Does Switzerland really date back to 1291? A fresh look at the country’s origins

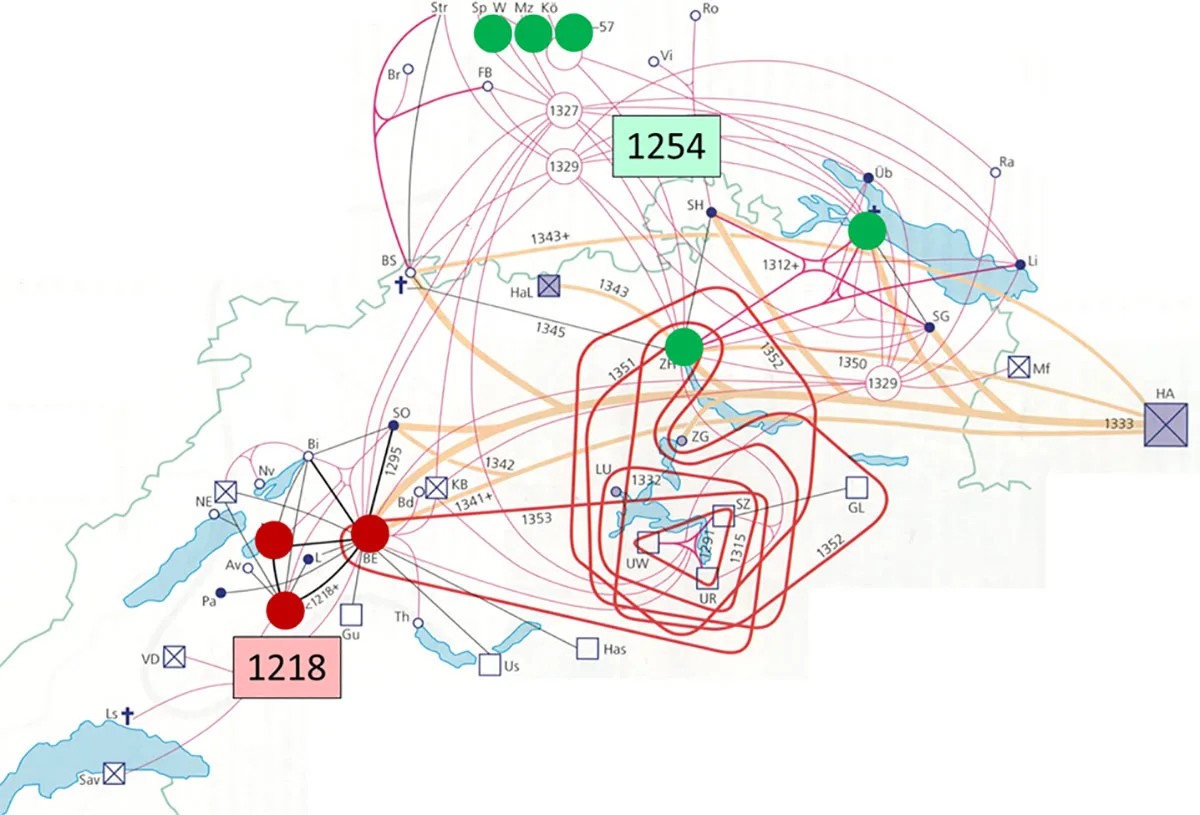

Young nations need long histories. In 1891, the Federal Council of Switzerland, a 43-year-old state at the time, somewhat arbitrarily decided the country went back 600 years, even assigning its foundation to a specific day, 1 August. Without delving too much into the dogma, the story goes something like this.

