Swiss picture books before 1900

Ernst Kreidolf’s Art Nouveau books, in which he brings flowers and insects to life, are among the oldest Swiss picture books. His book “Flower Fairy Tales” was published in 1898. Up until then, illustrated books for younger Swiss children were very rare.

Picture books as we know them today are usually aimed at small children, contain a large proportion of illustrations that are essential for understanding the story, and are meant for entertainment. Picture books are read together: The child looks at the pictures, the adult reads the text aloud. The concept of children’s literature as a literary genre written specifically for children and their level of experience did not emerge until the 18th century. The entertainment value of children’s literature was not a given in the historical context. For a long time, books aimed at children were used as a tool for moral, educational or religious instruction. Thus, many of the oldest Swiss children’s books include Bible stories, catechisms, primers, letter-writing guides and moral parables. Probably the best-known Swiss children’s book to date, Johanna Spyri’s “Heidi: Her Years of Wandering and Learning” (1880), stood out for its strong interest in the psychological inner life of a child, among other things. The advent of children’s literature for entertainment purposes was thus a relatively new development leading up to the 20th century, at least in Switzerland.

The production of books with a large proportion of pictures was a very technically laborious and therefore expensive process. Although many books aimed at children and young people were adorned with separate picture panels, wood engravings or etchings, the proportion of pictures was very small in relation to the total volume. It was only through new innovations in printing technology in the course of the 19th century that it became possible to print picture books in larger quantities more cheaply and – most importantly – in colour. Only middle-class households could afford the first picture books – not only because of the high price, but also for practical reasons: Most labourer and farming families presumably had little time to devote to reading a book with a toddler.

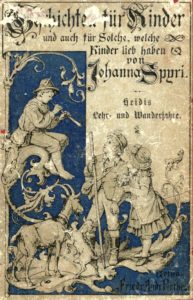

Cover of the eighth edition of Johanna Spyri’s “Heidi”, circa 1887. Source: wikimedia

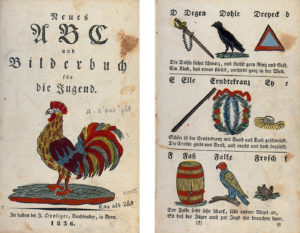

The few Swiss books preceding Ernst Kreidolf’s “Flower Fairy Tales” that most closely resemble picture books were ABC books. These were no longer used just to teach reading, but came in a variety of designs and forms. While the “Little Picture Book for Children” (Winterthur, ca. 1830) shows one picture for each upper- and lowercase letter – such as a “Dach” (roof) and a “Dohle” (jackdaw) for the letter D – the “New ABC and Picture Book for Youngsters” (Bern, 1836) also includes a rhyme to read underneath the pictures and letters. There is also a moral lesson. For example, the letter D warns: “The jackdaw is black and likes to steal rings and coins / A child who steals is a complete disgrace”.

“New ABC and Picture Book for Youngsters”, 1836. Source: University Library Bern, e-rara.ch

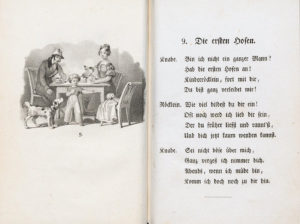

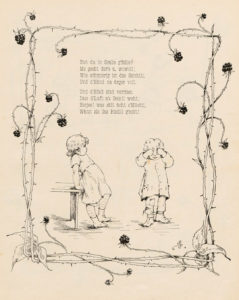

Illustrated collections of rhymes, poems, riddles and verses constitute another category of precursors to picture books as we know them today. The book “Fifty Tales and Pictures of Childhood” (1840) combines a short rhymed verse about everyday childhood on the right page, often in dialogue form, with a drawing by Heinrich Meyer on the left page, though only the first 30 poems are illustrated. The poems, which describe e.g. how reluctant a child is to take medicine or how happy a little boy is to finally be allowed to wear trousers instead of a baby gown, were written by Wilhelm Corrodi. Corrodi was a pastor in the canton of Zurich and the father of August Corrodi, who later made a name for himself as a drawing teacher and as an author of remarkably innovative children’s stories.

“50 Tales & Pictures of Childhood” by Wilhelm Corrodi, based on original drawings by Heinrich Meyer. Zurich 1840. Source: Swiss Institute for Children’s and Youth Media SIKJM, e-rara.ch

Among August Corrodi’s acquaintances in Winterthur were two women who themselves produced picture books: Sophie Schäppi, who in “Aunt Sophie’s Picture Book” (1885) lovingly illustrated Swiss-German poems by Louise Ziegler about the everyday lives of children, and the folk poet Susanne Maria Kübler, who in “Fairy Chrysalinde’s Book of Fairy Tales and Stories” (1875) created fantastic illustrations based on poems by great writers such as Goethe and Rückert. None of these early picture books achieved sufficient distribution to be considered classics today. But this soon changed: Lisa Wenger’s “Joggeli, Go Shake down the Pears” has been delighting generations of Swiss children for 110 years now – even children today, who are fortunate enough to have access to a veritable wealth of picture books.

“Fairy Chrysalinde’s Book of Fairy Tales and Stories: Whimsical Pictures for Well-Behaved Children” by Marie Susanne Kübler, Winterthur 1875. Source: SIKJM, e-rara.ch

“Aunt Sophie’s Picture Book” by Sophie Schäppi and Louise Ziegler, Winterthur 1885. Source: SIKJM, e-rara.ch

Joggeli, Pitschi, Globi… Popular Swiss Picture Books

National Museum Zurich

15.6. – 14.10.2018

Lisa Wenger’s Joggeli, who won’t shake down the pears, the kitten Pitschi, the children from the Maggi songbook or the teddy bear who sets off for Tripiti – these characters from Swiss picture books have captivated countless readers over many generations. Some Swiss artists, such as Ernst Kreidolf, Felix Hoffmann and Hans Fischer, have also become famous beyond Switzerland’s borders thanks to their illustrations. This family exhibition at the National Museum Zurich lets children immerse themselves in picture-book worlds and experience them through play. Adults encounter their once favourite characters in a cultural context. The exhibition is accompanied by a whole range of fringe activities to suit all the family.