Illustration by Alexander Frank Lydon, 1865

The many lives of Robinson Crusoe

In 1719, Daniel Defoe published Robinson Crusoe, the most successful adventure novel in literary history: the story of the shipwreck survivor stranded on a remote island inspired scores of other ‘robinsonades’.

1659, somewhere in the South Atlantic. On a stormy night, a ship runs aground. Robinson Crusoe is the only one of the ship’s crew to survive, and finds himself on a deserted island. After a period of despair, the castaway starts to explore the island, salvages tools, gunpowder and a Bible from the shipwreck and builds himself a hut. As his hopes of rescue fade, he decides to enlarge his dwelling; he hunts and domesticates animals and even bakes bread. Later, he saves a native from the cooking pot, and from then on he has a companion. After many years, the two are finally saved, and Robinson finds waiting for him in his homeland a bank account swollen by interest payments.

Robinson Crusoe by means of a raft saves many useful articles from the ship.

Illustration by Alexander Frank Lydon, 1865

Robinson Crusoe erects a post on the shore.

Illustration by Alexander Frank Lydon, 1865

Even those who haven’t read Daniel Defoe’s text know Robinson’s story. The novel was published in 1719 with the somewhat cumbersome title ‘The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner: Who lived Eight and Twenty Years, all alone in an un-inhabited Island on the Coast of America, near the Mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, wherein all the Men perished but himself. With An Account how he was at last as strangely deliver'd by Pyrates. Written by Himself’. The book was a resounding success. The story reads like a true account of a journey, but it is fictitious. This was new and unusual at the time. Just as remarkable was the middle-class, first-person narrator, with whom broad swathes of the population could identify. Furthermore, the original version was not by any means aimed solely at children; it was only through subsequent reissues and abridged editions that the story became a novel for younger readers.

Robinson Crusoe at dinner with his little family.

Illustration by Alexander Frank Lydon, 1865

Robinson Crusoe rescuing Friday from the savages.

Illustration by Alexander Frank Lydon, 1865

Literary critics have analysed and examined the novel from every possible angle: among other things, it’s a blueprint for economic theories, psychoanalysis and criticism of colonialism. There is also undeniably a religious leitmotif. Defoe’s original version of 1719 reads like a Puritan manifesto. Crusoe’s taking off overseas is in disobedience of his father, who had wished him to pursue a middle-class career as a lawyer. The shipwreck is a punishment from God, and his salvation on the remote island Robinson’s chance to cleanse his soul and fulfil his Providence. Crusoe survives thanks to his work ethic and discipline. After studying the Bible intensively, he develops a puritanical belief that he has been ‘chosen’, which makes him even more convinced that his success on the island is proof that he has found favour with God. So his survival on the island is a triumph of his Protestant rationality and, in a wider sense, of Western civilisation.