How a dead cow proved instrumental to the birth of the Confederacy

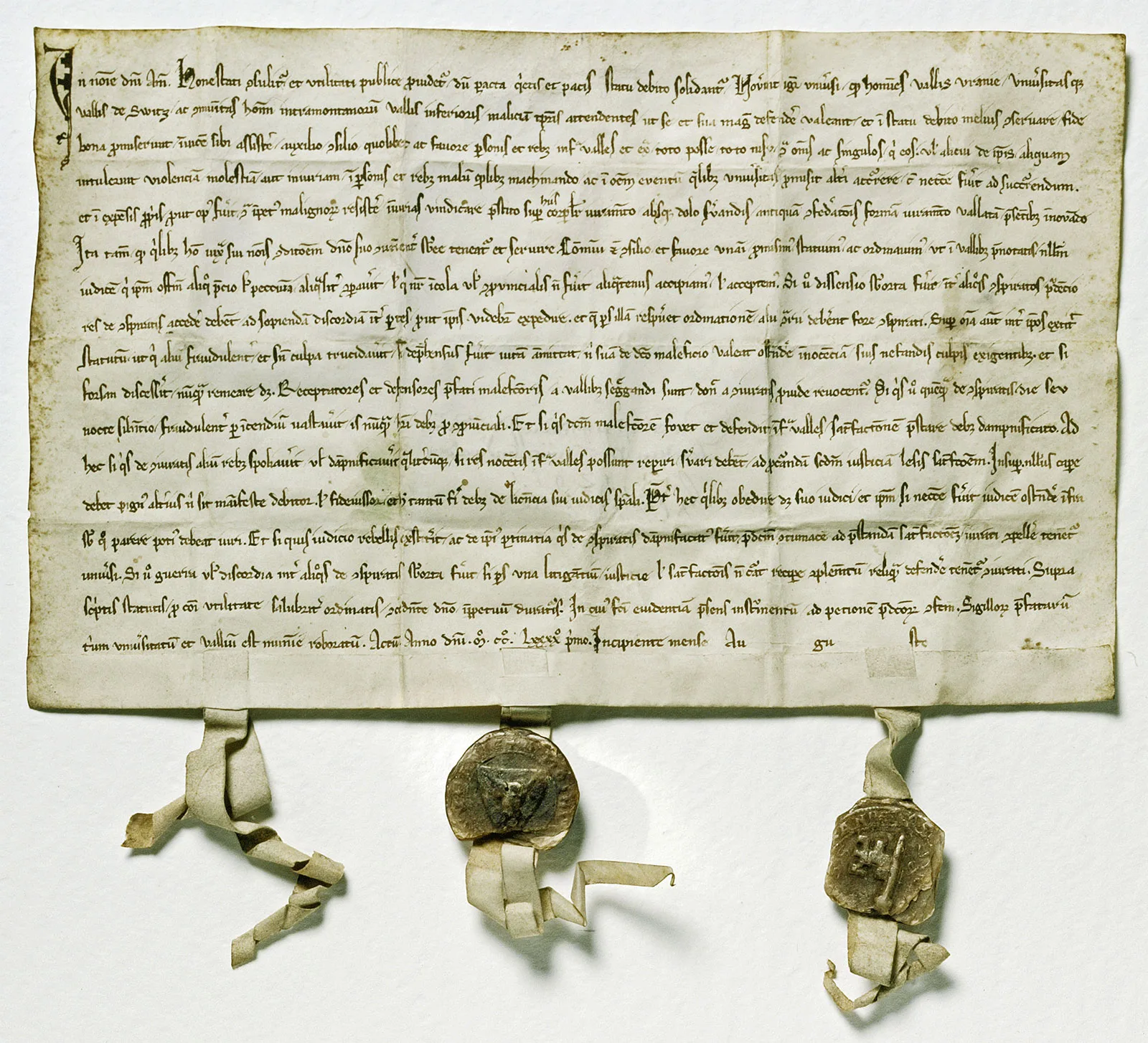

The content and omissions of the 1291 peace document

Every man shall continue to serve his overlord to the best of his abilities.

1291 or 1309? Does it really matter?

