The bombing of the Sihl plain

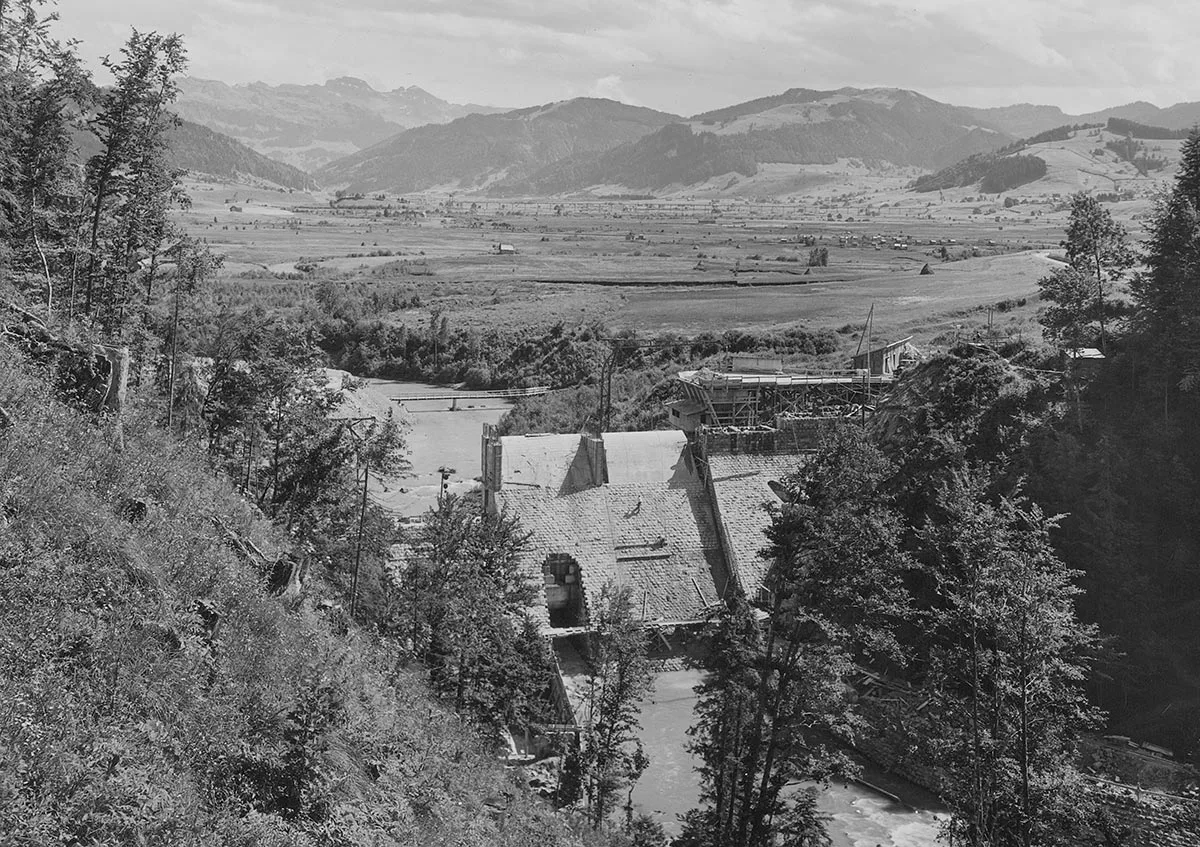

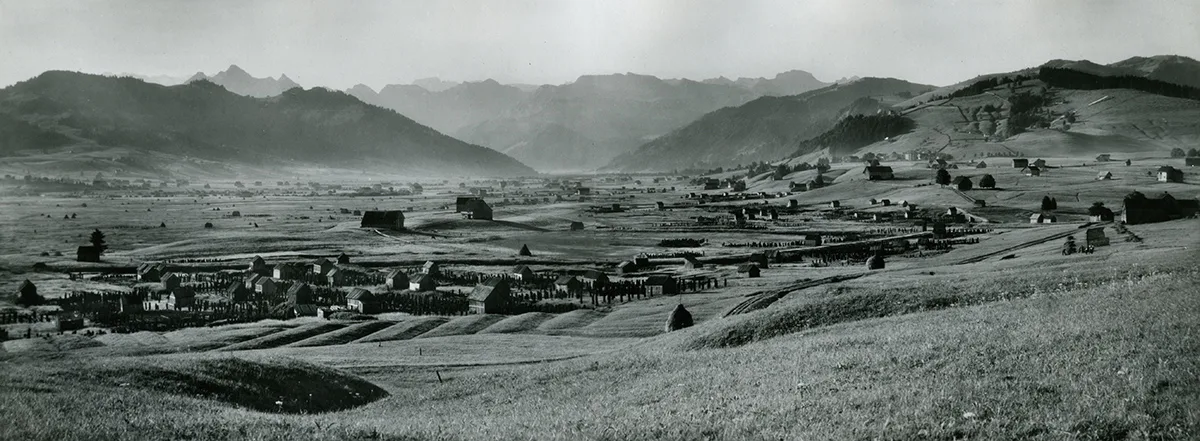

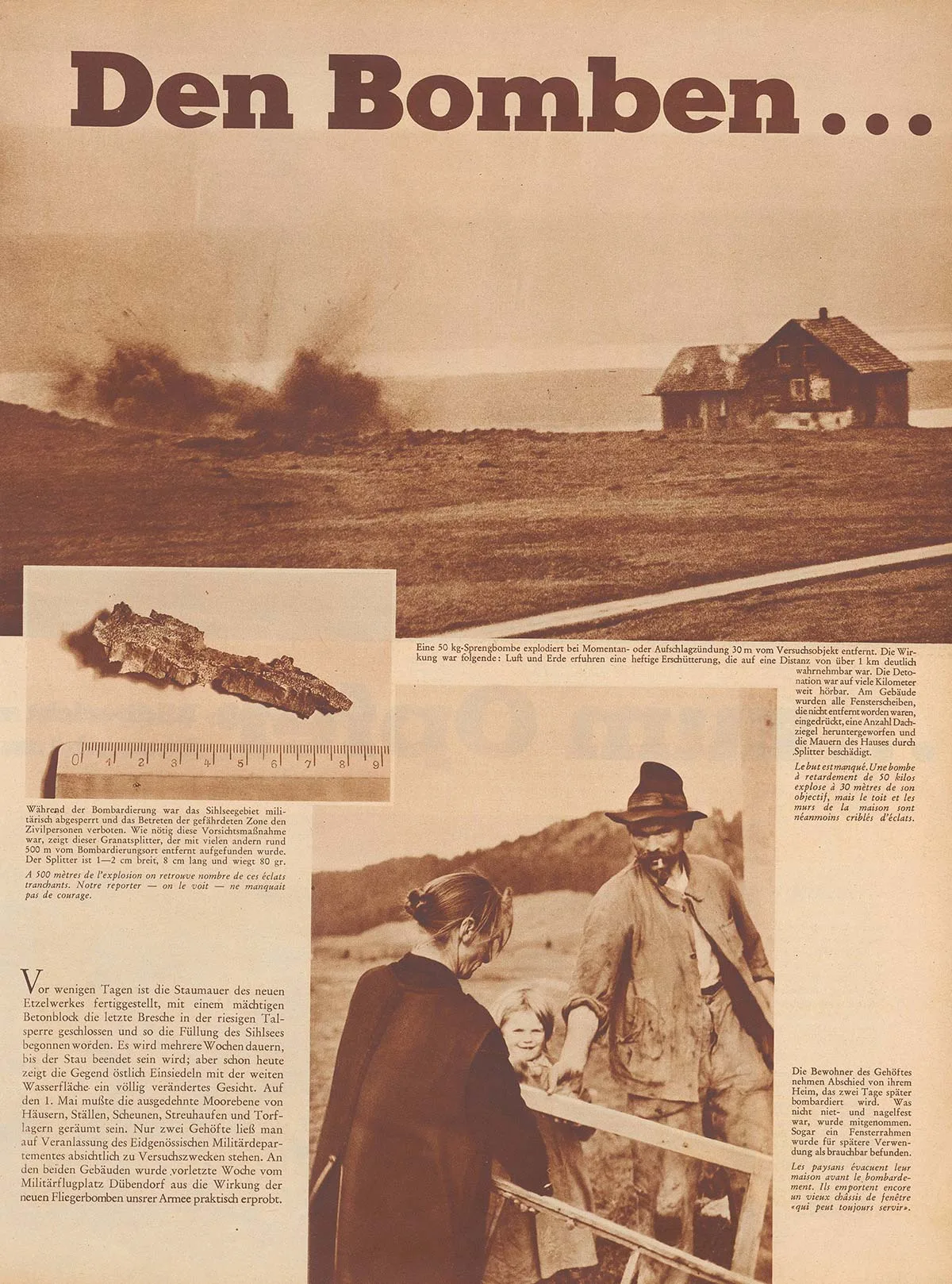

The damming up of Lake Sihl to create a reservoir started on 30 April 1937. A few days later, the Swiss air force bombed two vacated farmhouses in the area designated for the lake as part of a training exercise. The media interest was huge. Hundreds of people who had been evacuated from their homes to make way for the reservoir also followed the spectacle.

A project that fascinated the public

Waiting for the bombardment

Next up was the second house in the direction of the hamlet ‘Birchli’. The slopes were “full of spectators” by then according to a report in the Neue Zürcher Nachrichten (NZN). The people followed the dive and dropping of the bombs “with bated breath”. “Aerial bombardment in the Lake Sihl basin” was the headline in Der Sonntag magazine. The NZN concluded its report thus: “The people experienced a sensation and a rare, remorselessly destructive spectacle. Something we hope never to see for real.”

A displaced family

These days, Lake Sihl looks like it’s been there forever. No trace remains of the natural and cultivated landscape from the 1930s, which now lies almost 20 metres under the water.