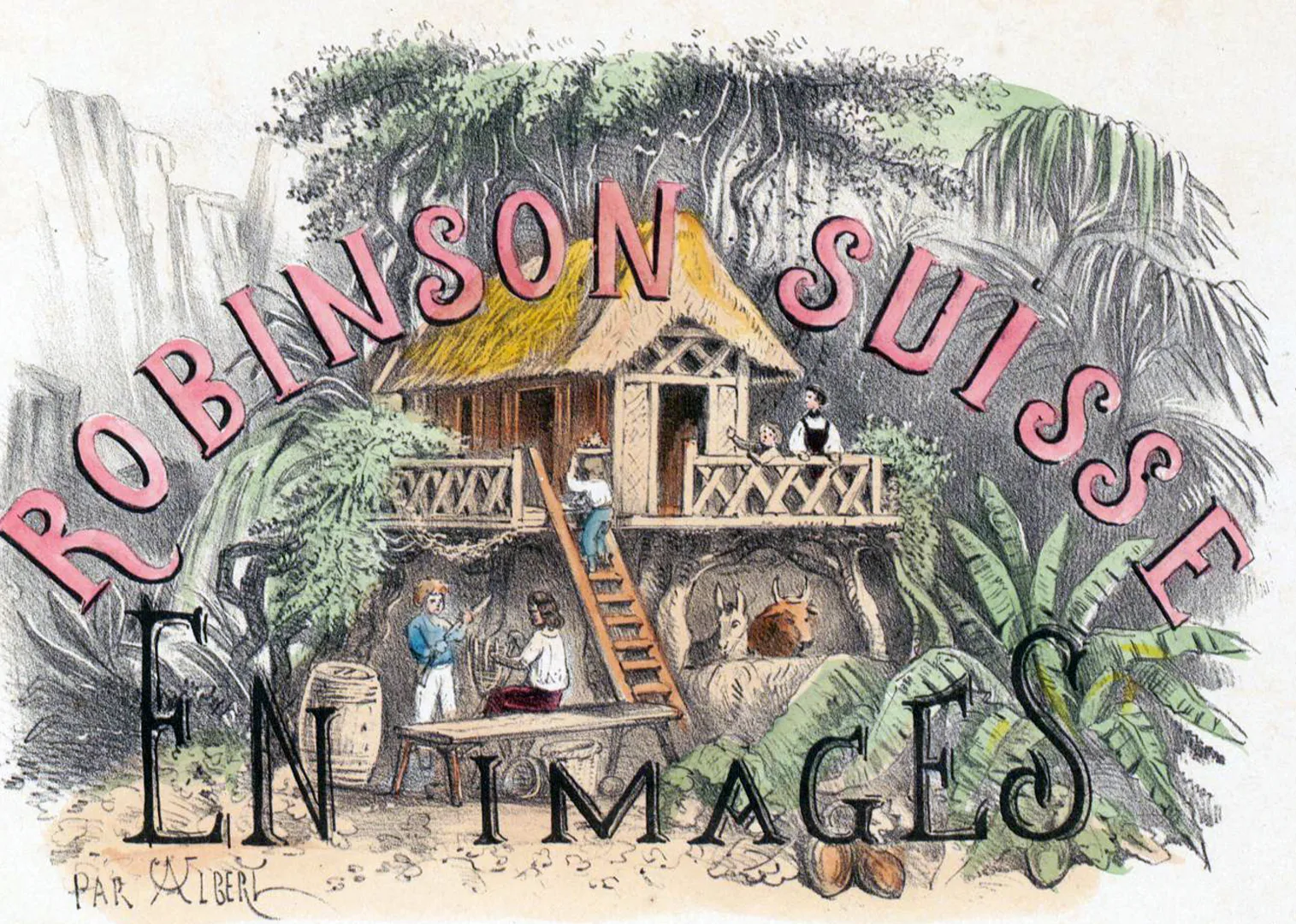

The Swiss Robinson: tame it or kill it

Within just a few years of Defoe’s text being published, translations and imitations started to appear. ‘National’ Robinsons emerged in Germany, France, Sweden, Holland… even Iceland and Lebanon created their own variations of the story. These works are called ‘robinsonades’, and one of the most successful is The Swiss Family Robinson, published in 1812. It was not originally intended for publication – parish priest Johann David Wyss, from Bern, read the story of the Swiss family stranded on a desert island to his sons. It was the eldest son, Johann Rudolf Wyss, who published his father’s work in several stages.

The Swiss Family Robinson’s ‘Falcon’s Nest’.

