone needed to be on the same page for the increasingly globalised world to run like clockwork. The International Meridian Conference held in Washington D.C. in 1884 fixed the prime meridian in Greenwich, paving the way for the global introduction of standard time zones. The Federal Council subsequently introduced Central European Time in 1894 and the whole of Switzerland was aligned under a standardised system of timekeeping.

Neuchâtel as Switzerland’s timekeeper

The time signal was transmitted via telegraph line at lunchtime as demand for telegram traffic was low then. The watchmaking schools and clock factories paid a modest sum to obtain the exact time from Neuchâtel. Meanwhile, the PTT used the time signal for free and charged Neuchâtel Observatory a few hundred Swiss francs a year to use the lines – even though it was itself a beneficiary of the precise time from Neuchâtel.

00.00

The talking clock. Recording from the 1950s. Swiss National Sound Archive

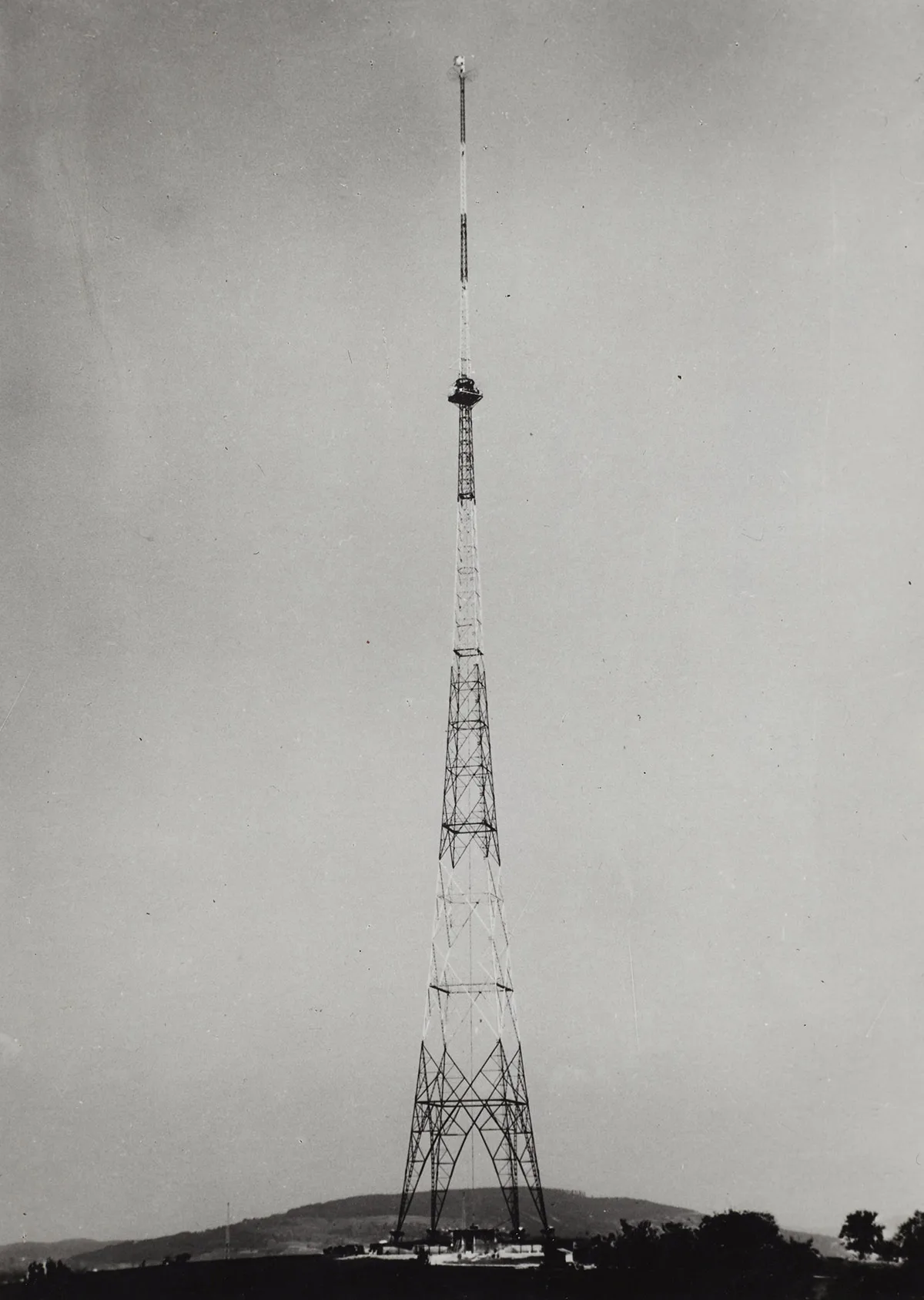

After the outbreak of the First World War, the Swiss telegraph administration seized all existing radio receivers. To replace the time signals, it introduced a telephone service in 1916 that was also based on the time signal from the Eiffel Tower. Between 10:56 and 11:00, a series of signals were transmitted over the phone.

Since 1982, the Federal Institute of Metrology has been responsible for precise time measurement in Switzerland. Meanwhile, the observatory in Neuchâtel shut down its services in 2007. When the state-run enterprise PTT was dissolved, its successors the Swiss Post and Swisscom lost control of precision timekeeping. The last radio time signal broadcast in Switzerland was on 14 December 2012 at 12:30. This is because the new DAB+ digital radio technology makes real-time transmission impossible.

This blog post was originally published on the blog of the Museum of Communication Bern.