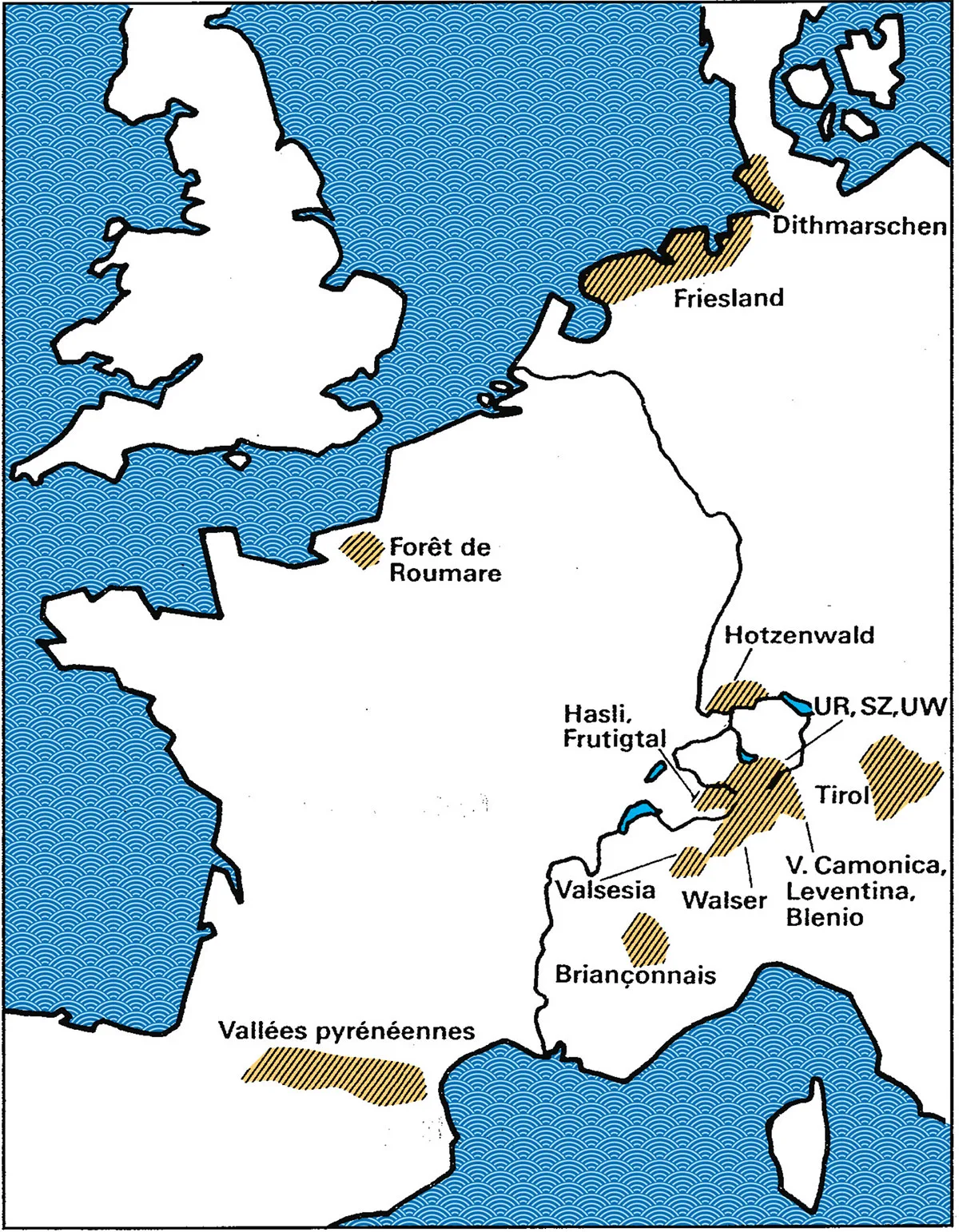

Not the exception but the norm

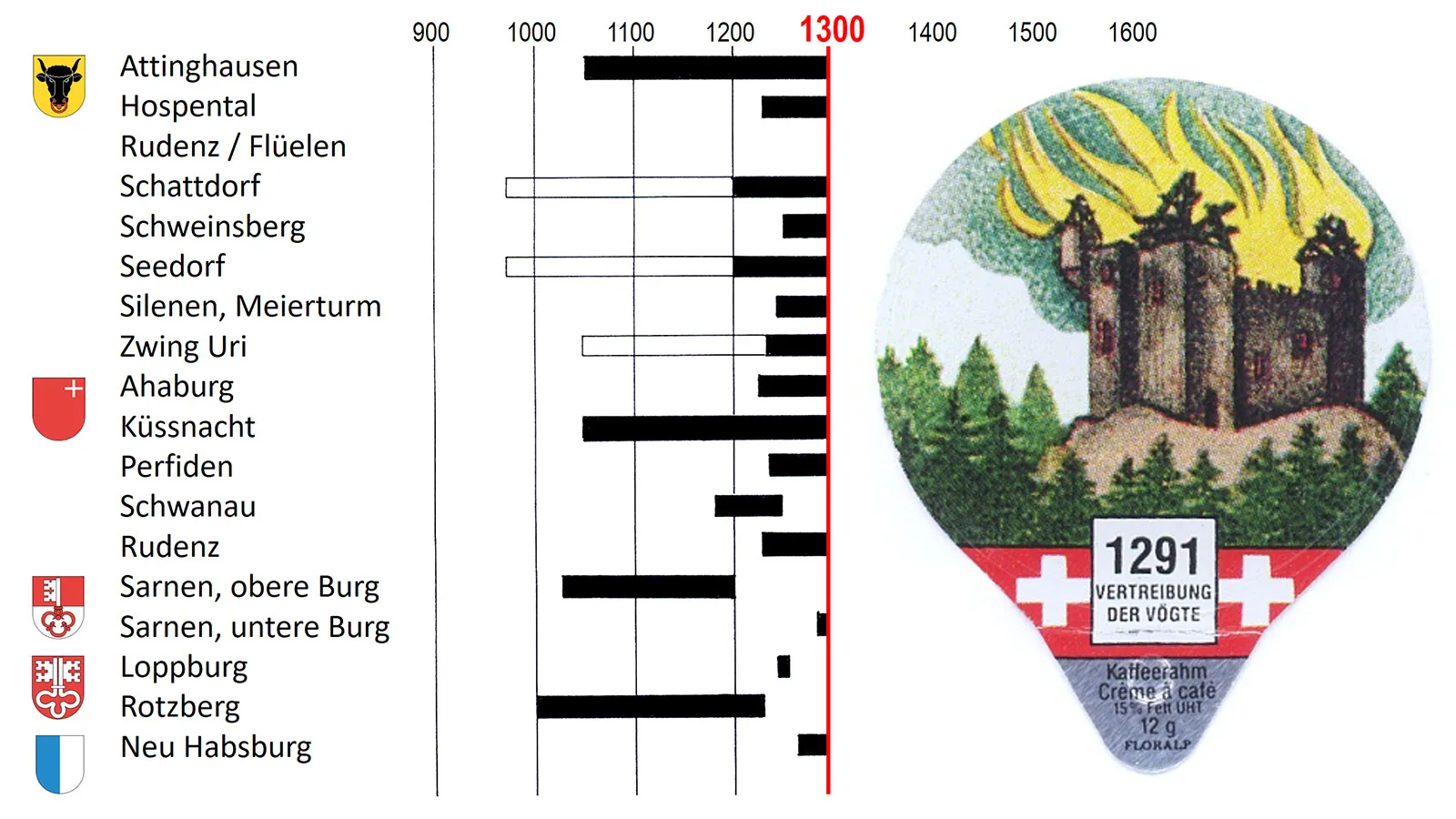

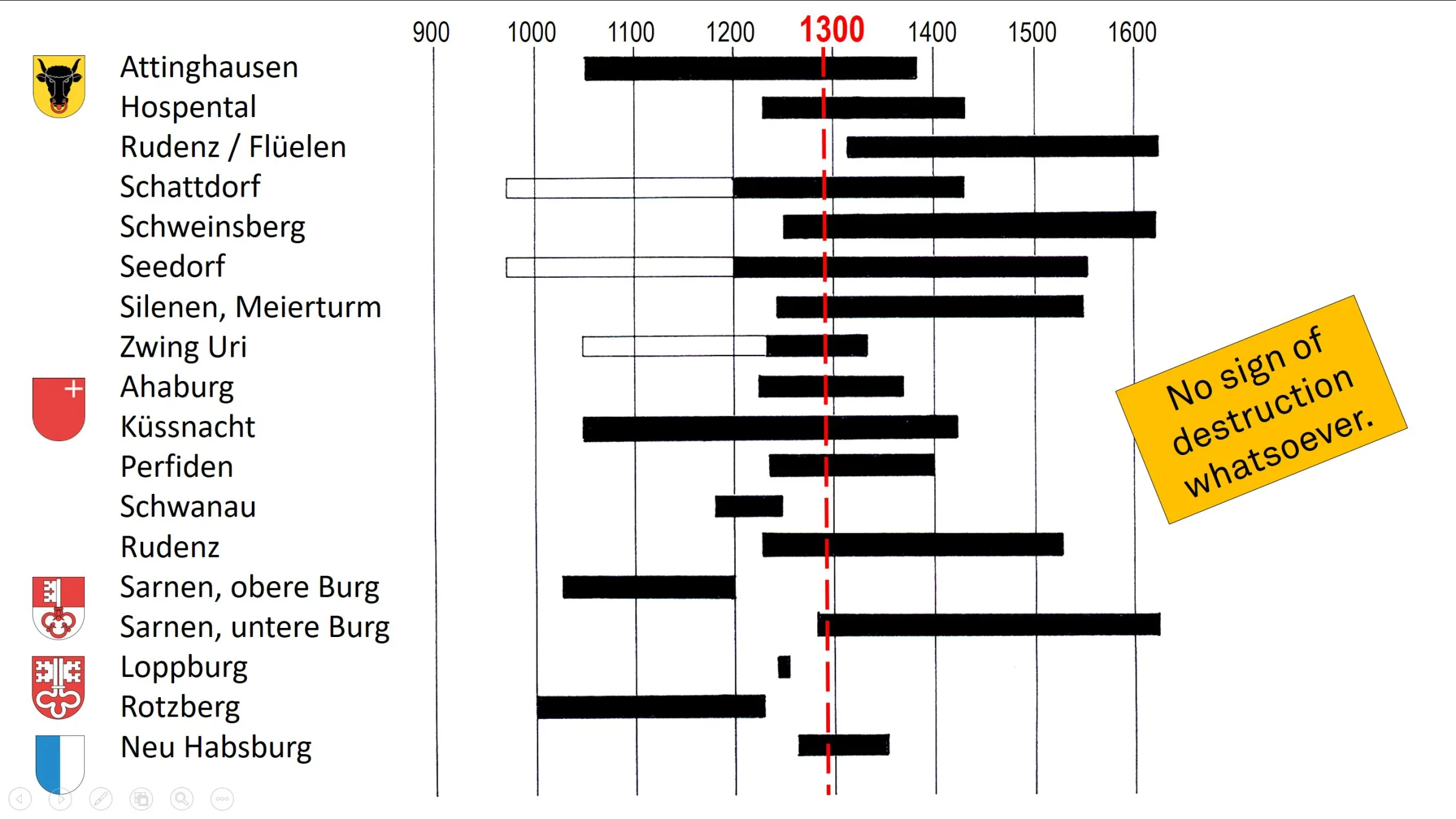

Slighting of castles. Milk portion covers vs archaeology

Of limited historical significance – instrumental in establishing a community

Alternatives to 1291?

22 December 1481 – emergence of the Confederacy

12 April 1798 – first state, first constitution

12 September 1848 – founding of the federal state

Perspectives