Swiss Institute for Children’s and Youth Media SIKJM, e-rara.ch

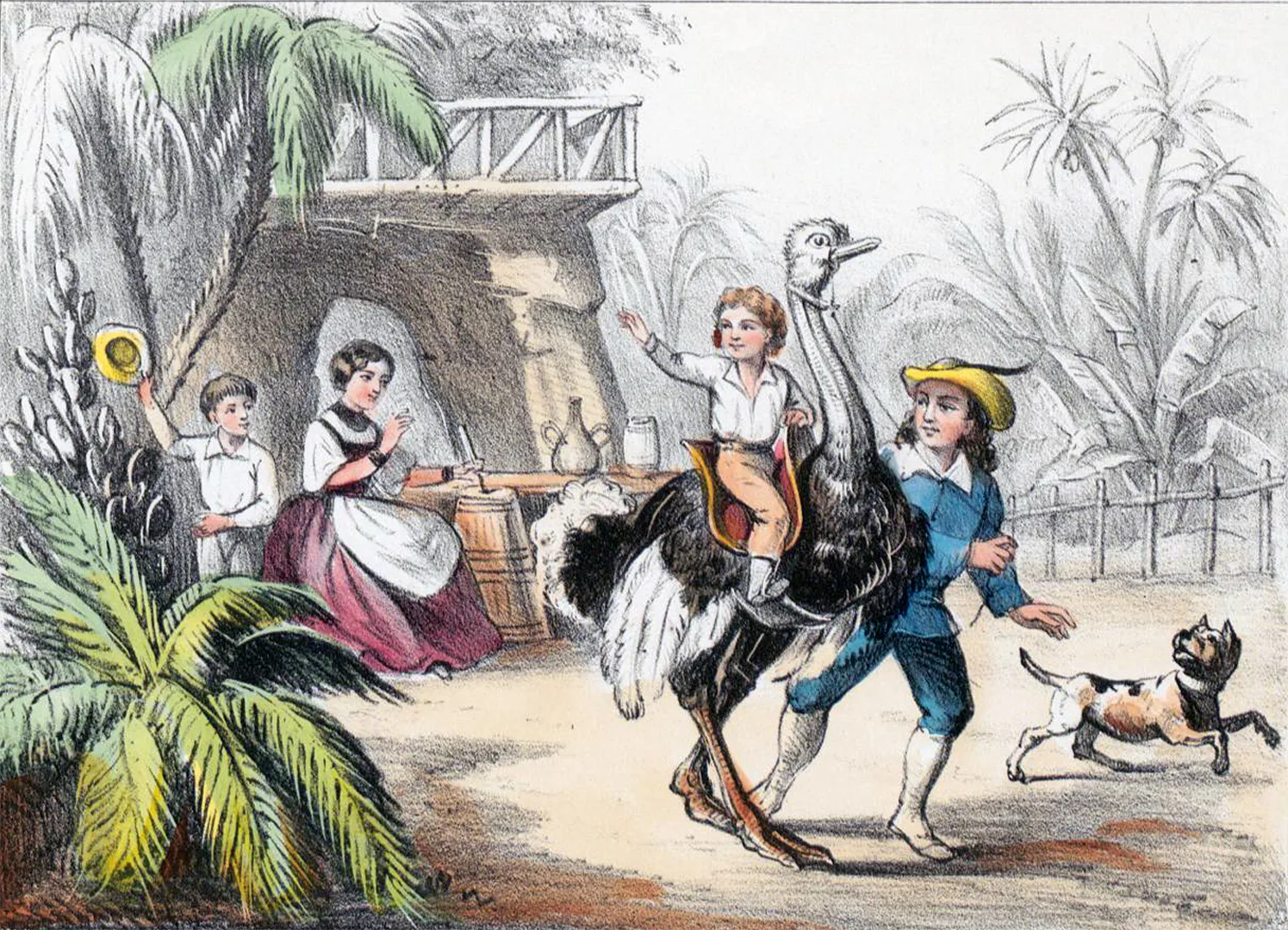

In contrast to the original, The Swiss Family Robinson was therefore a children’s book right from the start. In 1762, the educationist Jean-Jacques Rousseau recommended the novel Robinson Crusoe as a ‘textbook on the education of man through nature’. Subsequent robinsonades were strongly influenced by this seal of approval from Rousseau. Wyss’ The Swiss Family Robinson is therefore a quintessentially pedagogical work. Unlike the original, the main role is played not by an individual, but by a whole family, consisting of husband, wife, four sons and two dogs. The shipwreck is the only genuinely life-threatening moment in the story. From then on, the father teaches his sons all sorts of crafts, and the sons dutifully follow his advice. They build a treehouse, bake cassava bread, spin cotton. The family’s attitude to the natural world is also in keeping with the spirit of the times: flora and fauna must be subordinated to humans. Every living thing is judged according to its usefulness. Animals are either tamed or killed.

Little Fritz riding a tame ostrich.

Swiss Institute for Children’s and Youth Media SIKJM, e-rara.ch

The novel The Swiss family Robinson was also an international success. The first English edition was published in London as early as 1816. Like its archetype, the Swiss version also spawned numerous imitations and adaptations. Along with Heidi, it is the most famous Swiss book in the USA, thanks mainly to the 1960 Disney film adaptation. Even today, a version of the Swiss Family Robinson’s treehouse can be found at Disneyland.

→ Read in part 2 how Robinson Crusoe also had a career in Zurich.

The full text of the books

Trailer for the 1960 Disney adaptation ‘Swiss Family Robinson’.

Source: YouTube